Indigenous Studies in an Era of Global Pandemic

archive

UNC Pembroke student Regan Scott (left), watches Ngarrindjeri elder, Aunty Noreen Kartinyeri during a basket weaving workshop at the 'Ngarrindjeri Photography in the 20th Century' opening reception, hosted by the Swinburne University of Technology in Melbourne, Australia. (Photo courtesy of the author)

Indigenous Studies in an Era of Global Pandemic

In southeastern North Carolina, where I teach American Indian Studies (AIS) at the University of North Carolina Pembroke (UNCP), there’s a palpable feeling in the atmosphere when a hurricane is building: a shift in humidity, increasing atmospheric motion, storm clouds moving in, and—despite the beauty of the initial drama—a sense of dread stemming from uncertainty about the severity of the impending storm. Out of sync with hurricane season this year, UNCP faculty felt the same sort of tension as the first winds of the escalating coronavirus pandemic blew in via email on March 11, announcing that all instruction would transition to digital delivery by March 20, and that students would not be returning after spring break. We braced ourselves. In quick succession, long-scheduled events were suspended, postponed, and cancelled, including the AIS Department’s hosting of the summer global studies program “Indigenous Southeast” with our partner institutions in the International Indigenous Exchange Consortium (IIEC). The storm was upon us, and as I write this in May, global and international studies programs like ours face a future that none of us can envision with certainty.

What faculty members of the IIEC can claim with certainty—based on the two IIEC programs we have already participated in, in Canada and Australia—is the transformative impact of our program on international students in three countries on two continents. The IIEC is the result of an idea hatched with our partner institutions at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon, Canada, and Swinburne University of Technology in Melbourne, Australia, in 2014. Our foundational goal was to create, as we wrote in our original MOU, “a partnership between our institutions that would allow students from each program to engage in community-based learning in different Indigenous contexts around the world.” We envisioned the IIEC being controlled by Indigenous and non-Indigenous faculty at global universities with Indigenous Studies, Native Studies, and/or American Indian Studies programs, schools that served a significant number of Native/Indigenous students, in or with proximity to Native communities.

To our knowledge, the resulting IIEC program is the only one of its kind in existence. Faculty worked together on developing the course for four years before launching the first IIEC study abroad course in 2018 at the University of Saskatchewan. The host university provides curriculum for all participants in that year’s course, which faculty at each school teach separately to their students prior to the travel/study segment of ten to twelve days, at which time everyone gathers at the hosting university. IIEC faculty intentionally discussed bringing between five to seven students from each of our universities, so that travel and group size wouldn’t become too logistically unwieldy. The UNCP undergraduate students who enrolled in the IIEC courses in 2018 and 2019 were Native American and African American though the course is open to all students at all three universities.

During the inaugural IIEC program in Saskatchewan, our activities included camping on Poundmaker Cree First Nation homelands, learning from First Nations knowledge keepers about traditional medicine plants and Indigenous games, and being hosted by the renown Métis elder Maria Campbell—the author of one of our course texts, the groundbreaking autobiography Halfbreed (1973). In Melbourne, we learned about the histories and experiences of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation, attended annual NAIDOC (National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee) events celebrating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, heard yidaki performances, watched a precision boomerang demonstration by Wurundjeri elder Murrundindi, and met kangaroos, wombats, and koalas at the Healesville Sanctuary for indigenous wildlife. As hosts for this summer’s July 2020 IIEC course “Indigenous Southeast” at UNCP, we crafted an itinerary that included learning about Coharie tribal culture from Coharie river keepers and elders, visiting Cherokee and Lumbee traditional farmers, and attending the annual Lumbee Homecoming celebration in the heart of the Lumbee Indian community, among other activities.

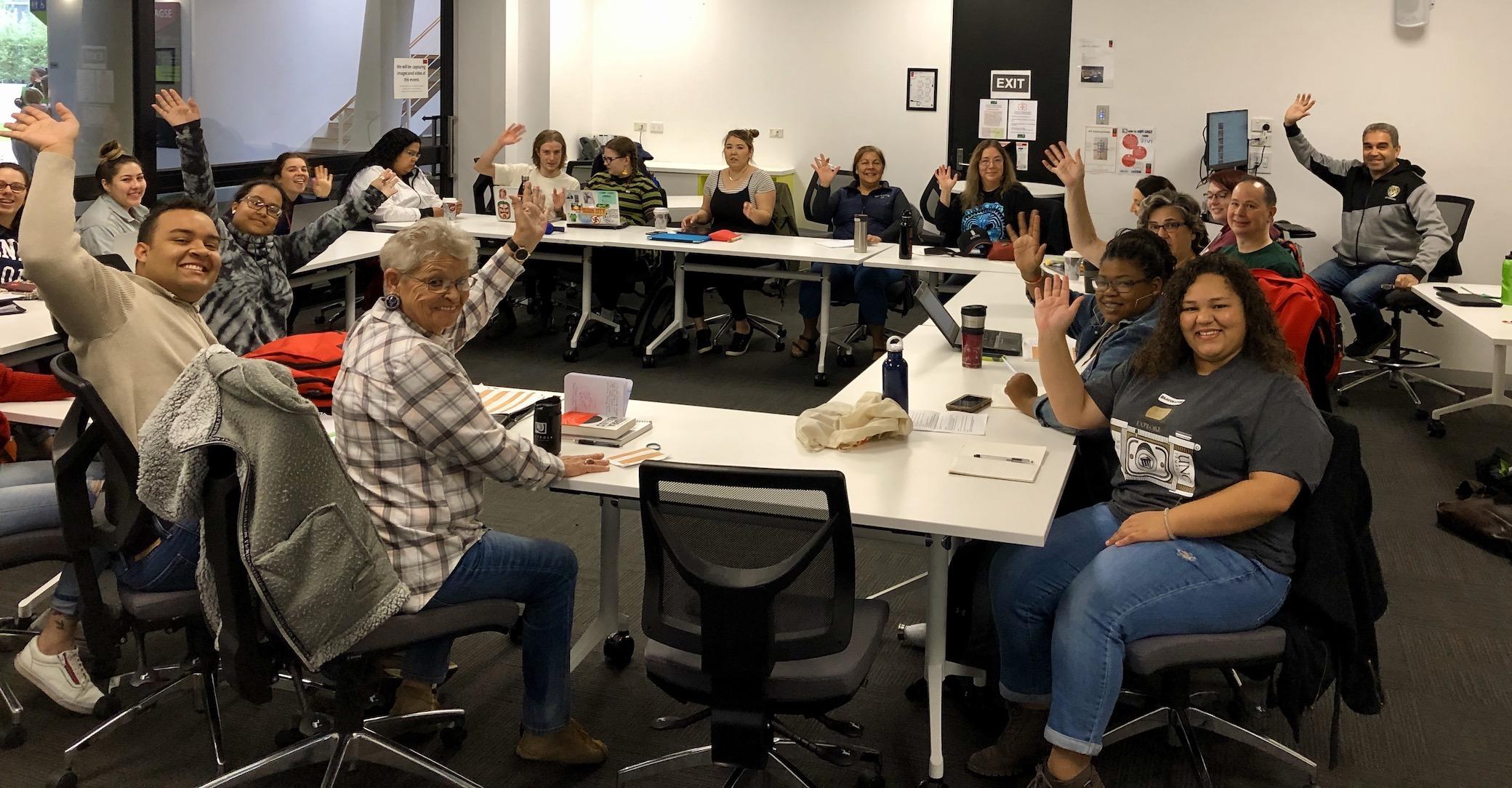

Students and faculty from the University of North Carolina at Pembroke, the University of Saskatchewan, and Swinburne University of Technology gather for a seminar on the Swinburne campus in Melbourne during the IIEC program in 2019. (Photo courtesy of the author)

Research shows that while study abroad offers powerful benefits to all students, it benefits Indigenous students in particular ways. In the article “Native American Student Participation in Study Abroad: An Exploratory Case Study,” the authors explain that even though Native students appreciate opportunities to take study abroad courses, “a convergence of barriers exists” for these students “that highlight the need not only for greater institutional understanding of Native perspectives, but also for institutional promotion of study abroad that incorporates these perspectives” (Stephen Wanger, et al., 139). Barriers include the cost of study abroad, and the fact that Native students are strongly influenced in their decisions to participate by their social support networks of “parents, friends, Native advisers, siblings, [and] tribal members” (140). Faculty in American Indian Studies are well aware of these realities for our Native students at UNCP; we have worked to help generate funds with and for students to participate in IIEC travel study trips and have communicated openly and consistently with students and their families—many of whom have never traveled farther than Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, or have never flown on a plane—about what the travel and global studies experience will be like. Wanger et al. affirm the importance of supportive relationships with teachers and mentors, and advocate for a university culture that provides both encouragement and tangible financial help for Native students to engage in study abroad, saying it yields consistently positive results.

Research shows that while study abroad offers powerful benefits to all students, it benefits Indigenous students in particular ways.

Additional scholarship underscores that place-based and experiential learning powerfully enhances undergraduate student learning. For Indigenous students in their own social and cultural communities, such learning can be especially powerful, as can be the opportunity for Native students to share experiential learning with non-Native allies and intergenerationally with community elders. In their article “Educate to Perpetuate,” Corntassel and Hardbarger recognize that contemporary Indigenous youth are at risk of losing valuable cultural knowledge from elders who have themselves experienced “direct racism and dislocation from cultural practices, land, medicine, knowledge, and traditional lifeways” (87) due to government policies of assimilationist education in boarding and residential schools, forced removals from original homelands, and/or land loss. The authors discuss the ways that “everyday acts of resurgence” within homes and communities, rather than within state-centered institutions and spaces, provide a meaningful framework for reconsidering what Indigenous cultural revitalization looks like. Corntassel and Hardbarger explain how these intimate, informal sites of cultural practice “can challenge colonial systems of power at multiple levels, while being critical sites of education and transformative change”; specifically, they highlight how “‘land-centered literacies’” may serve as “pathways to community resurgence and sustainability” (87).

Freshly picked saskatoon berries on the Poundmaker Cree Nation in Saskatchewan, Canada, during the IIEC program in July 2018. (Photo courtesy of the author)

We witnessed the international connections made by our Native students from North Carolina as they formed enduring bonds with Cree, Métis, Anishinaabe, and Yorta Yorta/Wemba Wemba students during our two IIEC courses. Our students opened themselves to understanding shared stories of original cultural knowledges, languages, and worldviews, the loss or suppression of this knowledge through the processes of colonization, and the resistance, revitalization, and resilience of Indigenous peoples in these locales to maintain and regain meaningful facets of their cultures. In sharing these stories within the embrace of specific Indigenous homelands, enriched by the intensity of direct sensory experience, new insights and memories were indelibly imprinted on students from three countries and seven Native Nations. This summer, it would have been our turn to share similar experiences through the IIEC “Indigenous Southeast” course. For now, we will have to wait.

In this unprecedented historical moment, all of us in higher education can agree on one thing at least: our classrooms and our delivery of instruction going forward will look very different, wherever it takes place. Despite the understandable lack of clarity right now about what international studies programs will look like in the next six, twelve, or twenty-four months, I am choosing to remain optimistic about the long term. This is because you can’t virtually gather with students to pick a ripe saskatoon berry on Cree Nation land with Poundmaker Cree elders; you can’t hold the berries in your palm and eat them straight off the bush, the clean wind blowing your hair across your face, on Zoom. You can’t hold fresh river rushes in your fingers and smell their beautiful sweetness while Ngarrindjeri women elders in Melbourne carefully, patiently guide your fingers as you slowly weave the beginnings of a basket, laughing with you as you struggle, then succeed. Those of us in global studies know that not only can it “never be the same” to run a virtual study abroad course in Melbourne or Saskatoon or Pembroke, it can never even come close. We know that we will stand on the earth in these places again. Yet for the time being, we will have to adjust along with our students, and we will. Indigenous peoples, no strangers to viral pandemics and to rapid, extreme cultural change, serve as my model for strength, resiliency, and gratitude as we all shelter from the current storm, for as long as we must.

________________

Author's note: I would like to acknowledge and thank my faculty collaborators in the IIEC for making this program happen: Dr. Mary Ann Jacobs in the Department of American Indian Studies at The University of North Carolina at Pembroke; Drs. Robert Innes and Winona Wheeler in the Department of Indigenous Studies at the University of Saskatchewan; and Dr. Andrew Peters in the Department of Health, Arts, and Design at Swinburne University of Technology.

Corntassel, Jeff and Tiffanie Hardbarger. “Educate to perpetuate: Land‑based pedagogies and community resurgence.” International Review of Education, vol. 65, 2019, pp. 87–116.

Wanger, Stephen, Robin Minthorn, Kathryn Weinland, Boomer Appleman, Michael James, and Allen Arnold. “Native American Student Participation in Study Abroad: Exploratory Case Study.” American Indian Culture and Research Journal, vol. 36, no. 4, 2012, pp. 127-152.

Further Reading

Roumell, Elizabeth A. “Experience and Community Grassroots Education: Social Learning at Standing Rock.” New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, no. 158, Summer 2018, pp. 47-56. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1002/ace.20278. Accessed 5 April 2020.