Populism and Persecution in Myanmar, the United States, and Beyond

archive

Rohingya parent and child at Kutupalong-Balukhali camp in the Cox's Bazar district of Bangladesh.

Populism and Persecution in Myanmar, the United States, and Beyond

The past few years have seen populist parties and figures rise to prominence and influence in established democracies across the globe. With this trend there has been a corresponding increase in long-standing political and dehumanizing terminology together with problematic religious justifications for the violent treatment of individuals and communities of dissimilar or contested identities. The discourses of hyper-nationalism, xenophobia, and persistent prejudice have been exacerbated by the mainstreaming, and apparent public acceptance, of this aggression. In light of the recent resurgence of violence and displacement impacting the Rohingya, this essay compares a threefold system of othering used to justify persecution in Myanmar with similar rhetorical strategies utilized recently across the US. Even though the situation in the US isn’t as violent, one wonders what the future holds given the discursive similarities between the two contexts.

The Rohingya, long denied bureaucratic and legislative recognition in Burmese history, continue to face oppression based on their supposedly alien status. Like the 1982 Citizenship Law which omitted the Rohingya as a recognized national race, the 2014 census prohibited the use of the term Rohingya itself, leaving over one million people in the Arakan state unrecognized, with no legal or official political identity. In 2014, Yanghee Lee, the UN Special Rapporteur to Myanmar, was told that the government did not recognize the term. In 2016, the Information Ministry stated that “Rohingya or Bengali shall not be used. Instead ‘people who believe in Islam in Rakhine State’ shall be used.”

The Rhetoric of New Arrival

This denationalization is based on a deliberate denial of the long-standing existence of the Rohingya population within the country’s borders, and is supported by the many public and governmental references to the Bengali populations living within Myanmar. The rhetoric of newness, of being a foreign population that is unjustly and only recently occupying a portion of the country, is frequently used to justify political processes of forced migration and discrimination. It is premised on the ideology that the expulsion of the Rohingya people is not an example of injustice or persecution, but rather of appropriate border control. Explicit or not, the notion of ethnic and racial purity remains dominant in these discourses, as is the essentializing of a pure Burmese nation state, one that is defined in direct opposition to the existence of supposedly foreign communities and community members.

A similar condemnation of non-nationally recognized minorities can be heard in the language of populist movements across the US. Whilst Donald Trump’s infamous statements condemning all Mexicans as rapists and cartel members drew international ire, frequent references made by Trump and other populist figures concerning undocumented residents of the United States seem to elicit lesser degrees of outrage. On May 16th, 2018, Trump said, “We have people coming into the country, or trying to come in—and we’re stopping a lot of them—but we’re taking people out of the country…And because of the weak laws, they come in fast, we get them, we release them, we get them again, we bring them out.”1 Despite repeated incidences of individuals being deported from the US due to insufficient documentation, despite being long-term residents and business and home owners, populist rhetoric paints sweeping pictures of all undocumented individuals and communities as recently arrived, and as flooding the country.

The rhetoric of newness, of being a foreign population that is unjustly and only recently occupying a portion of the country, is frequently used to justify political processes of forced migration and discrimination.

The famous “Build A Wall” chant which echoed across Trump’s campaign trail was based on this deliberately perpetuated misunderstanding. Irrespective of the number of recently arrived individuals in the US (and elsewhere), the dominant populist rhetoric surrounding individuals and communities without citizenship is one of immediacy and unwillingness to acknowledge the large numbers of long-term, albeit unrecognized, residents. This portrayal deliberately obscures the complicated and often decades-long narratives of undocumented residents’ presence in the US, and cleverly deflects from conversations regarding the path to citizenship.

Religious Justification

Religious discrimination against the Rohingya within Myanmar frequently appears as a hybrid of hyper-nationalism and religious fundamentalism. Public representatives from the Burmese Buddhist national organization (the 969 Movement), and the Ma Ba Tha (the Association of Protection of Race and Religion), use multiple social media accounts and digital communication technologies to communicate with their followers directly, frequently bypassing the filter of journalistic or media intervention. Their rhetoric blames the Muslim religion for economic and social instability within the region, and portrays Muslim people as a threat to the Buddhist majority’s physical, spiritual, and social safety.2 Justifications of violence and persecution are based on highly selective readings of Buddhist religious texts as well as sweeping generalizations based on dogmatic interpretations of the same.

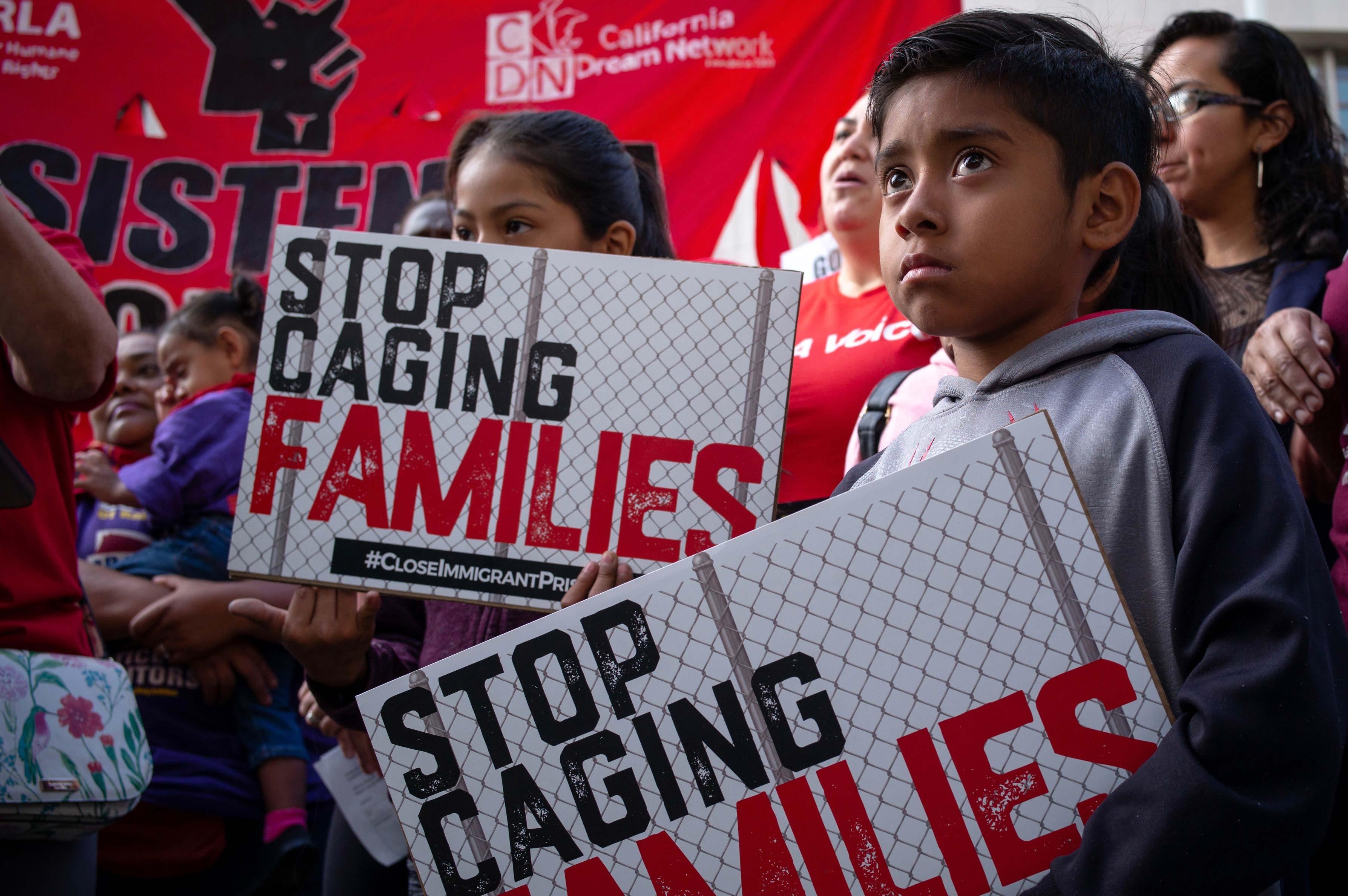

Protest against US Attorney General Jeff Sessions and the Trump administration’s policies, Federal Courthouse in Los Angeles, June 2018. Photo by David Crane, Daily News/SCNG

Similarly, in response to the public outcry against the separation of families by ICE at the US/Mexico border, Attorney General Jeff Sessions referenced a biblical passage (Romans 13) to justify the governmental policy in Fort Wayne, Indiana on June 4, 2018. The White House Press Secretary, when asked to explain Sessions’ use of Christianity to justify the separation of families and isolation of children in cages, responded on June 14 that, “[she] can say that it is very biblical to enforce the law. That is actually repeated a number of times throughout the Bible. It’s a moral policy to follow and enforce the law.” President Trump uses social media extensively as his active presence on Twitter demonstrates, while he repeatedly avoids direct engagement with the press, including his absence from the White House’s Correspondents’ Association dinner—the first president in 36 years not to attend.

Dehumanization

The dehumanization of the Rohingya minority—referred to as a “dehumanizing apartheid” by Amnesty International—is apparent in the above-mentioned instances of political and religious discrimination. However, in addition to this state-sponsored, institutionalized discrimination and violence, Buddhist fundamentalists use interpretations of religious doctrine to identify the minority population as literally non-human, as physical manifestations of demons and hell beings, and as reincarnations of poisonous snakes and insects.3 By stripping the Rohingya of their humanity, one renders the question of genocide moot. Rather than engaging in the systematic eradication of an entire population, one is merely conducting effective ‘pest control’.

Justifications of violence and persecution are based on highly selective readings of... religious texts as well as sweeping generalizations based on dogmatic interpretations of the same.

Similarly, Trump’s comments that members of the Mara Salvatruch (MS-13), an international gang of which most members are of South American origin, “…aren’t people…are animals” was met with public outcry and derision. Populist figures defending this dehumanizing rhetoric attempted to contextualize the comment through descriptions of the MS-13’s legal infractions, but the precise reference to a population of human beings as literally not human remains. This terminology is not uncommon for Trump, echoing his description of South American and Mexican gang members as well as a terror suspect from Uzbekistan as animals during his 2016 campaign.

The discrimination and violence against the Rohingya people, though expressed through a trifecta of political, religious, and human othering, results from the same chauvinist dualism that forms a central characteristic of many contemporary societies, and is expressed and expanded through a similar rhetoric across the globe. Anti-immigrant language is widespread in the current political climates of Brexit in the UK, Trump’s platform in the US, and the growing Right wing movements across continental Europe. At its core, the racial and religious bias against the Muslim minority of Myanmar is a fundamentalist response to the material concerns of an economically vulnerable society in the face of a recent regime change. Less clear, however, is how a supposedly socially stable and economically thriving country such as the US, as well as the many nations of Europe, can justify such explicit and politically sanctioned biases.

1. Donald Trump, Immigration Roundtable Discussion in California, May 16, 2018.

2. Whilst the MaBaTha was officially disbanded by the State Sangha Maha Nayaka Committee, a government-appointed body of Buddhist monastics, in May, 2017, members announced their successor organization, The Dhamma Vamsanurakkhita Association, and the Buddha Dhamma Parahita Foundation. The former was formed with the goal to establish a political party and enter the national 2020 election. The latter was formed with the understanding that “we still have to achieve our goal. If there are obstacles on our route to get there, we will request that they be removed… And if they will block us from all sides, we will step on them. So that we have to be strong.” (Frontier Myanmar 2017).

3. “Rohingya Recount Atrocities: ‘They Threw my Baby into a Fire’.” The New York Times, October 11, 2017:

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/11/world/asia/rohingya-myanmar-atrocitie....