Varieties of Martyrdom

archive

Varieties of Martyrdom

Few days go by without seeing a martyr in the news. The so-called Islamic State presently dominates such stories from the Middle East, but Turkey’s propagandistic use of martyrs was recently featured in the New York Times. Martydom has also been a tool of political struggle in Tibet, where more than 140 protestors have self-immolated since 2009. Interestingly, the Chinese government, which is the target of these protests, has denied their significance while on the other hand expressing concern about the legacy of Communist Party martyrs. Yet the concept of martyrdom remains largely misunderstood despite its relevance in many different contexts around the world.

The term “martyr” comes from martus, a Greek word meaning a witness in a court. As it is used in Western culture, the concept’s character comes largely from the context of early Christianity, where it referenced those who died as a result of Roman persecution. These men and women were said to have been put on trial for professing themselves to be Christian, a religious identity seen as illicit and dangerous by the populace of the Roman Empire.

During the period when early Christians were martyred, the foundations of the Empire were understood to rest on the pax deorum, the arrangement between the people and their gods assuring prosperity for the former so long as the latter were revered. Christians were seen as belonging to a secretive group who did not recognize the traditional gods of Rome, and who preached about an imminent divine kingdom that would supplant the Empire.1

When Polycarp, one of the most well-known Christian martyrs, was arrested and brought to trial, he refused to perform the traditional sacrifices expected of all imperial subjects. Incensed, the Roman proconsul ordered the impertinent man be burned alive.2 Martyrs were commonly burned, stabbed, and set upon by hungry beasts that were unleashed by Roman officials aiming to coerce them to abandon their faith and pay homage to Roman gods. Many remained completely silent during their afflictions, while others joked or reprimanded the crowd.

The Martyrdom of St. Polycarp of Smyrna

Refusing to speak in any way that would betray their status as Christian, martyrs showed their commitment and loyalty to divine authority. When the authorities were faced with Polycarp’s simple defiance, the proconsul could only make him hurt in hopes of compelling him to admit he was obliged to follow Roman laws. Each failure by Roman officials was celebrated as a victory for the truth of Christendom.

Today, it is the Islamic context that dominates the discourse on martyrdom. Approximately seventeen centuries after Polycarp, the first “martyrdom operation”—more commonly known as “suicide bombing”—was performed in Lebanon in 1982.

The distinction is an important one, since suicide is forbidden in Islam while martyrdom is the height of religious action. Human beings strapping on explosives to covertly infiltrate a populated area before detonating have been interpreted as both.

The tactic would become widely associated with the Palestinian group Hamas (as well as the Sri Lankan separatist group the Tamil Tigers) in the 1980s and 1990s before being taken up by transnational groups like al-Qaeda and the so-called Islamic State. But it is generally seen to have originated with an attack perpetrated by fifteen-year-old Ahmad Qasir. Angered at Israel’s invasion and occupation of Lebanon, Qasir drove a truck with explosives into the Israeli barracks in Beirut initiating an explosion that killed over 100 soldiers and Qasir himself. He is remembered as a martyr by Hezbollah, a group regarded as a terrorist organization by some and as a legitimate political force by others. Over the past thirty years, it has been one of the three leading factions in Lebanon’s Parliament.

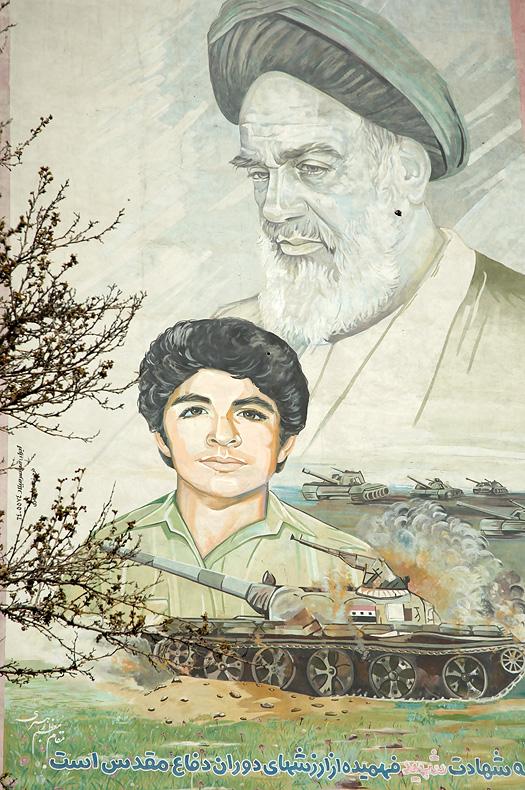

Mural depicting child martyr Mohammed Hossein Fahmideh and Ayatollah Khomeini

Lesser known is the story of thirteen year-old Mohammed Hossein Fahmideh, an Iranian youth who in 1980 blew himself up in an attack during the first Iran-Iraq war. Fahmideh was a member of the Iranian military’s Basij corps, known for their “human wave attacks” where rows of men marched to certain death in hopes of overwhelming and demoralizing the enemy. His act is still remembered in Iran today.

In Islam, the figure of the martyr represents those who lose their lives in service to God. Historically the term was applied to a variety of nonviolent forms of death by, for example, plague victims and women who died during childbirth, but the label has been increasingly reserved for those who intentionally give their lives in battle.3

The reinvigorated focus on militant martyrdom came in the twentieth century largely as a response to a widespread perception that corrupt secular governments ruled Muslim homelands, preventing people from living according to Islam.

The creation of the state of Israel in 1948 exacerbated the situation by displacing Palestinian Muslims and creating a widely shared experience of oppression.

Ideologues like Sayyid Qutb in Egypt and Maulana Ala Maududi in Pakistan fueled this trend by imagining an existence in which Islam intersected with political life so that nascent national identities encouraged by the post-WWII international system were outmatched or incorporated by religious identity, as evidenced by Ayatollah Khomeini in the Iranian revolution and by the very name Hezbollah, which means “party of God.”4 In precisely the same way that Christians sought the Kingdom of God, these groups dreamt of a society that could unite all Muslims into one nation under divine law. Creating such a world was encouraged under the banner of jihad—struggle in the path of God. What tradition calls the “greater jihad,” which referred to one’s struggle with personal desires, was eclipsed by the “lesser jihad” of militant struggle, as Qutb, Maududi, and their followers increasingly focused on martyrs who fall in battle.5

Although the Christian tradition represents martyrdom as an unfortunate but noble and passively accepted death, the Islamic version of the concept was formed by a different set of experiences, resulting in its more active character.6 The discomfort and anger that arises when the label of martyrdom is applied to someone whose violent death killed others reminds us that martyrdom is always an interpretive category, applied by those who agree with the martyr’s goals and ideals. But can the category of martyrdom encompass both violent and nonviolent deaths?

Although the Christian tradition represents martyrdom as an unfortunate but noble and passively accepted death, the Islamic version of the concept was formed by a different set of experiences, resulting in its more active character.

In a court, certain individuals are called upon to offer testimony to help determine the truth of a case. Their right to testify springs from expertise or experience, and the weight of their testimony depends on factors like their credentials and interest in testifying. If they benefit from giving certain information, they are considered less trustworthy, and the converse is also true; if their testimony does not provide personal benefits, their words are awarded a higher truth value.

This dynamic finds its apex in martyrdom. Just as the courtroom witness offers an interpretation of events or information, martyrs use their deaths to speak to their convictions about identity, authority, law, and cosmic order. I term these sovereign imaginaries: imagined frameworks that give shape to existence and imbue political authority with religious vigor. Religion and politics are inseparable in martyrdom; Polycarp was guided by a God whose laws superseded temporal authorities, and the groups who claimed Qasir and Fahmideh likewise constructed political activity as a sacred duty.

Martyrs are celebrated not because of their peacefulness or piety, but because each death conveys a truth about the world that is narrated in an exceedingly powerful way. Their willingness to be guided by a sovereign imaginary that demands death over disobedience is a powerful affirmation to group members of the importance of their guiding principles.

Whether violent or peaceful, that show of devotion enables martyrs to provide influential evidence for a certain way of understanding the world. While we will naturally embrace some applications of the label “martyr” and be repelled by others, the structure of martyrdom exerts extraordinary power due to its spectacular demonstration of a commitment that extends into the grave, where every martyr’s road leads.

Image source: Martyrs of Iran, Wikimedia.

1. Good discussions of this dynamic are available in Candida Moss, Ancient Christian

University Press, 2012) and Daniel Boyarin Dying for God: Martyrdom and the

Making of Christianity and Judaism (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999).

2. While early Christian martyr acts were invoked as rhetorical devices rather than

by the requirement to sacrifice to the Emperor and to “curse Christ” can be seen in

Pliny the Younger’s letters to the Emperor Trajan, which described this as the

appropriate method of trial. See his Letters X.95 and X.96.

3. David Cook’s clear analysis in his Martyrdom in Islam (New York: Cambridge

development of the shahid doctrine in Islam. For more in depth reading regarding

martyrdom in Islam today (including its history), see Meir Hatina Martyrdom in

Modern Islam (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

4. Roxanne Euben and Muhammad Qasim Zaman have gathered a collection of

analytical essays in their Princeton Readings In Islamist Thought: Texts and

Contexts from Al-Banna to Bin Laden (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press, 2009).

5. For one of the most comprehensive discussions on the issue see Michael Bonner,

University Press, 2006). David Cook too offers a coherent and accessible reading

of the jihad tradition in his Understanding Jihad (Berkeley: University of California

Press, 2005).

6. Husayn, the most revered martyr of Islam, is remembered for his brave stand

death was certain. Asma Afsaruddin gives a great deal of detail around the event

and its later interpretation in her Striving for God: Jihad and Martyrdom in Islamic

Thought (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).