Nutrition, Human Rights, and the Sustainable Development Goals

archive

Nutrition, Human Rights, and the Sustainable Development Goals

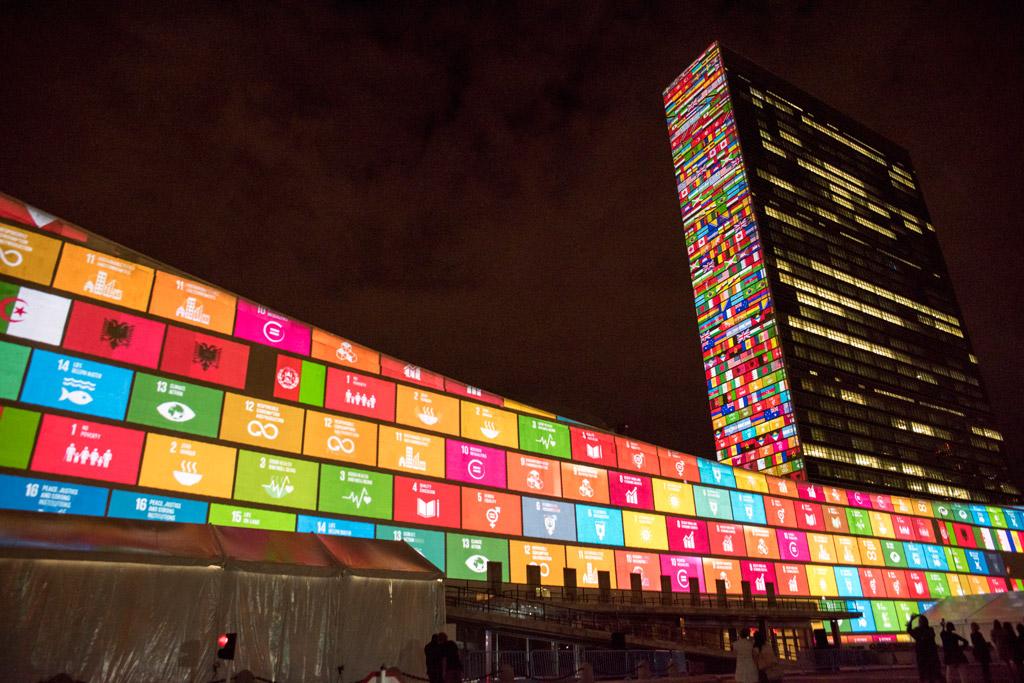

In September 2015, 170 world leaders gathered at the UN Sustainable Development Summit in New York to adopt a 2030 Agenda. The new Agenda covers a broad set of 17 Goals and 167 targets and will serve as the overall framework to guide global and national development action for the next 15 years. The SDGs are universal, transformative, comprehensive, and inclusive.

If we evaluate the SDGs from the perspective of nutrition policies, we notice that nutrition is relevant to all 17 goals. As with all SDGs, nutrition also has a universal character. Without achieving nutrition targets, development policies cannot be successful. The present burden of malnutrition on public health and the national budget has become staggering. At the ICN2, world leaders recognized that a key action for improving nutrition governance is to anchor nutrition targets in the SDGs. While Goal #2 explicitly references “nutrition” (“end hunger, achieve food security, improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture”) and Goal # 3 refers to noncommunicable diseases, nutrition is arguably “interwoven” in relation to all 17 SDGs, as at least 50 of the indicators set forth in the 17 SDGs pertain to nutrition.

The root causes of malnutrition are more complex than the lack of sufficient and adequate food, reflecting as they do a variety of interrelated conditions addressed in the SDGs with respect to health, care, education, sanitation and hygiene, access to resources, environmental degradation, climate change and women’s empowerment. All of these conditions are directly related to development policies. The underlying reality is this: the SDGs cannot be achieved without special attention to nutrition, and the nutrition goals cannot be met without the fulfillment of other SDGs.

Despite the potential success of the SDGs on account of their inclusion of nutrition (in contrast to the antecedent Millennium Development Goals [MDGs]), they still arguably fail to establish a framework that will facilitate the development of sustainable food systems—something which is crucial in the fight against malnutrition. Moreover, some SDG targets lack the focus to enable effective implementation, and a number are not quantified. Many targets are associated with several goals, and some goals and targets may be in conflict with one another. Action to meet one target could have unintended consequences for others if the pursuit of all is not coordinated. Among the 169 targets, only one is dedicated specifically to nutrition; and obesity is not even mentioned. So the indefiniteness of the SDG framework seems to create gaps between the ambition of the goals and the likely performance of states, which gives cause for concern.

The underlying reality is this: the SDGs cannot be achieved without special attention to nutrition, and the nutrition goals cannot be met without the fulfillment of other SDGs.

Furthermore, the lack of an effective accountability and monitoring system is a major obstacle to realizing the SDGs. Voluntary national reporting and reviewing mechanisms through the High Level Political Forum of the UN General Assembly are unlikely to be effective enough to reach the nutrition targets in a timely and sufficiently thorough fashion. The multisectoral nature of nutrition, its long-term impact on human rights and development, and the invisibility of some of its consequences together make accountability a complex and difficult challenge. Meeting such a challenge requires a clear understanding of data collection. This calls for an understanding what is needed to improve nutrition coverage, as well as developing a systematic tracking system for monitoring investment and accountability at country and global levels.

Although significant progress has occurred vis-à-vis the Millennium Development Goals, the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals still avoid directly articulating a human-rights-based approach. We cannot find anywhere in the text of the SDGs a direct affirmation of the “right to adequate food,” or language imposing on states the duty to “respect, protect, and fulfill” human rights, despite the fact earlier noted that all 17 goals are directly or indirectly relevant to the fulfilling the 2030 Agenda for the Sustainable Development Goals.

Overcoming barriers in the “Decade of Nutrition”?

It is true that even if the human rights approach to nutrition were recognized, several barriers would still stand in the way of the adoption of effective nutrition policies and their implementation in pursuit of the various targets. At the height of the global food price crises in 2008, The Lancet Series on Maternal and Child Undernutrition warned that the international nutrition system was fragmented, dysfunctional and desperately in need of reform. Since then, significant initiatives have taken place at the global level. On April 1, 2016, following the recommendation of the ICN2, the UN general Assembly declared the Decade of Action on Nutrition that will run from 2016 to 2025. The Decade presents a unique opportunity to centralize globally agreed targets, align actors around implementation, and address the shortcomings identified in the current forms of nutrition governance. While ambitious targets have been set to ensure the global governance of nutrition, much more is needed to meet the challenge of providing each person with enough nutritious food to live a healthy and productive life, while at the same time protecting the environment and natural resources, including with regard to climate change.

The ICN2 Rome Declaration on Nutrition acknowledged that “current food systems are being increasingly challenged to provide adequate, safe and diversified and nutrient-rich food for all that contribute to healthy diets due to, inter alia, constraints posed by resource scarcity and environmental degradation, as well as by unsustainable production and consumption patterns, food losses and waste, and unbalanced distribution.”

Starting from the observation of the ICN2, the first barrier is the industrial food systems, including production, processing, transport and consumption of food, that are currently dominant in many parts of the world. Food systems have a direct impact on overall diet and in determining what food is available in the market place. Industrial food systems focus on increasing production and maximizing efficiency at the lowest possible economic (and consumer) cost. This type of system relies on industrialized agriculture, including mono-cropping and factory farming, industrial food processing, mass distribution, and marketing. Due to considerations of affordability, availability and palatability, as well as marketing and promotion strategies, food produced from industrialized food systems constitutes a significant portion of global food sales. The adverse impact of industrial food systems on nutrition and public health is widely acknowledged. It is now obvious that excessive food production neither eliminates hunger nor remedies malnutrition. Removing these barriers depends on the appropriate transformation of current food systems into “nutrition-sensitive” food systems. Reflecting the various conditions of specific countries, nutrition sensitive food systems need to be diverse, but the general principles should be sensitive to global nutrition policies and the human rights approach that gives a high priority to nutritionally deprived groups and vulnerable peoples.

The second barrier is a set of factors relating to political, environmental and socioeconomic conditions that have direct and indirect impacts on nutrition in any given society. These conditions include economic development without inclusive growth; population increase, poverty as well as vertical and horizontal inequality; rural urban migration and urbanization; trade and investment policies as well as economic globalization; equal access to natural resources, sustainable resource management, environmental degradation, and climate change.

...nutrition sensitive food systems need to be diverse, but the general principles should be sensitive to global nutrition policies and the human rights approach that gives a high priority to nutritionally deprived groups and vulnerable peoples.

These conditions are interrelated and give rise to negative or positive effects on nutrition depending on policy interventions. Therefore each country should create a “national master plan for good nutrition.” Addressing global nutrition challenges and ensuring that every individual is guaranteed a right to nutrition requires significant reforms in several areas: agriculture, education, health, social protection, water, sanitation and hygiene, gender, trade relations, socioeconomic conditions, environmental degradation, and climate change.

To meet the Decade of Nutrition and 2030 Sustainable Development targets, political will is vital first and foremost. National governments should take these global targets seriously and dedicate substantive financial resources to reaching the targets. Governments should also establish effective, transparent, and independent accountability mechanisms to follow up and review the progress and detect obstacles. Without such monitoring mechanisms and financial resources, there will be little progress, and few nutrition targets will be reached. Needless to say, effective monitoring and accountability systems, as well as inclusive decision-making processes, would be realized if a human-rights-based approach were to be credibly applied to nutrition policies.

This article, the second in a two-part series, is adapted from Dr. Elver’s Foreword to Good Nutrition: Perspectives for the 21st Century. M. Eggersdorf, K. Kraemer, J.B. Cordano et al, eds. Basel: S. Karger, 2016.