Magic of Public Imagination: Transcending Public Evil

archive

Magic of Public Imagination: Transcending Public Evil

There was a moment on July 7, 2015 in the Mother Emmanuel African Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, when Barack Obama seized his people's political imagination as he had done in his early days in politics. He stood tall at the lectern, surrounded by black religious leaders in robes, to give the eulogy for the Reverend Clementa Pinckney and the seven others gunned down during a bible study at their church. The President took a long pause, leaned forward, and began to sing alone, the 18th century Christian hymn, Amazing Grace, written by the slave-trader turned Christian minister John Newton. Visibly stunned, then smiling broadly, the priests in unison began to sing along. Obama then named each victim, following each name with the words, “XX…found that grace, through the example of his/her life.”

Obama himself is a man of grace. But in these distracted political times he has often struggled for his hold on public imagination—the foundation of people’s political empowerment. On that July day he reminded me of another powerful moment caught forever on film, when another great American leader sang on another continent, and seized the imagination of another world.

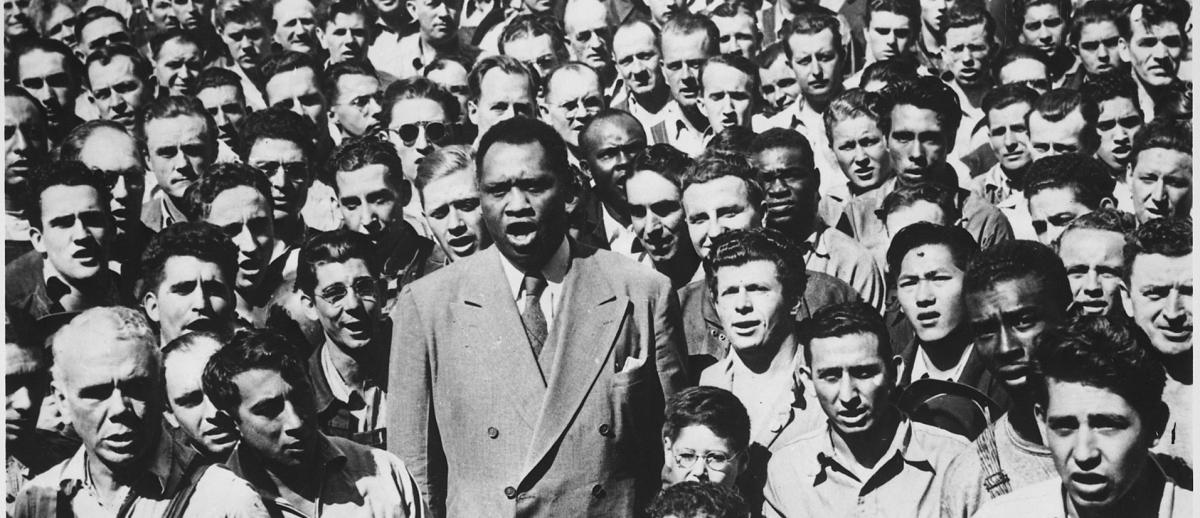

Half a century ago, in the radical political days after World War II, the black singer and actor Paul Robeson visited Scotland, invited by the Scottish branch of the National Union of Mineworkers to give a concert in a large hall in Edinburgh. (Robeson’s history with the NUM dated back to the late 1920s when he visited Welsh miners and went on their hunger marches in 1927 and 1928.) Before the official Scottish event Robeson visited a colliery, lunched in the miners' canteen, and then, impromptu, he rose to his feet and began to sing The Ballad of Joe Hill in the middle of a rapt room of white working class men. Hill was a legendary Swedish/American union organizer, who was executed in 1915 on a framed murder charge. In a parting telegram to a fellow union leader he wrote, “Goodbye, Bill, I die like a true blue rebel. Don't waste any time mourning. Organize!”

In those postwar years Robeson became the mentor to another American whose art and whose words have fired political imagination across the world for decades, and still do. Harry Belafonte was a janitor’s assistant, a high school dropout in New York feeling a sense of loss. Wartime service in the Pacific had shown him a different life, but the post-war US showed him only white oppression. A chance meeting with Robeson during Belafonte’s first ever visit to a theatre changed his life. “Paul Robeson set my course, by his intellect and courage, gave me a purpose in life, showed me the value of profound thought, showed me global commonality.”

Robeson, a victim of McCarthyism in 1950s America, was blacklisted and his artistic career shattered. But Belafonte went on to become the most articulate of global citizens, fired by the power of art and words to feed imagination. He has plunged forward with fearless resistance to oppression wherever it is found. He was a luminary of the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa, and at home in the most dangerous years of the US civil rights movement. Inevitably, he was one of the sponsors of the Washington women’s protest march on Donald Trump’s first day as president.

A decade earlier Belafonte had protested another president’s political choices and referred to George W. Bush as “the greatest terrorist in the world” for launching the war in Iraq. He went on to criticize the powerful African-American members of the Bush administration, General Colin Powell and National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice, referring to them as “house slaves.” Belafonte resisted intense media pressure and steadfastly refused to apologize. To Powell and Rice, he said, “you are serving those who continue to design our oppression.”

Obama in that church in Charleston was a man at home, and he seized the moment of raw emotion to speak from his heart about his people’s “systematic oppression and racial subjugation,” and of how the killer’s action had been “a means of control, a way to terrorize and oppress,” and “an act that he presumed would deepen divisions that trace back to our nation's original sin.”

Obama did not see then (though surely he should have as the years passed) that Guantanamo was not an episode but an era. And the lack of accountability for Guantanamo and the tortures, renditions and secret prisons which grew up around it, changed Americans themselves...

These were wonderful powerful words, and words that Obama could have spoken about the dark anti-Muslim world of torture, dehumanization and fear which he inherited from his two Bush predecessors, and associates such as Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney. President Obama thought he could close Guantanamo and end a shameful episode. But his early decision to be a president who looked forward, not back, was a failure of his own political imagination. His Justice Department knew well that the law had been broken in the Bush years, but was itself on the same trajectory in arguing before the courts in cases involving prisoners and torture. Obama did not see then (though surely he should have as the years passed) that Guantanamo was not an episode but an era. And the lack of accountability for Guantanamo and the tortures, renditions and secret prisons which grew up around it, changed Americans themselves, changed much of the world’s attitude to America, and allowed the unraveling of the post-World War II international architecture of idealism in the Geneva Conventions and other United Nations conventions.

“Humankind cannot bear very much reality,” T. S. Elliot wrote so memorably. In these torture years many thousands of Americans including politicians, doctors, psychologists, lawyers, soldiers, guards, interrogators have been witnesses, participants, and instigators of unspeakable cruelty and degradation on Muslim men. How did they live with their reality? Denial, lies, false justifications, military and institutional discipline, and media complacency kept most of these people inside the web of numbed acceptance. (The whistle blowers—from Thomas Drake and John Kiriakou to Chelsea Manning—fired imagination across the world, but paid a very high price, including on Obama’s watch.)

The first terrible photographs from Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq showed the world indelible images of US torture, which deviated starkly from the expressed principles behind the “war on terror.” The Bush administration’s attempt to pin responsibility for Abu Ghraib on “a few bad apples”—junior soldiers—soon fell apart and there was initially shocked reaction from the media and others. Calls for the resignation of Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld came from across the board. In May 2004 former Vice President Al Gore called also for the resignations of CIA director George Tenet, National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice, Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz, and senior Defense officials Stephen Cambone and Douglas Feith.

...How did they live with their reality? Denial, lies, false justifications, military and institutional discipline, and media complacency kept most of these people inside the web of numbed acceptance.

But, none of this shaming happened. Cynicism was fed and torture was normalized in the public mind. Two years later even more Abu Ghraib images were published. In December 2015 the long awaited Senate report on US torture in the secret CIA black sites revealed years of even more degrading practices. But the airwaves were filled with Dick Cheney assuring the US that it had all been necessary, even worthwhile, and that he would certainly do it all again.

During more than a decade of the “war on terror” there was a progressive shutdown of public imagination about the enormity of this illegal and immoral reality, in which the US had many complicit partners in Europe and the Middle Eastern. We know now that denial won the battle of public opinion and brought to the White House a man locked in his own random certainties, and someone who shares none of the attributes that Robeson showed Belafonte: “intellect and courage… a purpose in life… the value of profound thought… global commonality.”

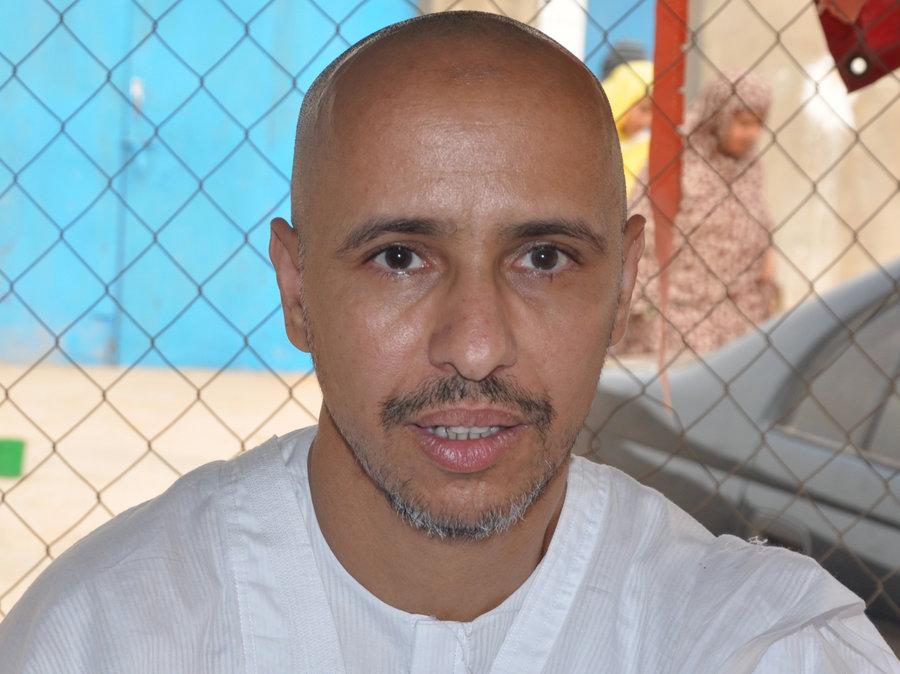

Mohamadou Ould Slahi. Credit: Getty Images

From Guantanamo Bay prison, of all places, came a man with just this array of qualities, a Mauretanian, Mohamadou Ould Slahi, detained without charge for 14 years. His book, Guantanamo Diary, was written in an isolation cell after he had been broken by torture in Donald Rumsfeld’s Special Interrogation Plan. This book is the antidote to numbness, to forgetting, to cynicism, to loss of humanity. It is a gift to our public imagination. The fine editor of Slahi’s book, American writer Larry Siems, describes the author, whom he was never allowed to contact in Guantanamo, as “curious, forgiving, social.”

Siems writes, “he has the qualities I value most in a writer: a moving sense of beauty and a sharp sense of irony. He has a fantastic sense of humor.” The book is written so vividly that it is hard to believe English is Slahi’s fourth language and one he mostly learned while in custody, despite so often being completely deprived of human contact by his American jailers.

Slahi’s warm personality, his intelligence, and his vivid descriptions belie the grimness of his material. It took nearly a decade of battles by his tireless lawyers to get the manuscript cleared by the US authorities—albeit with 2,500 black lines of redacted names and whole passages scarring the pages. It has been published in 26 countries and 23 languages and made the New York Times best-seller list. There you see the power to set alight public imagination—and renew an empathy that had been dulled to the point of extinction.

Last autumn, one year after it was published and Slahi became known around the world, he was released home to Africa. I hope Mr. Obama has time now to read this book and discover a man of grace who survived the worst of his presidential era.