Queer Epistolary as Method in Migration Studies

archive

Debanuj DasGupta and Eyad Jabary with artists and activists at the Museo Nacional de la Inmigración at Buenos Aires

Queer Epistolary as Method in Migration Studies

Migration is an embodied process. Crossing borders in order to seek safety from persecution, torture, genocide, or escaping war leaves an imprint on the human psyche. This article highlights how queer migrants1 experience trauma of displacement and geopolitical conflicts at the scale of the body. The melancholia of dislocation is felt as an external excessive force leaving the queer migrant perpetually outside of home and communities of origin (DasGupta, 2014 & 2019; DasGupta & DasGupta, 2018; Gorman Murray, 2009; Reddy, 2005; Yue, 2000). The queer migrant is left hanging in-between nation states, ethnic and sexual communities, perpetually as an outsider, waiting full inclusion into the life of the nation-state (Aizura, 2018; Rodriguez, 2003 & 2014; Shaksari, 2020). This space of in-between nation-states is a real location, an assemblage of places that the queer migrant inhabits, while forging new emotional geographies as a form of queer migrant world-making (Rouhani, 2019).

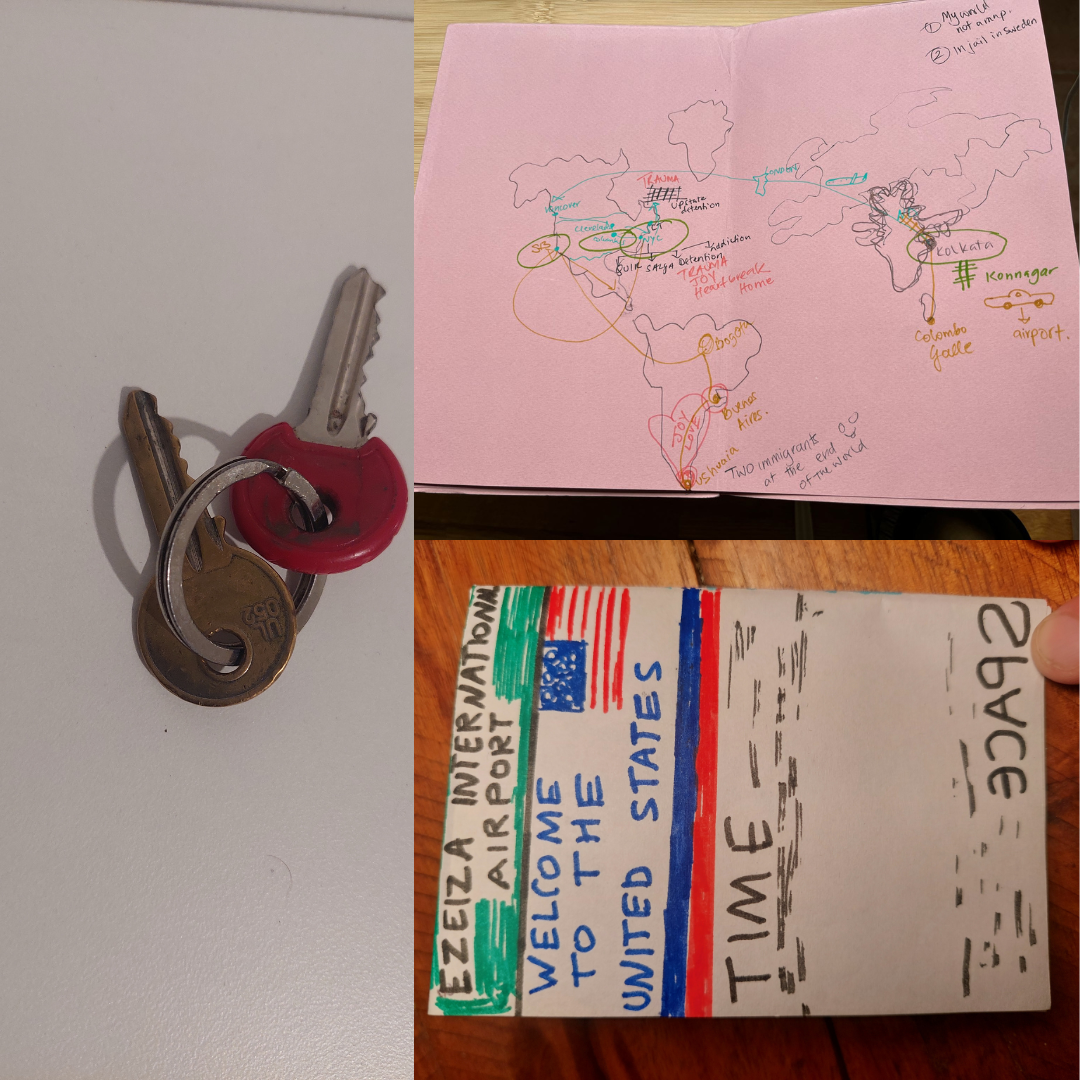

This article highlights exchanges between two friends and across two different subject positions; one of us is a researcher about queer migrations, and a one-time detainee as well as undocumented immigrant and one of us is a refugee escaping war in Syria and living in Buenos Aires. Both of us identify as gay and one of us identify as gender queer. We met during a research trip of mine in Buenos Aires, and remain in communication with each other while collaborating on a public humanities project. In our letters we offer love for each other through reflecting on each other’s experiences with war, displacement, surviving immigration regimes and chronic illness. As friends who care about each other, our letters (as well as in-person exchanges) are a form of being witness to each other’s struggles. Our letters attempt at forging emancipatory love (Sandoval, across the hemispheres (Sandoval, 2002). Our exchanges gesture toward the transference of trauma as we listen to painful experiences from our lives. Trauma experienced with escaping military persecution, living as undocumented person with HIV, and dealing with deportation proceedings. The letters offer us with an external framework through which we theorize how migration produces sexual risks as well as newer opportunities for the queer migrant subject. Along with the letters, we have exchanged handmade Zines and social media posts about our trips. We assemble sketches, words, and objects such as airline boarding passes, old keys and T-shirts. Such an assemblage art inverts scripts of the global security apparatus that frames queer migrants only as a victim in need of saving. Whereas, our affective assemblage reveals how in our attempt to communicate the trauma of displacement to each other, we are forging new emotional geographies.

Images of maps, Zines, and objects mentioned in the article

The article builds upon queer epistolary as a liberatory method, in order to carve a “theory in flesh,” (Moraga, 1983) about how queer migrants experience global apparatuses of migration, and how we are building a sense of belonging that is scattered across time and space. In conclusion we argue queer migration studies is predominantly engaged with questions about the law, asylum and refugee procedures and how activist communities are responding to such global regimes of migration. Whereas, the embodied and affective dimensions of queer/trans refugee & migrant life is yet to be fully taken up in queer migration studies. In a series of exchanges via letters, our travel together to the “Fin del Mundo,” (the end of the world) and handmade Zines, we offer ways to think about how migration regimes leave a mark on our bodies and emotions, and how queer epistolary as an exchange between friends offers liberatory frameworks, a site for building transformative justice with each other.

The Letters

Although you've given me the privilege of calling you Bobby as your parents did, today I choose to address you using your real name because this is what you represent to me; authenticity.

Yesterday you asked me what immigration meant to me. As I was too excited about our imminent visit to the "End of the World Prison", I probably gave you a generic answer that left a lot to be told.

I think about it today against the backdrop of Ushuaia's haunting aura. I think about the steps that trodded this land; indigenous people who made a life out of this rough land, the "settlers" who called this place home, the prisoners who were brought from far and wide and helped build the place, and tourists relishing king crab and cocktails before hopping on the next excursion, and I ask myself: isn't immigration everywhere?

I go back to the day I first met you at Palermo Hollywood with other queer immigrants. My first impression was: "another university professor who wants to do research on queer migration... Ok". I got the chance to know you more, and I heard your story through your TEDtalk. I couldn't imagine how the person standing in front of me had been through all of this, processed it, and made something beautiful out of it. Now I know that migration is not merely a "subject" for you. It encompasses everything that made you who you are today! My mind can't help but think about my own story and the escape from Syria. And I think again: if it wasn't for my own migration, I wouldn't have met you, and we wouldn't be here at the end of the world.

Yes, migration is everywhere and at the heart of everything. I dream of a day when human migration would be as easy as birds migration. Too poetic for a refugee representative at UNHCR, but a dream that will come true at some point in the future I'm sure.

Debanuj, I value your passion and effort, am so happy to be in contact with you, and looking forward to working with you on whatever would make this planer a bit better for migrants.

All the best,

Eyad Jaabary

Debanuj DasGupta

Jan 5, 2023, 11:47 AM

to Eyad

Dearest Eyad, our friendship is the pulsating beat of my heart reminding me that I am divine. We have spent so much time around each other, that I know the smell of your body… your being. Smell reminding me of bodies and pleasures. Friendship is an ethical use of pleasure-a Zone of intimacy where I am undone. Our friendship brings me to the porosity of the self, your laughter, ideas, care & love entering through my pores-reminding me that I am given unto others.

This story called Debanuj is afterall a repetitive narrative. I repeat the stories to make sense of myself. I repeat and repeat, replay incidents in my head, in order to tell you who I am.

I am

I

Eye

these eyes look, scan, record, remember

Eyes that see & narrate the world.

Your eyes

Your eyes have seen war, destruction @ horror

My eyes have seen empty apartments, abandoned neighborhoods, trap houses, and the insides of a detention cell.

I wrote from this place, heart open, stories about self & the other. For migration isn’t a singular story. As you say migration is everywhere.

Eyad

on identity and affect

I am not going to theorize on identity here. I am simply trying to express how my identity “feels” after five and a half years of being in Argentina. As no single word could do it, here is how I perceive my identity in different terms: liquid, in between, limbo, floating, shifting, omnipresent, everchanging, (and many more) . I am Eyad and Eddy, I am an English teacher que te habla en español و يشعر باللغة العربية (speaks Spanish and feels in Arabic). I am “The Argentinian” for the Syrians, and “El sirio” for Argentinians. I love this place with all my heart and feel real belonging to it. At the same time my soul was forged in Syria.

I am all of that, and beyond, because of migration.

Our bodies and memories are definitely “personal archives” that we hold on to tell our stories. Take the tone and timbre of our voices for example, our body languages, and the psychological processes involved in our analysis of things. These are subtle, dormant hues of who we are; they inhabit our DNA and remind us of what we have been through. In my eyes I see that thoughtful, slightly melancholic gaze of my mother. The way I speak reminds me of her rhythm and cadence. My dad gave me the shoulder shape, and his intensity of passion. That is how I hold on to my deceased parents, and how they still live on through me. My staccato accent that sometimes comes out when I speak Argentinian Spanish is something I embrace and hold dearly to my

heart.

These archives sometimes are objects that we keep, despite their functional uselessness, because they keep that thread of our past and present alive. I have the keys to my apartment in Latakia, and no, they are not old and rusty :) Two shiny silver keys in plastic protection: The red plastic is for the building gate, the blue plastic is for the apartment. They have been with me to the institute where I worked, waited in bus and grocery lines, attended funerals, been copied and given to friends who came to stay over. Well, the apartment is now sold, probably redecorated into a fancy place, and definitely keyholes were changed. The original keys flew to Buenos Aires with me. Now they are sleeping soundly in a little box, dreaming of old days when they signified Home

Sweet Home.

And what can I say about clothes? I have one old yellow T-shirt. So old it has holes in it. My friend calls it Sponge Pop because of its color and shape. I only recently stopped wearing it, mainly for public image and decency. Well that t-shirt has literally been through hell. For some strange reason, I always wore it to the military recruitment center, where it witnessed appeals for delay of service, shouts to stand outside the office until the god-like head of center calls you, and the worst disappointment when I was denied the opportunity to leave the country legally. It is now folded decently in my closet, next to a Shiny dark blue coat that my mom bought me when I was 18

(it is still as good as new)!

What more can I say, papers, boarding passes, pieces of music that I listen to, my military service document that was never eventually used, and it is here with me to remind me that the dictatorship is still there. I could go on and on forever, but I know I am exceeding the word limit.

Hope to hear from you soon, and to know about your views regarding the questions under discussion.

All the best dear Bobby,

Eddy

CODA:

In his letter Eyad mentions two shiny keys, an old yellow T-Shirt with holes, and boarding passes. These objects hold meaning for Eyad. In the Zine, we both sketch maps of the world based on our travels, along with locations where we might have significant connections but are unable to travel. The map and the objects we mention to each other gesture toward objects that remain, and yet the objects are affective ways of being in this planet. One in which the queer migrant is always holding onto to the lost past, while attempting to build new friendships. We remain witness to each other’s pain. I am able to travel to India, after having become a US citizen. Yet how does one account for the fifteen years of not being able to visit one’s family and homeland? How does one catch up to lost income and time? Eyad is presently a citizen of Argentina, working with international development agencies. Yet, as his letter states he is forever the “El Sirio,” for Argentines. Our shifting migration status might offer us travel, residency and work privileges but racially we remain outsiders, foreign and in exile.

The letters are now a part of a growing archive of letters shared between twelve friends who hold different kinds of immigration status, identify as LGBTQ+, and are currently residing in countries away from their home. Eddy has been living in Argentina since 2017. He was able to receive refugee status in Argentina through Programa Siria that allowed Argentine citizen to be sponsors and assist in the resettlement of refugees escaping war in Syria. Eddie was escaping serving in the Syrian military. He narrated to me that he felt unsafe as a queer person joining the military, and was also morally opposed to war. Eddy did not want to reveal his queer identity while in Syria, thus during his refugee resettlement process his sexuality was not part of the official story. Coming to Argentina offered Eddie with a queer friendly landscape in the middle class Buenos Aires neighborhoods where he got transplanted. Eddy’s journey across the globe from Syria to Argentina via Lebanon and France reveals a different route to queer migration than that of many queer migrants who move to the US or the UK. Eddie’s story challenges queer migration studies to take up south-south migratory routes rather than being solely focused upon south to north migrations. Future scholarship in queer migration studies ought to pay attention to the psychic life of queer migrants journeying through countries in the global south.

Our letters offer glimpses of the pulsating and enduring queer refugee body. We share the remains of trauma that hold potentials for forging friendships based on shared identification through the carnal and the tactile. Such identification cuts through the different hemispheres in which we are situated creating a rather queer geography of friends across borders. Perhaps, like the time Eyad and I were on a cruise boat at the end of the world, where the borders of Chile and Argentina kiss each other, the Atlantic and Pacific dances as the waves gently lap on the pebbles not as a crashing queer refugee counter public, rather an everyday endurance, being and becoming…

being,

just being,

being with each other.

*Funding for this project provided by the University of California Humanities Research Institute

- The word queer migrant and refugees is used as an umbrella term to signify persons who do not conform to sex/gender normativity in their country of origin thus facing torture, persecution, rape. The person is needing to escape their country seeking safety from persecution and torture. Thus Queer signifies diverse gender identities and sexualities who are seeking shelter in a different country, and remain displaced across borders while waiting to receive refugee or asylee status.

Aizura, A. 2018. Mobile Subjects: Transnational Imaginaries of Gender Reassignment. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

DasGupta, D. 2019. “The Politics of Transgender Asylum and Detention.” Human Geography, 12 (3), 1-16.

-----------------2014. “Cartographies of Friendship, Desire, and Home; Notes on Surviving Neoliberal Security Regimes.” Disability Studies Quarterly. Vol 34 (4).

Appears at https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v34i4.3994 Accessed on 06/22/2024

DasGupta, D & DasGupta, R. 2018. "Being out of place: Non-belonging and queer racialization in the UK." Emotion, space and society 27 (2018): 31-38.

Gorman-Murray, A. (2009). “Intimate mobilities: emotional embodiment and queer migration.”

Social & Cultural Geography, 10(4), 441–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360902853262

Moraga, C. 1983. “Entering the Lives of Others: A Theory in the Flesh.” In This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, edited by Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa, 23-24. New York: Kitchen Table, Women of Color Press.

Reddy, C. 2005. “Asian diasporas, neoliberalism, and family: Reviewing the case for homosexual asylum in the context of family rights.” Social Text 84: 101.

Rodriguez, J. 2003. Queer Latinidad: Identity Practices, Discursive Spaces. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

---------------2014. Sexual Futures, Queer Gestures and Other Latina Longings. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Rouhani, F. (2019). Belonging, desire, and queer Iranian diasporic politics. Emotion, Space and Society, 31, 126-132.

Shakhsari, S. (2020). Politics of rightful killing: Civil society, gender, and sexuality in Weblogistan. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Sandoval, S. 2002. “Dissident globalizations, emancipatory methods, social-erotics.” In Queer globalizations: Citizenship and the afterlife of colonialism. Edited by Arnaldo Cruz-Malave and Martin F. Manlansan. New York, NY: NYU Press.

Yue, A. (2000). “What's so queer about Happy Together? aka Queer (N) Asian: interface, community, belonging.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 1(2), 251-264.