What is Critical in Critical Global Studies?

archive

What is Critical in Critical Global Studies?

The Critical Global Studies Institute (CGSI) has been based at Sogang University since 2016. Like its counterparts at institutions elsewhere, it was established in part to rescue the humanities and social sciences from the nation, offering a global outlook on humans, society, and the environment. How different is “Critical Global Studies” from other “global studies” approaches? What difference does the adjective “critical” make to global studies? What is critical in “Critical Global Studies”?

Critical Global Studies at Sogang University starts from the position that “globalization from below” is the alternative outlook to both “globalization from above” and anti-global nationalism. The perspective of globalization from below reflects the materiality of globalization, that it is already a part of our everyday life irrespective of our wishes and moral demands. Capital, technology, labor and culture are leaping over national borders, moving and circulating with speed. And problems related to the environment, human rights, and other critical concerns are emerging as issues demanding actions on a global scale, as shown by nuclear catastrophes in Chernobyl and Fukushima, global warming, yellow sandstorms of polluted particles in China, and other disasters.

The everyday life of ordinary people in the 21st century is rooted in a transnational matrix in which solutions to the problems above cannot be found within the nation-state framework. This reflection leads us to the idea that a return to the nation-state system and nationalism is an anachronistic way of thinking that ignores the realities of the current era of globalization. Critical global studies is derived from the consideration that the national paradigm, be it leftist or right-wing populist, cannot be an alternative to globalization from above imposed by global capital and the institutions that facilitate its power. The question is not the replacement of the global by the national, but the transformation of globalization from above into globalization from below.

Street art, India. Artist: C215 (Christian Guemy)

From the perspective of globalization from below, it is our position that “critical” global studies is a reasonable and even desirable political, cultural, academic and ethical orientation in dealing with global inequalities. Critical global studies rejects both the humanities of empire that erases differences and the diversity of human experience in the name of universality, and the humanities of the nation that essentializes ethnicities, nations and races in the name of particularity. Visions of the humanities must transcend artificial boundary formations regarding humans—such as nation, class, gender, race, culture, civilization, and religion—and ultimately be open to humankind. In this way “critical” global studies is a project of recovering the original vision of the humanities. Through its theoretical and practical outlook, CGSI has the ultimate mission of presenting the alternative to both the rising tide of nationalist anti-globalization and hegemonic globalization (“from above”), in the form of globalization from below.

Critical global studies rejects both the humanities of empire that erases differences and the diversity of human experience in the name of universality, and the humanities of the nation that essentializes ethnicities, nations and races in the name of particularity.

More specifically, CGSI’s vision for encountering the realities of 21st century life rooted in a transnational matrix can be summarized in four “trans-” keywords. They are elucidated in what follows:

Transnational connotes CGSI’s efforts to liberate our imagination from the fetish of the nation-state and cultivate cultural transfers crossing nation-state borders. The transnational approach tries to analyze not only interconnectedness in history, but also how this interconnectedness generates meaning in different contexts. Of course, it is not just about going beyond national boundaries. Multi-directional transfers and plural interconnectedness between different “historically constituted formations” or communicative spaces, including nation-states, cultures, regions, linguistic communities, generational groups, and gender boundaries, are scrutinized under the banner of “transnational.” Therefore, by “transnational” we intend not only an analytical label for the scope of study but also connections to the experiences of historical actors. Our target is methodological nationalism at the level of epistemology.

Methodological nationalism works not only in the realm of nation-states, but also in regional hegemony, requiring a critical transregional perspective as well. Various discourses of “European Union,” “East Asian community,” “Central Asia,” and other regionalisms transcend national borders. However, it is doubtful whether they are free from methodological nationalism in the domain of epistemology. Nation is inflated into a regional unit with the essentialist thinking intact. Thus regionalism contributes to justifying the hierarchical co-figuration of East and West and encouraging both the Orientalism and Occidentalism immanent to geo-positivism. The transregional approach would help us to deconstruct Orientalism and Occidentalism and cultivate the democratization of scholarship by de-essentializing the hierarchical division of East and West.

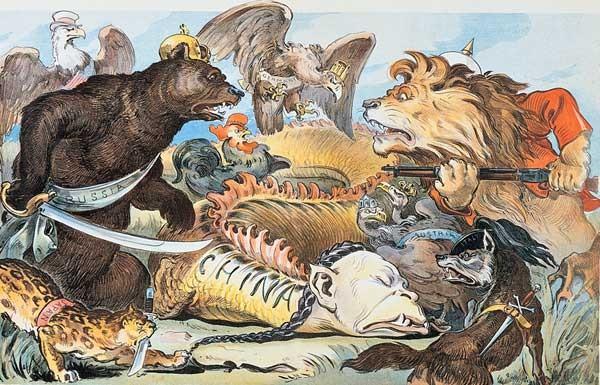

Western powers and Japan prepare to dismember China after the Boxer Rebellion

Through a transdisciplinary approach we try to move beyond interdisciplinary modes of inquiry. The archaeology of knowledge has proven that modern academic disciplines are the offspring of the nation-state and nationalism, which have been nourished through the strict divisions between academic disciplines. National history, national literature, national art and other nation-bound disciplines have kept their academic authenticity because the existential mode of the academic silo does not allow challenges from outside of the silo. Unfortunately, interdisciplinary inquiry proved not to be enough to defy the academic hegemony of national disciplines because it did not shatter the premise of disciplinary borders. The transdisciplinary approach tries to establish theoretical and practical groundwork for research with the explicit aim of crossing the borders of knowledge and ideas, and yet moving beyond interdisciplinary modes of inquiry.

Finally, CGSI is transinstitutional in its attempts to establish networks that surpass the boundaries of educational and research institutions to create and expand transcultural and transdisciplinary collaborations. CGSI established the Flying University of Transnational Humanities (FUTH) with an aim to resist, challenge, and overcome the rigid academic institutions imprisoned within the boundary of the nation-state. The academic goals of FUTH are to formulate a responsible and meaningful intellectual foundation for critical transnational studies by creating a worldwide on- and off-line network for collaboration among educators, researchers, and graduate students. Learning from the Polish experience of Uniwersytet Latający (“Flying University”), FUTH tries to accommodate the anti-institutional humanities as a counter-hegemony against the ideological hegemony of the modern nation-state, and develop epistemological conventions to support it.

The transregional approach would help us to deconstruct Orientalism and Occidentalism and cultivate the democratization of scholarship by de-essentializing the hierarchical division of East and West.

CGSI’s ultimate mission in incorporating these four “trans” concepts is to develop global ethics and epistemology, sharpen critical insight into multicultural and glocal lives, and promote the responsibilities and practices required of global citizens.

Women in The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. World War 2 era Japanese propaganda poster.

The focal point of CGSI’s research activities, based on this pedagogical foundation, is “transnational memory.” On the premise that globalization is a cognitive construction as much as a material reality, we assume that memory epitomizes the interplay of globalization between material reality and perceived reality. More specifically, transnational memory as a research project of CGSI pays attention to East Asia as a memory space. Despite the claims to irreversible progress that accompany almost every change of political regime, East Asia as an entangled memory space keeps reverting to the strictures of the past. Recognition of this leads us to the idea of “memory regime change” because memory of the past functions as a long-term cultural hegemony, unceasingly nullifying political progress. As seen in history, any strategy aimed at political change that leaves the memory regime intact has already proven itself a failure.

The project of transnational memory seeks to conduct, from a transitional perspective, critical investigations of multifarious layers and aspects of memory regimes such as official memory, managed by each nation-state, or vernacular memory as reproduced in the everyday lives of ordinary people. In particular, it pays attention to the problem that the “nationalization of people,” a process occurring in the realm of memory, widely regulates people’s ordinary, quotidian experiences. By scrutinizing the production, organization, distribution, and consumption pattern of collective memory, the project proposes that those concerned about memory regime changes in East Asia, whether they be historians, literary theoreticians, or film critics, should realize, albeit belatedly, that they all are “memory activists.” The four “trans-” orientations at CGSI may help these memory activists go beyond their conventional and professional confines and come together around the platform of transnational memory in East Asia.

Editor's note: This essay, part of a global-e series titled 'Global Studies in East Asia', was presented at the symposium “Global Studies in Japan and East Asia” held on November 12-13, 2016 to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the founding of the Graduate Program in Global Studies at Sophia University. David L. Wank, a sociologist and faculty member in the program, is guest editor of the series.