Articulation in the Web of Transnational Social Movements

archive

Articulation in the Web of Transnational Social Movements

How can the New Global Left coalesce to once again address emergent global crises? Our research on transnational social movements and global civil society investigates the potential for a network of radical social movements to come together to play an important role in world politics in the coming decades. The histories of united and popular fronts are particularly relevant to contemporary and near-future situations. The world-systems perspective sees the evolution of global governance and the capitalist world economy as driven by a sequence of world revolutions in which local rebellions that are clustered together in time pose threats to the rule of the powers that be.

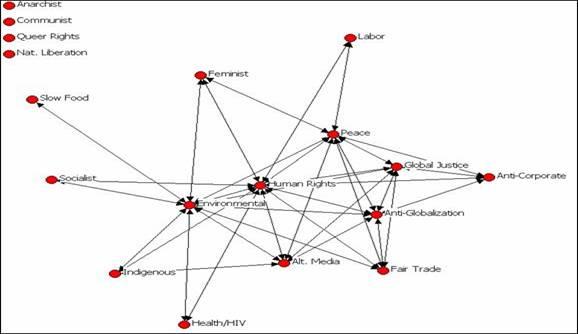

World revolutions are complicated because local and national struggles have different and often unique characteristics that reflect the various stakeholders’ interests, experiences, and perspectives. Each world revolution takes on a character of its own, and the global left is a moving target that must be constantly reassessed. The New Global Left includes old social movements that emerged in the 19th century (labor, anarchism, socialism, communism, feminism, environmentalism, peace, human rights) along with more recent incarnations of these as well as movements that emerged in the world revolutions of 1968 and 1989 (queer rights, anti-corporate, fair trade, indigenous rights) and even more recent ones such as the slow food/food rights, global justice/alterglobalization, anti-globalization, health-HIV, and alternative media). These varied popular forces, social movements, global political parties, and progressive national regimes have come together to varying degrees, for centuries in some cases, contesting the powers-that-be in the world-system. The New Global Left is the latest incarnation of a global left that has been engaging in world politics since before the rise of the abolitionist movement in the eighteenth century.

The explicit focus of the global justice movement on the Global South is similar in many respects to some earlier incarnations of the Global Left, especially the Comintern, the Bandung Conference and the anti-colonial movements. The New Global Left contains remnants and reconfigured elements of earlier global lefts, but it is a qualitatively different constellation of forces because 1) there are new elements; 2) the old movements have been reshaped; and 3) a new technology (the Internet) has been used to try to resolve North/South issues within movements, and contradictions among movements.

Additionally, there has been a learning process in which the earlier successes and failures of the Global Left are taken into account in order to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past. Relations within the family of anti-systemic movements and among populist regimes are both cooperative and competitive. This needs to be brought out into the open so that cooperative efforts may be enhanced and global collective action for restructuring the world system may be more effective.

Sidney Tarrow (2005) asserts that coalitions1 are usually formed to combat a common threat or take advantage of an opportunity; hence the often-temporary nature of coalitions. According to Tarrow, four elements are necessary to sustain a coalition over time. Members must:

- Frame the issue that brings them together with a common interest.

- Trust in each other and believe that their peers have a credible commitment to the common issue(s) and/or goal(s).

- Have a mechanism(s) to manage differences in language, orientation, tactics, culture, ideology, etc. between and among the collective’s members (especially in transnational coalitions).

- Share incentives and benefits of participation.

Certain challenges confront transnational social movements to a greater degree than their localized counterparts. They encounter and must overcome tremendous gaps in basic communication, values, modes of political expression, and availability of resources. All these factors undermine the ability to construct mutual identification and trust. These differences exist within and between social movement industries. Nevertheless, transnational social movements have been working on these problems for centuries. The availability of less costly technologies of communications and transportation has proven a promising opportunity for international organizing.

The New Global Left contains remnants and reconfigured elements of earlier global lefts, but it is a qualitatively different constellation of forces...

Our research on the World Social Forum has produced maps of the network of movements that are involved in the social forum process. These maps represent the interlinked structure of the left wing portion of global civil society.2

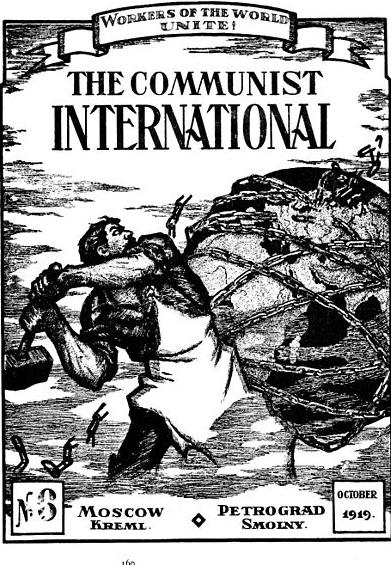

The history of broad-based left wing movement coalitions in earlier periods is arguably of relevance to understanding the processes of articulation among movements in the contemporary world revolution. The 3rd International (Comintern) was a coalition of red networks assembled to coordinate the political actions of communists in the years after World War I. It was in this context that a transnational group of communist intellectuals claimed to lead the global proletariat in a world revolution centered on addressing the fundamental issue of private property.

The Comintern adopted its own statutes at its second congress in 1920, was led by an executive committee and a presidium, established congresses with representatives from all over the world who were to meet “not less than once a year,” organized a number of other “front organizations,” and held multinational congresses attended by people speaking at least forty languages. The largest of these congresses had over 1600 delegates attending, underscoring the basic and critical communication problems every diverse group faces.3 The Comintern was abolished in 1943.

Paul Mason (2013) reminds us that threats from other social movements pose challenges that drive former sectarians to try to be more inclusive.

The United Front originated as an effort by communists to create an alliance with other socialists, peasants and all workers. The Popular Front was an even broader coalition that included all those who were willing to oppose fascism. David Blaazer’s 1992 study of Popular Front leaders in Britain shows that many of the non-communist participants were committed democrats and socialists, willing to work with communists in order to mobilize the fight against fascism. The forces of divergence in the global left of the 1930s were partly overcome by the dangerous rise of fascism.4 In the midst of this cooperation the Trotskyists proclaimed a Fourth International in 1938, and after fascism’s demise at the close of World War II, the left fragmented again in most countries.

Does this story have implications for the present and the near future? Is there a functional equivalent of fascism that could drive elements of the New Global Left closer together or alternatively serve as a driving force for the organization of capable new instruments of global political activity? Bill Robinson (2013) contends that the rise of “21st century fascism” in the guise of a globally coordinated police state could become such a large threat as to force divergent elements in the New Global Left to compromise some of their distinctive principles in order to put together more pragmatic instruments with which to counter 21st century fascism.

Editor's note: A longer version of this essay was presented as a paper at the Santa Barbara Global Studies Conference on March 1, 2014, hosted by the Orfalea Center for Global and International Studies, University of California, Santa Barbara.

1 See also Van Dyke 2003; Van Dyke and McCammon 2010

2 For more information on this research see the longer versions of this paper at:

3 Sworakowski, 1965:9

4 See also the essays in Graham and Preston, 1987

Bandy, Joe and Jackie Smith. 2005. Coalitions Across Borders: Transnational Protest and the Neoliberal Border. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Blaazer, David. 1992. The Popular Front and the Progressive Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chase-Dunn, C. and Matheu Kaneshiro. 2009. “Stability and Change in the contours of Alliances Among movements in the social forum process,” Pp. 119-133 in David Fasenfest (ed.) Engaging Social Justice. Leiden: Brill.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher, Christine Petit, Richard Niemeyer, Robert A. Hanneman and Ellen Reese. 2007. “The contours of solidarity and division among global movements.” International Journal of Peace Studies 12,2: 1-15 (Autumn/Winter).

Chase-Dunn, C. and R.E. Niemeyer. 2009. “The world revolution of 20xx,” Pp. 35-57 in Mathias Albert, Gesa Bluhm, Han Helmig, Andreas Leutzsch, Jochen Walter (eds.) Transnational Political Spaces. Campus Verlag: Frankfurt/New York.

Gill, Stephen. 2000. “Toward a post-modern prince?: the battle of Seattle as a moment in the new politics of globalization.” Millennium 29,1: 131-140.

Goldfrank, W.L. 1978. “Fascism and world economy,” Pp. 75-120 in Barbara Hockey Kaplan (ed.) Social Change in the Capitalist World Economy. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Graham, Helen and Paul Preston (eds.) 1987. The Popular Front in Europe. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Hochschild, Adam. 2005. Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire’s Slaves. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Juris, Jeffrey S. 2008. Networking Futures : the Movements Against Corporate Globalization. Durham, N.C. : Duke University Press.

Mason, Paul. 2013. Why Its Still Kicking Off Everywhere: The New Global Revolutions.

Martin, William G. et al. Making Waves: Worldwide Social Movements, 1750-2005. 2008 Boulder, CO: Paradigm

Moghadam, Valentine M. 2012. “Anti-systemic Movements Compared.” In Routledge International Handbook of World-Systems Analysis , edited by Salvatore J. Babones and Christopher Chase-Dunn. New York: Routledge.

Morrow, Felix. 1974 [1936]. Revolution and Counter-revolution in Spain. New York: Pathfinder Press.

Reitan, Ruth. 2007. Global Activism. London: Routledge.

Robinson, William I. 2013. “Policing the global crisis” Journal of World-Systems Research. Volume 19, Number 2:193-197.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. 2006. The Rise of the New Global Left London: Zed Press.

Smith, Jackie and Dawn Weist. 2012. Social Movement in the World-System. New York: Russell-Sage.

Smith, Jackie, Marina Karides, Marc Becker, Dorval Brunelle, Christopher Chase-

Dunn, Donatella della Porta, Rosalba Icaza Garza, Jeffrey S. Juris, Lorenzo Mosca,

Ellen Reese, Peter Jay Smith and Rolando Vazquez. 2014. Global Democracy and the World Social Forums. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers; Revised 2nd edition.

Steger, Manfred B., James Goodman & Erin K. Wilson. 2013. Justice Globalism: ideology, crises, policy. London: Sage.

Sworakowski, Witold S. 1965. The Communist International and Its Front Organizations. Stanford, Calif., Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace.

Tarrow, Sidney. 2005. The New Transnational Activism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Van Dyke, Nella. 2003. “Crossing movement boundaries: Factors that facilitate coalition protest by American college students, 1930-1990.” Social Problems 50(2):226–50. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/sp.2003.50.2.226

Van Dyke, Nella and Holly J McCammon (eds.) 2010. Strategic Alliances: Coalition Building and Social Movements. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 1990. “Antisystemic movements: history and dilemmas” in Transforming the Revolution edited by Samir Amin, Giovanni Arrighi, Andre Gunder Frank and Immanuel Wallerstein. New York: Monthly Review Press.

2004 World-Systems Analysis. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Zald, Mayer N. and John D. McCarthy. 1987. Social Movements in and Organizational Society. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books.