Diplomacy of Masks: China and the Crisis of Populism in South America

archive

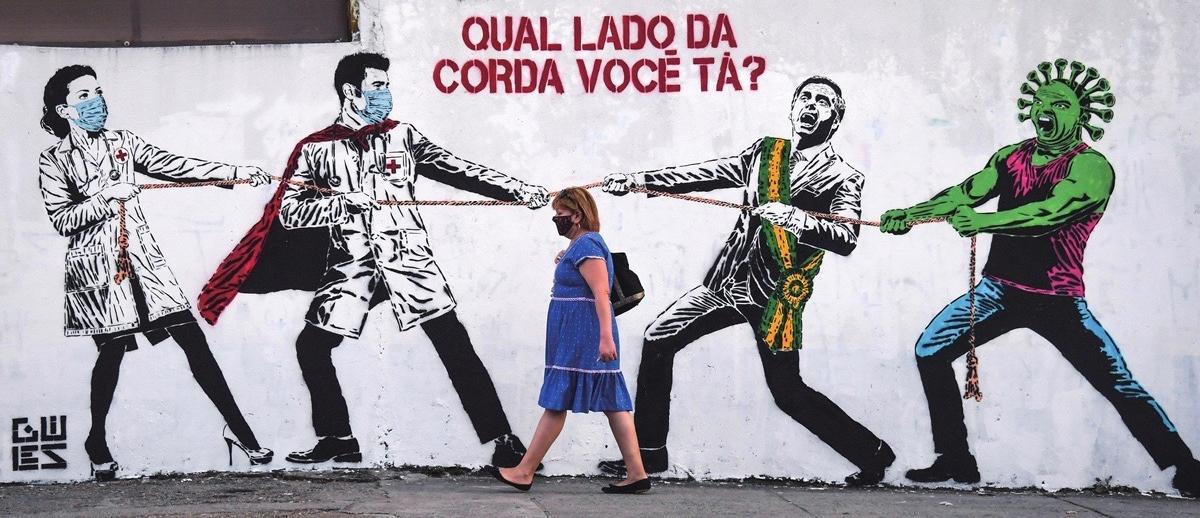

"Whose side are you on?" Street mural in São Paulo, Brazil.

Diplomacy of Masks: China and the Crisis of Populism in South America

In South America, the era of the “Beijing Consensus” seemed to end catastrophically in the month of February 2020. With the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil, Ecuador, and across the continent, China was held responsible and demonized. Chinese workers, students, and business leaders were attacked (in the media and sometimes in the streets). Those who could afford to flee did so and those who couldn’t vanished behind closed doors. Dozens of megaprojects financed and staffed by Chinese were abandoned and many more seemed doomed for extinction. Economies crashed in February, as did the prices of the natural gas, minerals, and agrobusiness commodities that Chinese traders had favored. COVID’s arrival in South America seemed to mark the definitive end to a booming era of cooperation with China.

But only a few weeks later, to everyone’s surprise, the tide reversed, as Chinese diplomats, businesspeople, and social media influencers initiated a new wave of humanitarian interventions, charm initiatives, and financial packages. China morphed from being the cause of a global pandemic and economic catastrophe to being these crises’ only reliable solution. In an unprecedented move, Chinese representatives, speaking Spanish and Portuguese fluently, presented themselves for news-media interviews across South America. They broke diplomatic protocol and aggressively spoke out against right-wing leaders and their policies. And they launched onto Twitter and Instagram and gave birth to Whatsapp groups in a flourish of social-media activity. The famously discreet profile of China in Latin America was suddenly substituted by one of open and charismatic visibility. China’s private sector and public sector leaders flooded South America (particularly Brazil, Ecuador and Bolivia) with medical supplies, doctors, and offers of new manufacturing, military, and agrobusiness partnerships and infrastructure finance. China launched a “Health Silk Road” with a massive donation of protective PPE gear and facemasks.

This initiative became known as the “Diplomacy of Masks,” a term tinged with more than a little irony. Was this new humanitarian agenda masking something? What interests and objectives were behind it?

In order to understand this epochal shift, it is important to remember that during the preceding fifteen years or so, China’s investors, military institutions, and diplomats had aligned with leaders of South America’s neo-developmentalist “Pink Tide”—that is, its statist, left-leaning governments, from Chavez’ Venezuela, to Lula’s Brazil, to Kirschner’s Argentina, to Morales’ Bolivia, to Correa’s Ecuador. Together, they launched an unprecedented series of megaprojects (dams, ports, railways, roads, arenas), agrobusiness plantations (soy and poultry), and extractivist ventures (natural gas, oil, copper, lithium, iron, and gold). As a result, China surpassed the US and Europe as South America’s number-one trading partner. But at what cost? The tragic down-sides of these arrangements have become apparent in terms of environmental damage, displacement of urban communities and indigenous nations, the extension of mechanized and militarized plantation agrobusiness, and the disintegration of the Amazonian, Cerrado, and Andean biomes.

During the 2000s and 2010s, leftist political leaders, such as Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in Brazil and Rafael Correa in Ecuador, championed these partnerships with China as promising examples of anti-imperialist or “south-south brotherhood,” “friendship,” and even “marriage.” Meanwhile, voices of recently hegemonic right-wing populist extremism in South America savaged the Beijing Consensus developmentalist model because it involved state coordination (of wholly capitalist investments), and because it involved Asian displacement of US and white hegemony, which the right saw as a racial and civilizational menace. New authoritarian populists in South America declared China’s close relationship to the Pink Tide to be a “communist plot,” a racial betrayal of “Westernness,” and as a series of giant corruption scams.1

Both the left’s Pink Tide and the extreme right’s populism represent China anachronistically, articulating the Beijing Consensus as a Third Worldist model. They both describe China’s interests in South America as a Maoist revolutionary agenda opposed to capitalism and imperialism—as if we were still in the 1960s-1970s age of the Non-Aligned Movement. They merely disagree over whether this anachronistic fantasy-model is wonderful or terrible. Both sides’ intentional, ideological misrepresentation of the economic, socio-cultural, and territorial presence of Chinese finance, extractive, and infrastructure projects means that there has been very little room in political or public spheres to assert non-fantasy, alternative models for truly empowering south-south solidarity. One could say that the problem is not that the neo-developmentalist model centers the Chinese, but instead that it seduces both left and right in ways that intensify class polarization, social militarization, and ecological devastation.

Chinese representatives, speaking Spanish and Portuguese fluently... broke diplomatic protocol and aggressively spoke out against right-wing leaders and their policies.

As youth environmentalists, indigenous and Black social movements, Chinese social media influencers, and peasant and labor activists across South America have been arguing, a much more interesting, sustainable, alternative model of south-south solidarity would be one that advocates anti-racist acknowledgement of the role of Chinese workers, farmers, and engineers in the past and future of South American society. This alternative would create space in South America for the mobilization of indigenous sovereignties, non-extractivist ecologies, local economies, small businesses, and non-patriarchal governance practices. Moreover, it would facilitate the dismantling of the catastrophically destructive mechanized agrobusiness monocultures, paramilitarized plantations, and oligarchical contractor operations to enable justice for workers and campesinos as well as opening the door to truly progressive forms of transregional cooperation. Will this kind of alternative model for ecologically sustainable, socially just south-south solidarity between South America and China emerge as a response to the faltering power of right-wing populism across the region? To address this question, a brief examination of the case of contemporary Brazil might be illuminating.

The Consortium of the Northeast

Whereas recent elections brought new right-wing leaders to power at the federal level in Brazil, and across the wealthier south and southeast of the country, in the northeast and much of the Amazon, left-leaning governors consolidated their popularity.2 These governors have come together to form the “Northeast Consortium” in order to implement quarantine policies, lobby for PPE and medical supplies, and to create an ethic of public service and public health that explicitly rejects the denialism of the Bolsonaro administration.3

Qu Yuhui, a Chinese diplomat in Brazil, speaking out against President Bolsonaro's anti-Chinese xenophobia. (Photo credit: Wilson Dias/Agência Brasil)

But the consortium also has an explicit geopolitical agenda. The Northeastern states have championed the “diplomacy of masks” and launched bold alliances with Chinese officials, business leaders, and medical researchers. This has enabled them to consolidate an alternative model for public health response. Due to the extreme poverty and inequality that persists in the region, its populations would be likely to suffer from the pandemic disproportionately. But there are many signs that the Consortium’s efforts, in partnership with China, have had some consistently positive effects. The downside to this effort is that it might be acting to re-legitimize Chinese megaprojects that would replace Amazonian forests with agrobusiness plantations and mining operations, while displacing poor and indigenous communities with pipelines and trucking roads to facilitate commodity and mineral exports.

“Pragmatism” and Militarization

Another set of institutional and political responses that have triggered a crisis of populism, and recentered China as a partner, is the mobilization of Armed Forces leaders and agrobusiness interests in Brazil behind what they call a “pragmatic” policy. This alignment is distinguished from the explicitly ideological and openly racist anti-China policy of Bolsonaro and the “Carvalho cult.” In this context, “pragmatism” is defined as taking advantage of the economic opportunities offered by Chinese investments in order to foster economic growth and increase export revenue. Does this doctrine of pragmatism signal a new consensus between right-wing military-agrobusiness interests, national capital, and a revived Pink Tide statist extractivism? Or does pragmatism simply roll the clock back to a comprador model of peripheralization for Brazil? Either way, this pragmatism doctrine ignores the warnings of the newly vibrant offshoot of “dependency theory”4 that remains wary of national capitalists as it tracks patterns of internal and transnational class formation and exploitation. This school of thought argues that transforming Brazil into a supplier of agricultural commodities and natural resources, mostly directed toward one massive purchasing country who is also the primary investor and engineer, creates a dynamic of dependent underdevelopment which is in fact reverse-development.

The Northeastern states have championed the “diplomacy of masks” and launched bold alliances with Chinese officials, business leaders, and medical researchers.

Among the proponents of this pragmatist policy are military leaders who have declared the entire Amazon region to be a security zone where they govern and mediate all economic and governance decisions. The Armed Forces have been arguing for decades that building a superhighway and supply rail through the middle of the country, bisecting precious Amazon ecosystems, is necessary for the security and prosperity of the nation. Also, among the pragmatists are investors in railways and ports that are to be carved out of indigenous territories, biodiverse ecosystems, and historic Black maroon communities. These trains, trucking roads, and ports are not to be built for the benefit of local peoples or workers but for the benefit of commercial elites. Instead they will detour around existing population centers and be used exclusively for shipping containers and grain vehicles for commodities directly to China.

A huge grain train is loaded in Palmeirante in the northern Brazilian state of Tocantins.

The Future

China therefore looms large in political calculations on both the left and right. Having been villainized during the early phase of the pandemic, it has restored its standing and become actively involved in humane and assertive responses to the COVID crisis. At the same time a new generation of articulate and charismatic young leaders has emerged who are standing up and speaking out against authoritarian populism. These voices include those of South Americans of Chinese origin and others with years of experience and commitment in the region. The massive impact of the “politics of masks,” the “Health Silk Road,” and the new pro-China “policy of pragmatism” has precipitated a crisis in authoritarian populism in Brazil and across the region.

But activists and social-justice leaders across the continent, and globally, are looking to reshape discourse in this moment, to mobilize a third path during this time of crisis to reveal alternatives to extractivism and dependency that do not expel China and its relevance. Instead, they center social and ecological justice and sustainability in these new initiatives to end the pandemic and foster equity through south-south cooperation.

_________________

Author’s note:

I would like to acknowledge with gratitude that this conversation and perspective has been shaped by my long-term research collaboration with Professor Fernand Brancoli at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, as well as by my brilliant researcher collaborators Professors Lisa Rofel of UC Santa Cruz, Professors Consuelo Fernandez and Maria Amelia Viteri-Burbano of the University of San Francisco de Quito. Many of these ideas will be developed in much greater depth in the context of an edited volume we are publishing together in 2021. Also, I thank my Global Studies colleague Professor Gustavo Oliveira at UC Irvine for his essential advice.

1. President Jair Bolsonaro is heavily influenced by the ardently racist, Sinophobic guru of new fascism, Olavo de Carvalho. And the leaders of the parliamentary coup in Bolivia in 2019 explicitly identified themselves as against the nationalization policies of Evo Morales who had seized Canadian and Swiss mining interests while making favorable deals with Chinese lithium developers.

2. This consortium groups together leaders of rival political parties of the left, including governors of the states of Bahia (Rui Costa), Ceará (Camilo Santana), and Piauí (Wellington Dias), and Rio Grande do Norte (Fátima Bezzera) who are all members of the Workers’ Party (the party of former presidents Lula and Dilma); the governor of the state of Amapá (Waldez Góes and the vocal Senator Cid Gomes of Ceará identified with the PDT (the Democratic Worker’s Party that led struggles against the military dictatorship in the 1980s); and the governor of Maranhão (Flávio Dino) identified with the Communist Party of Brazil (PCdoB).

3. In some ways this consortium of states held by political opposition leaders resembles the US pattern. There, Democratic governors of California, Washington, Oregon and Colorado have formed the Western Consortium to join forces for COVID policymaking and to make deals with China for supplies; or we could compare this to the case of India, where left-governed states of Kerala and West Bengal have advocated affective public health responses that are more effective and less repressive than those advocated by the federal government in Delhi.

4. This theory originated among economists in South America’s southern cone. The groundbreaking offshoot of this school that is focusing on working-class and peasant mobilizing includes the work of Felipe Antunes de Oliveira, currently a fellow at the Centre for Global Political Economy at the University of Sussex.

Macarena Gómez-Barris, The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives (Duke University Press, 2017)

Macarena Gómez-Barris, Beyond the Pink Tide: Art and Political Undercurrents in the Americas (University of California Press, 2018)

Jan Nederveen Pieterse, et al, eds. China's Contingencies and Globalization (Routledge 2018)

Gustavo Oliveira, “Boosters, Brokers, Bureaucrats, and Businessmen: Assembling Chinese Capital with Brazilian Agrobusiness,” Territory, Politics, Governance 7/1 (2019)

Javiera Barandiaran, Science and Environment in Chile: The Politics of Expert Advice in a Neoliberal Democracy (MIT Press, 2018)

Thea Riofrancos, Resource Radicals: From Petro-Nationalism to Post-Extractivism in Ecuador (Duke University Press, 2020)

David Dollar, China’s Investment in Latin America (Brookings Institution, 2017)

Margaret Myers and Carol Wise, The Political Economy of China-Latin American Relations In the New Millennium: Brave New World (Routledge, 2017)

Julia Strauss and Ariel C. Armony, ed. From the Great Wall to the New World: China and Latin America in the Twenty-first Century (Cambridge, 2013)

Gastón Fornez and Alvaro Mendez The China-Latin America axis: Emerging markets and their role in an increasingly globalised world (Springer, 2018)

Robert Evan Ellis China-Latin America military engagement: Good will, good business, and strategic position(Strategic Studies Institute, 2011)

Kevin Gallagher The China triangle: Latin America's China boom and the fate of the Washington consensus (Oxford University Press, 2016)

Alex Fernández Jilberto and Barbara Hogenboom, eds. Latin America facing China: South-south relations beyond the Washington consensus (Berghahn Books, 2010)

Evan Ellis China on the Ground in Latin America: Challenges for the Chinese and Impacts on the Region (Springer, 2014)

Rebecca Ray, et al China and Sustainable Development in Latin America, The Social and Environmental Dimension(Anthem Press, 2017)

Karolien van Teijlingen, Esben Leifsen, Consuelo Fernández-Salvador and Luis Sánchez- Vázquez (eds) La Amazonía Minada. Minería a Gran Escala y Conflictos en el Sur del Ecuador. (USFQ-Abya Yala, 2017).