Neoliberal Tourism Development: The Case of ‘Tourism Conservation Enterprises’ in Kenya’s Maasailand

archive

A main building of Tawi Lodge in Kilitome Conservancy; February 2012. (Photo: Toshio Meguro)

Neoliberal Tourism Development: The Case of ‘Tourism Conservation Enterprises’ in Kenya’s Maasailand

Kenya is home to vast savannah and diverse wildlife. For generations, its ‘wild’ nature has attracted admirers and travellers from around the world and since the colonial period its government has promoted both wildlife tourism and conservation. Since the 1990s, as community-based conservation became the new paradigm,1 local participation, benefit-sharing, and collective decision-making have gained greater importance. Today, tourism tends to be viewed as panacea, especially in policy circles. The expectation is that tourism will help realize various development goals all at once.2 With regard to community participation, however, there is an opinion that communities often lack business skills and access to the transnational tourism market to run a tourism business profitably,”3 suggesting an approach where tourism is managed by private entrepreneurs without the involvement of locals. Such an approach is based on neoliberal assumptions that place full confidence in the market economy and private enterprises, rather than public and community sectors. Reflective of this approach is a ‘tourism conservation enterprises’ project in the Amboseli region in southern Kenya, which was launched in 2007 by the African Wildlife Foundation (AWF), an international NGO working in Africa. Although the project achieved its conservation objectives, the local partners had very different assessments of the objectives, practices, and outcomes of the initiative. Rather than a panacea, tourism development proved to be a mixed blessing for local communities while nevertheless advancing the conservation interests of the NGO.

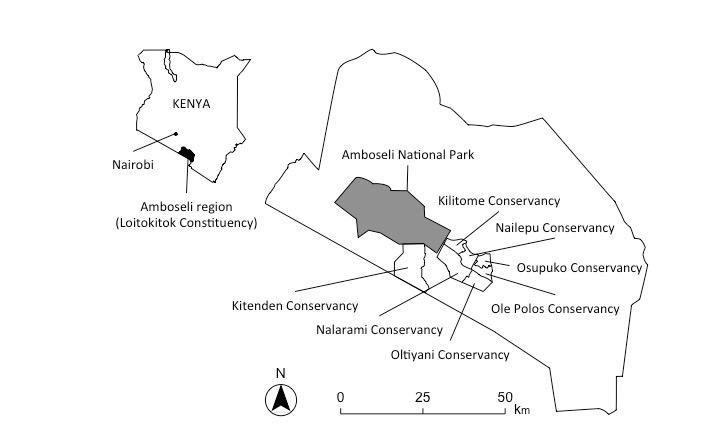

The Amboseli region, or Loitokitok Constituency, is home to a group of Maasai people as well as diverse wildlife (Figure 1). I have conducted sociological field research in this area since 2005. My research has focused on the local Maasai communities’ reactions to development and conservation projects initiated by outsiders.4 With its framing of the African Wildlife Foundation’s tourism conservation enterprises (TCE) as a new neoliberal, community-based project,5 this article centers on the following: What have been the TCE’s outcomes and what have local communities’ responses to it been? And, does the neoliberal idea foster positive outcomes for locals involved in the TCE project?

Processes and outcomes of ‘Tourism Conservation Enterprises’ in Amboseli

The tourism conservation enterprises project can be defined as “a commercial activity which generates economic benefits in a way that supports the attainment of a conservation objective.6 The AWF is a key initiator and go-between. It encourages local communities to amalgamate their lands and to establish wildlife protected areas known as ‘conservancies’. The organization then acts as an intermediary between local landowners (that is, members of conservancies) and private investors: the former agree not to use natural resources inside the conservancy in order to enable the latter to develop tourism there. In return, the latter pay land-use fees and provide other benefits (e.g. employment and bursaries) to the locals. For its part, the AWF secures funds from international donors and conducts conservation operations such as monitoring wildlife populations and combatting illicit activities like poaching.

Figure 1: International tourists taking pictures of elephants in Amboseli National Park. (Photo: Toshio Meguro)

In the Amboseli, the AWF held its first meeting in July 2007 with local Maasai communities who owned a parcel of land to the east of the Amboseli National Park. The National Park has an area of 390 km2, and is a popular tourist destination known for its elephant herds and scenic views of Mt. Kilimanjaro. I was able to attend the meeting, and observed the AWF program manager highlighting the economic significance of wildlife and the importance for local Maasai to set aside their lands for conservation. The manager also suggested that once conservancies were established, the landowners could enjoy the benefits arising from tourism. The local people agreed to the proposal. By June 2013, more than 400 Maasai approved the idea and established six conservancies: Osupuko, Kilitome, Nailepu, Oltiyani, Ole Polos, and Nalarami (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Map of the Amboseli region

One successful outcome of this initiative is the Kilitome Conservancy, which lies east of the Park and was created in November 2008 with 99 members. Two years later the Tawi Lodge was opened inside the conservancy, which is now generating a land-use fee of more than US$300 per capita per year for its members, which adds up to more than US $40,000 annually for the group as a whole.7 Kilitome Conservancy is featured on the AWF’s website as “a shining example of the conservation and socioeconomic gains that can be achieved for all when a private company proactively partners with the AWF and local communities.”8

However, the AWF did not meet the members’ expectations completely. In my field research, all members I asked said that they assumed that as part of the agreement, the AWF would bring tourism companies to build lodges and pay revenue to all local communities. They thought it was the AWF’s obligation, but the AWF project manager told me that in fact he would not try to find private investors for the rest because it was difficult to develop tourism facilities in all conservancies because of tough competition in the area. Consequently, only Kilitome Conservancy saw tourism development while the other five conservancies did not.

Rather than a panacea, tourism development proved to be a mixed blessing for local communities while nevertheless advancing the conservation interests of the NGO.

Diverse understandings of ‘failure’

The TCE project in the Amboseli region failed to deliver on its key promise of tourism development, but it does not mean that those concerned evaluated the project to be meaningless. Once the six conservancies were established, the AWF stopped having meetings with their members and turned their attention to Maasai communities in an adjacent area to set up another, the Kitenden Conservancy (see Figure 2). The AWF staff went through similar steps there: They explained to local Maasai landowners that the establishment of a conservancy would lead to tourism development. However, once the agreement was reached in 2013, it was introduced as a “land lease program”9 without any mention of tourism. Considering that the AWF’s main mission is wildlife and habitat conservation,10 and the establishment of conservancies contributes to that mission, it would appear that the discourse of neoliberal tourism development enables the AWF to obtain global funds and secure local participation, but it does not necessarily result in tourism development. Instead, AWF seems to use the promise of tourism as a means to secure agreements that support its ultimate goal of conservation.

Scenery of the Osupuko Conservancy. There is no tourism development here, and local people, livestock, and wildlife continue to use it. (Photo: Toshio Meguro)

In as far as there has been no tourism development on their land, local communities have considered the tourism conservation enterprises a failure, but still beneficial. That is, even though many conservancy members were unhappy that the AWF did not help develop tourism as promised and complained about the size of their land-use fee (Ksh. 30,000/year, or about US$ 300-400 per member), almost all members renewed their contracts. The chairman of one conservancy explained the reason for this: although he was not happy with the outcome, the land was remote and non-arable with no other means to yield a profit. Thus, it was better to renew the contract and earn some income than none at all.

Here it must be noted that the members did not naively expect the project to produce stellar results, nor did they necessarily intend to comply with the contracts. The chairman stated that if they had had a choice, they would have opted for other profitable ventures even if that meant contravening the contract and reversing conservation gains. To them, a conservancy was just one among numerous land-use options which could be chosen and abandoned, depending on the situation. From the perspective of the local people, the failing tourism conservation enterprises project is profitable inasmuch as it brings in monetary income. Like the AWF they assessed the project positively, but their criterion is different from the AWF.

local communities have considered the tourism conservation enterprises a failure, but still beneficial.

Conclusion

Today, tourism is expected to contribute to Africa’s development in the neoliberal way, and conservation NGOs trumpet their tourism development initiatives globally. This article shows that tourism development by large private enterprises is not always successful because of the entry barriers that stiff competition can produce. In other words, tourism is not a panacea at all times. Second, the TCE project’s failure is neither unexpected nor derailing for the parties concerned. Some, such as the AWF, may use a neoliberal tourism development idea as a pretext to achieve other ends (such as conservation), and others, such as local communities, may use it as a temporary stop-gap measure. To these groups, projects of this kind are meaningful even if they do not achieve their original goals. What is common to those involved in the TCE project in the Amboseli region is a flexible attitude to tourism. They expected tourism to bring certain benefits, but at the same time, they were aware of the possibility that tourism development can end in failure. For them, in other words, tourism is not a cure-all but a ‘good enough supplement’. Theirs is a pragmatic attitude: if tourism brings something, they engage with it; if it does not, they abandon it with little hesitation or regret and look for other options.

1. David Western and R. Michael Wright (eds.) (1994) Natural Connections: Perspectives in Community-based Conservation (Washington D.C.: Island Press).

2. Christie, Iain, Eneida Fernandes, Hannah Messerli and Louise Twining-Ward (2014) Tourism in Africa: Harnessing Tourism for Growth and Improved Livelihoods (Washington D.C.: World Bank).

3. Van der Duim, René, Machiel Lamers, and Jakomijn van Wijk (2015) ‘Novel Institutional Arrangement for Tourism, Conservation and Development in Eastern and Southern Africa,’ in René van der Duim, Machiel Lamers and Jakomijn van Wijk (eds.), Institutional Arrangements for Conservation, Development and Tourism in Eastern and Southern Africa: A Dynamic Perspective (New York: Springer), p. 3.

4. Meguro, Toshio (2012) ‘Becoming conservationists, concealing victims: Conflict and positionings of Maasai, regarding wildlife conservation in Kenya,’ African Study Monographs Supplemental Issue 50: 155-172.

5. René van der Duim, Machiel Lamers and Jakomijn van Wijk (eds.) (2015) Institutional Arrangements for Conservation, Development and Tourism in Eastern and Southern Africa: A Dynamic Perspective (New York: Springer).

6. Elliott, Joanna and Daudi Sumba (2011) Conservation Enterprise: What Works, Where and for Whom? (London: International Institute for Environment and Development), p. 7.

7. https://ecotourismkenya.org/eco-rated-facilities/entry/23/ (last accessed: July 23, 2018)

8. https://www.awf.org/projects/tawi-lodge (last accessed: March 1, 2018).

9. AWF (2013) “African Wildlife Foundation’s African Landscape 2013 Issue 3.”

https://www.awf.org/sites/default/files/media/Resources/Technical%20Part... (last accessed: July 2, 2018)

10. https://www.awf.org/ (last accessed: March 1, 2018).