Black City: The ‘Urban’ as Refusal and Abolition

archive

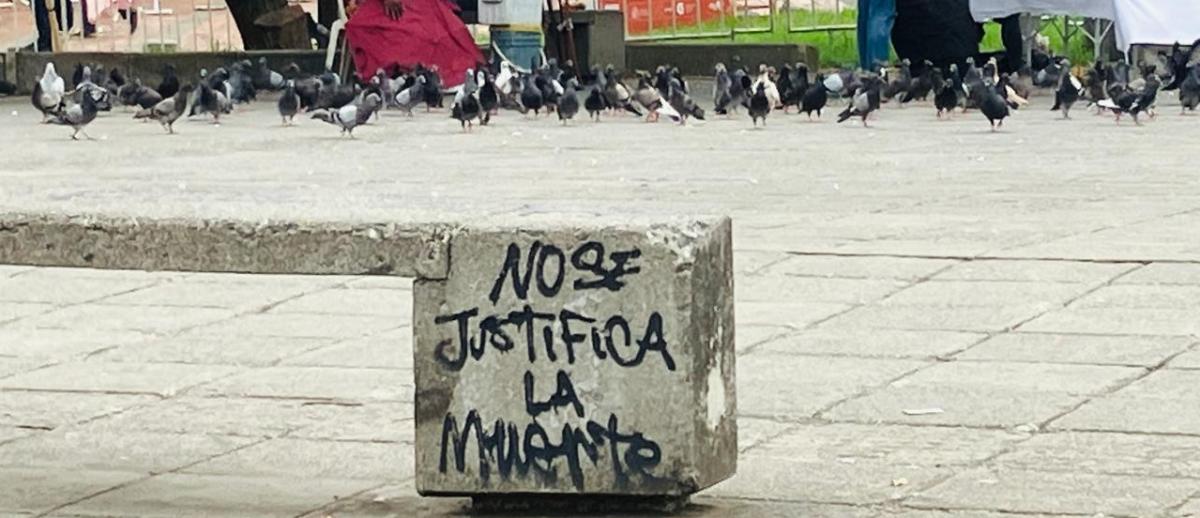

"Death is not justified" | Photo by Jaime Alves

Black City: The ‘Urban’ as Refusal and Abolition

Space of captivity? School fence in Aguablanca, a predominantly black district on the outskirts of Cali, Colombia | Photo by Jaime Alves

This special issue unsettles the urban as both a site of injury and refusal. As a privileged locus for organizing inequalities, the city reinforces the citizens/enemies and human/nonhuman divide, reinstating the time/space of the colony. At the same time, attentive to the rebellious impetus of Black urbanity, we are interested in clandestine forms of placemaking that refuse the city as a territory of confinement, dispossession, and death. These refusals may take the form of organized protests against police violence, urban riots against deportation, collective care by aggrieved communities, or even apparently dispersed self-serving practices such as bus fare evasion or a range of illicit economies from drug dealing, selling “loosie” cigarettes, or pirate copies of consumer goods. Much more diverse in scope and creativity, what these practices evince is a proposition on the urban not as an adjective but rather as a field of political struggle. As urban studies scholar Abdul Maliq Simone (2022) contends, the urban is how abolition is lived through an undetermined, not always coherent, set of practices that unsettles the city as ordered spatiality. “These spaces of simultaneous fugitivity, displacement, targeted extraction, and recomposition” make abolition an ordinary practice of inhabiting the city and Blackness as “the urban force” that unleashes both repression and invitation (Simone 2022, 32). The contributors in this series engage with this dual perspective, addressing the questions: what is this “invitation” that urban Blackness represents, and what would that mean to attend to its call? Moving across racialized cityscapes of Brazil, Colombia, and the United States, they help us to understand how the urban reproduces colonial injuries not only through policing, displacement, and extraction, but also through exclusionary definitions of citizenship and humanity that water down the revolutionary potentials of right-to-the-city politics.

Whose City?

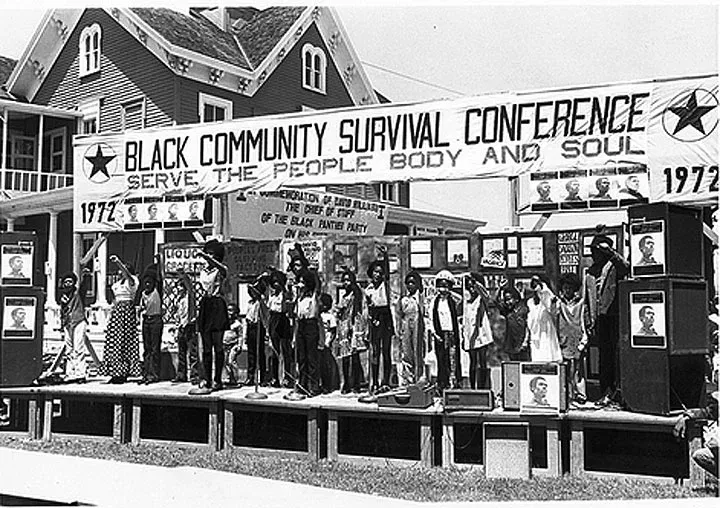

The Black Panther Party’s “Black Community Survival Conference.” BPP headquarter, Oakland, California 1972.

Although his radical proposition on the right to the city has been shaded by some “material” (and urgent) demands for urban citizenship such as housing, transportation, and employment, Henry Lefebvre (1996; 2003) saw the right to urban life as “a pratico-material realization” of a much more profound revolutionary program to reinstate the use-value of a city “no longer lived” and increasingly consumed as an object. He asked, “Would not specific urban needs be those of qualified places, places of simultaneity and encounters, places where exchange would not go through exchange value, commerce, and profit? Would there not also be the need for a time for these encounters, these exchanges (Lefebvre 1996, 109)?” This underappreciated call for a return to the use value of the city (in opposition to the exchange value imposed by urban capitalists and upheld by the ideology of urbanism) bears an insurgent potential that we desperately need to return to. One does not need too much abstraction to consider how urban life has been continuously assaulted, whether by international corporate landlords who have transformed renting into a permanent condition of extraction and eviction into a permanent mean of coercion (Fields et al., 2021), local governments that rely on law enforcement as a mechanism of urban-land valorization and real estate revenue in cities undergoing financial austerity (Beck and Goldstein, 2018)1, or self-deputized officers who enforce gentrification through “hostile privatism and defensive localism” to protect white spaces (Lipsitz 2011, 28). Even if we attend to these systemic conditions, “turn[ing] the right to the city into sectorial rights may be useful to translate concrete movement demands into tangible reforms, but if such tactical moves come at the expense of a broad, transformational perspective, they may become cases of misplaced concreteness” (Kipfer et al., 2013, 128-29). Even more, if not followed by critical appreciation of other spatial arrangements through which the poor pursue the right to the city much beyond state-backed citizenship rights (Simone 2005), these demands may underscore mystified representations of urban reality, subsuming to the ideology of urbanism.

Instead, we would do well in returning to Lefebvre for a much-needed revolutionary call to decolonize the urban, particularly in these troubling times when cities embody the multi-scale imperial spaces of war capitalism, debates surrounding the validity of his urbanization-supplanting-industrialization thesis notwithstanding (see Smith 2003). From São Paulo to Los Angeles, from Cali to Minneapolis, from Gaza to sanitized Santa Barbara (to implicate our own campus in this economy of violence), banishment, captivity, and extraction synergistically produce the city as a death-driven and value-producing dispossessed urbanity. What kind of violence is needed to produce Santa Barbara (the so-called American Riviera), for instance, as an ordered, sanitized, peaceful city? As my students of Black Cities would teach me, whitopia Santa Barbara (“Santa Bruta” is a more appropriate toponym by the native population) embodies the heterotopic space/time of ‘primitive’ and perpetual accumulation of capital from domestic assaults on Black and indigenous people and from the relentless accumulation of wealth from financial and military capitalism. It is the sanitized urban prototype of, to borrow a line from Shadia Drur (2024), manifest destiny gone global. The huts by the railroad that cut through the city, or the improvised homes of houseless individuals sleeping in the doorsteps of classic and warming Spanish-revival buildings home to global security companies and global financial institutions, remind us that the imperial city is not an abstract geography. Here, as in other urbanities, the dispossessed have been stripped even of the ‘right to shit,’ so to speak, as without affording to pay for an overpriced cappuccino (plus the enforced tips disguised as civility), they are denied a passcode to use a toilet. Santa Bruta indeed.

The Anticity

Banners flutter in the wind in anticipation of the end-of-year festivities in a marginal neighborhood of Cali. In the foreground, a “yielding” traffic sign with a bullet hole. Will life triumph? | Photo by Jaime Alves

How can we organize for the right to the city as Black when antiblackness is a powerful political resource for city-making to the point that Black inclusion is only conceivable through subordination and obliteration? If the city is the ‘new’ battlefield for enforcing the order of empire (Danewid 2020), how does vulnerability across race, class, gender, and location facilitate (and complicate) a global urban strategy against geopower? How do we bring the dispossessed, abject, disordered, and uncivil (those regarded as anticity) together for the much-awaited destruction of the city capital built? As the case studies in this series demonstrate, Black activists do engage with the lexicon and strategies of right-to-the-city politics to make concrete demands. Whether in post-independence Colombia, when former enslaved populations waged a “race war” to reclaim a share of the patria/ciudad criolla; in post-abolition Brazil, where defiant former slaves formed a maroon city within the white city; or during the troubling 1960s USA, when Black-led urban riots swept the country from Newark to Oakland, denouncing the Black ghetto as an “internal colony” and the police as an occupation force (Llano 2003; Tyner 2006; Alves and Vargas 2023), Black activists have pushed forward “practical” aspirations while also opening “ideational” space for radical political imagination (Bloom and Martin 2016, 13). Borrowing from these traditions, contemporary Black struggles challenge the very premises of the city as an accomplished, realized geography in which all the excluded long for is to be incorporated. These mystifications of the city as consolidated total space, which are perhaps what Lefebvre meant by the “blind field” of urban reality (Lefebvre 2003, 40-41), are challenged by the Black disputes of what the urban can and may be. For instance, wouldn’t the struggle to return the use-value of the city require us to reckon with the fact that the historical city was never available for those whose labor figures at best as antivalue?2 And yet, as the anti-force of urbanization, uncommitment to the mythical city Lefebvre lamented has disappeared, Black urbanity may indeed interrupt city-making as accumulation and thus defer the city as debt and death. If we are to use the lexicon of right-to-the-city politics to analyze Black urban struggle, then I would say it seeks not inclusion but rather to “enegrecer” (blackening) the right to urban life or, in Saidiya Hartman’s (2019, 34) proposition, to undo the city as an extension of the plantation. Black dwellers embrace the urban as refusal and refusal as abolition.

At the end of the day, everything boils down to a question my interlocutors from the Colombian city posed to me again and again when I tried to read their demands through the lenses of urban inclusion: “rechazamos esta ciudad blanqueada (we refuse this whitened city),” which I hear as “let’s radicalize the Lefebvrian call for embracing the urban as a field of possibilities!” They demand inclusion but not in the time/space coordinates of the plantation city where their bodies are devoured in the kitchen of the white/mestizo elites and in the sugar-fields surrounding it—where the mutilated bodies of their kids are now and then found as they fall prey to vigilant groups. Because their relation to the heterotopian multicultural city3 is one in which they inhabit the time of slavery, their real fight is to reclaim control over their lives, even if at times such demands for autonomy rely on the grammar of inclusion. In that sense, a true urban revolution would require decolonizing the ordinary towards the right of doing nothing, the right of “hacer lo que se nos dé la gana (do with our time what we please)” as they have it. This demand is so close to the skin, so straightforward, and so comprehensive that it may render the call for returning the use value of cities way too abstract. Give us our time back! We refuse to be owned! It is this rebellious impetus that the Blackcity, as a theoretical proposition, wants to invite and incite. Would the multiracial precariat of our time attend to the call of the familiar wretched of the global city to embrace the urban as abolition? Risking stretching an interpretation of Lefebvrian revolutionary thought, let’s say that blackness is the anti-city that will conquer the city!

1. Authors have established a correlation between the size of police departments, the size of black and Latino populations and house price indexes in US cities (Beck and Goldstein 2018). Others have shown how citations and fines have been deployed by city officials and law enforcement agents as a strategy of revenue maximization (Lipsitz 2011; Sobol 2015).

2. In Unpayable Debt, Denise Ferreira da Silva (2022, 273-74) makes the forceful argument that the Marxist theory of value negativized Black labor by regarding the colony as the “primitive” space where, contrary to the British factory, the contradictions of capitalism have not matured enough to entice a struggle for freedom and self-determination. This negativation (-) renders the wealth produced by the essential labor of black people unquantifiable and the black labor as antivalue.

3. Although other authors have used this concept, my uses of heterotopia are primarily inspired by Lefebvre in his reference to the “heterotopia of nature” and the homogenization of urban space. At the same time, he envisioned the urban not as an adjective or a static condition but rather as a heterotopic field of temporalities and spatial relations (Lefebvre 2003).

Alves, Jaime Amparo, and João da Costa Vargas. 2023. "Polis Amefricana: para uma desconstrução da ‘América Latina’ e suas geografias sociais antinegras." Latitude 17(3): 57-82.

Beck, Brenden, and Adam Goldstein. 2018. "Governing through police? Housing market reliance, welfare retrenchment, and police budgeting in an era of declining crime." Social Forces 96(2): 1183-1210.

Danewid, Ida. 2020. The fire this time: Grenfell, racial capitalism, and the urbanization of empire. European Journal of International Relations, 26(1), 289-313.

Drury, Shadia B. 2024. "Manifest Destiny Goes Global." Chauvinism of the West: The Case of American Exceptionalism. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

Fields, Desiree, and Elora Lee Raymond. 2021. "Racialized geographies of housing financialization." Progress in Human Geography 45(1): 1625-1645.

Giroux, Henry. 2014. "Militarism's Killing Fields: From Gaza to Ferguson. "Open Review of Educational Research 1(4): 8-19.

Hartman, Saidiya. 2019. "Wayward lives, beautiful experiments: Intimate histories of social upheaval." New Heaven: Norton Town.

Kipfer, Stefan, Parastou Saberi, and Thorben Wieditz. 2013. "Henri Lefebvre: Debates and Controversies." Progress in Human Geography 37(3), pp. 128-29.

Lefebvre, Henry.1996. The Right to the City. In: Writings on Cities by Henri Lefebvre, E. Kofman, and E. Lebas (Eds.) 63–182 Oxford: Blackwell. Available at: https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/henri-lefebvre-right-to-the-city

Lefebvre, Henry. 2003. The urban revolution (R. Bononno, Trans.) Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

Llano, Alonso Valencia. 2003. "¡Mueran los blancos y los ricos!: participación de los negros en el proceso de independencia del suroccidente colombiano." Colección Bicentenario 17 (3): 91-95.

Lipsitz, George. 2011. “The White Spatial Imaginary.” How racism takes place. Temple University Press, pp. 25-50.

Lipsitz, George. 201.1 Policing Place and taxing time in Skid Row. Policing the Planet, pp. 123-139.

Sobol, Neil L. 2015. "Lessons Learned from Ferguson: Ending Abusive Collection of Criminal Justice Debt." U. Md. LJ Race, Religion, Gender & Class 15 (2): 293-300.

Simone, Abdou Maliq. 2005. The right to the city. Interventions, 7(3): 10-17.

Simone, AbdouMaliq. 2022. The surrounds: Urban life within and beyond capture. Duham: Duke University Press.

Silva, Denise Ferreira Da. 2022. Unpayable Debt. Sternberg Press: London.

Smith, Neil. 2003. Foreword d. In H. Lefebvre, The urban revolution (pp. vii–xxiii). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Tyner, James A. 2006."“Defend the ghetto”: Space and the urban politics of the Black Panther Party." American Geographers 96(6): 105-118.