Barriers to New Thinking about Internationalization in Higher Education

archive

Barriers to New Thinking about Internationalization in Higher Education

The idea of internationalization is now a key objective in the strategic plans of most universities and colleges around the world. The policy significance of internationalization is often linked to the challenges and opportunities associated with the contemporary processes of globalization. Internationalization is portrayed both as an expression of and response to these processes. An internationalized approach to teaching and learning is for example considered essential to prepare students to meet the shifting requirements of work and labor processes transformed by digital technologies and global capitalism.

The discourse of internationalization in higher education is grounded in a range of new answers to the old question of what counts as knowledge that is worthwhile. Invariably these answers are now driven by various commercial concerns. With the growing recognition of the emergent transnational links between people that enable them to collaborate across cultural and national boundaries, universities now attach much importance to cross-cultural dialogue and understanding. Yet many institutions invariably interpret these important concepts in market terms, as necessary requirements of the global economy.

Shifting Paradigms of Internationalization

While this policy discourse of internationalization may be relatively recent, there is nothing new about its practices. From the very beginning, academies of higher learning encouraged exchange of ideas across national and cultural boundaries. In the colonial period, for example, global mobility of scholars was encouraged in order to realize the political interests of the colonizers, producing a local administrative class that could be relied upon to realize colonial interests. An asymmetry of power was simply assumed, with higher education becoming a site for the reproduction of social differentiations, both within and across borders.

After the colonies achieved independence, internationalization of higher education served a new purpose, of providing development assistance in the form of technical knowledge and skills that were needed by the newly independent countries to pursue their objectives of nation building. Yet while this ‘developmentalist’ discourse had the benign appearance of international cooperation, it presupposed patterns of global inequalities that were seldom questioned. The West was assumed to be the harbinger of the most worthwhile knowledge, imparted selectively to the students of the Rest.

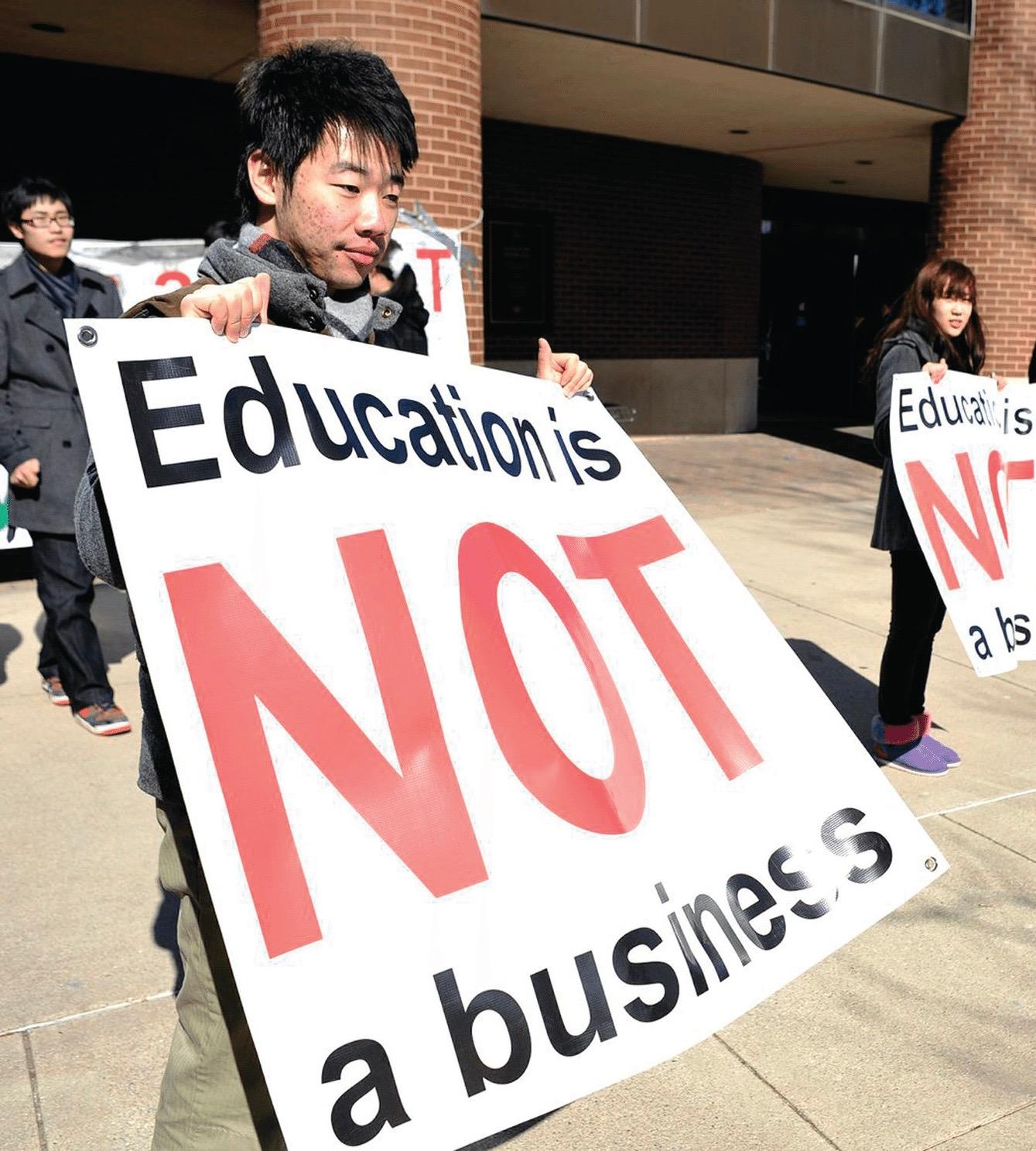

Over the past few decades, a new discourse of internationalization of higher education has become dominant, framed within the neoliberal logic of the market. It is grounded in considerations of trade and revenue generation. While older justifications of internationalization have not entirely disappeared, they have been rearticulated by a market rationality that now defines the value of international experiences and exchange. International students are seen as a source of revenue for the universities, and a highly elaborate administrative technology has been created for recruiting them. Many universities have become totally reliant on this source of income for their survival.

This view of internationalization has of course not been without its critics.1 In commercial terms, the risks associated with an excessive reliance on income from international students have been noted, especially as various national systems begin to develop their own universities, and as the geopolitics of global mobility becomes uncertain and unpredictable. Equally, this focus on fee-paying international students favors those who are already privileged, the transnational elite. It reproduces patterns of global inequality, since the movement of these students is largely from the Rest to the West, while most cases of educational tourism and voyeurism are mostly in the opposite direction.

Attempts are therefore being made to craft a new discourse of internationalization that does not abandon the focus on international students but rather supplements it with the notion of transnational collaborations in both teaching and research. Of course, scholars have a whole range of reasons for wanting to collaborate with colleagues located in other parts of the world. These include shared research interests and curiosity to learn more about other cultures and languages. Personal friendships and diaspora networks also drive scholars to collaborate across national boundaries.

While older justifications of internationalization have not entirely disappeared, they have been rearticulated by a market rationality that now defines the value of international experiences and exchange.

While these personal motivations vary, in terms of attempts to broaden the definition of internationalization, the policy discourse of academic collaboration remains tied to market rationality. A globally networked economy, it is argued, implies the need for institutions of higher education to collaborate with each other, especially in the production, dissemination, and commercialization of new knowledge. Digital information technology, it is noted, now permits extensive forms of collaboration that have potentially transformative consequences for economy and society. The generation of wealth and national economic development is assumed to be heavily dependent on global networks, on the capacity to cooperate across national borders.

Collaboration: Benefits and Hurdles

It is suggested that transnational academic collaborations have the potential to build trust, mutual affection, and understanding across communities. Such collaborations are assumed to be a mechanism for joint research to address contentious and shared issues, and even mitigate the consequences of terrible events, such as fires, floods, and flu viruses. At the same time, collaboration is considered necessary for data to be collected, consolidated, and compared, allowing rapid transfer of information and expertise to places where it is needed. It is helpful also in solving problems around such global issues as climate change, international trade, and security.

For universities, transnational collaboration represents a cost-effective way of supporting the infrastructure needs of staff, especially in capital-intensive fields, where an institution’s own capabilities may have gaps or lack adequate scale. It enables them to access expertise, equipment, datasets, research subjects, or environments that might not exist at the local level. In recent years, transnational collaboration has been used by universities as a mechanism for benchmarking performance and determining which researchers are doing internationally significant work. Increasingly it has also been viewed as a measure of global reputation of universities, assumed to be necessary for enhancing their global ranking.

Universities around the world are thus beginning to regard transnational collaboration as an important new dimension of their policies of internationalization. However, in developing robust and meaningful forms of collaboration they encounter numerous obstacles. These obstacles can be both institutional and cultural. At the institutional level, contentions over resources or capabilities can often be a source of major difficulties, as indeed can be the inadequate support provided by government agencies. Bureaucratic red tape, such as complex and expensive visa regimes, can inevitably frustrate research collaborators and derail projects already begun.

At the cultural level, differing research and academic traditions can generate contrasting expectations among researchers and institutions. Lack of understanding and continuing interest, as well as inadequate familiarity with relevant cultural traditions and language, can also put strain on research relationships, both at the initial development stage and through the course of implementation. The principle of reciprocity is considered important in achieving sustainable and robust forms of collaboration, but such reciprocity is difficult to achieve when the levels of expertise and research infrastructure vary.

In recent years, transnational collaboration has been used by universities as a mechanism for benchmarking performance and determining which researchers are doing internationally significant work.

Leading universities in countries such as Australia, Britain, and the United States, prefer therefore to collaborate only with highly ranked universities. Meanwhile, in the Global South, top universities in places like India, Indonesia, and China are often inundated with requests to collaborate, while poorer universities, where collaboration can often result in genuine and far-reaching benefits, are mostly ignored. Many universities in the Global South are also understandably weary of the asymmetries of power and knowledge, grounded in colonial and neo-colonial histories, and reinforced by skewed patterns of funding and misunderstandings over motivation.

As serious as these issues are, perhaps the most serious barrier to forging and sustaining productive forms of transnational academic collaborations as part of a new understanding of internationalization in universities relates to the fact that their imagination of what might be possible is now often shaped by commercial considerations, rather than cultural or educational ones. Much of the policy work that higher education institutions do is now trapped within the dictates of market rationality. While many researchers begin with the best-intentioned conversations about the benefits of collaboration, they are invariably stopped in their tracks by difficult and contentious issues regarding such commercial concerns as intellectual property and ownership. The growing embrace of market rationality thus often prevents them from doing good things.

Hartmann, E. (2011) The Internationalisation of Higher Education, London: Routledge.

Altbach, P. (2016) Global Perspectives of Higher Education, Amsterdam: Springer.