Exclusive Populism versus Inclusive Global Governance: A Response to Ahmet Davutoğlu

archive

Exclusive Populism versus Inclusive Global Governance: A Response to Ahmet Davutoğlu

In his global-e essay of March 30, 2017, Ahmet Davutoğlu provides a provocative and comprehensive assessment of current global trends and their impact on the future of world order. What sets Davutoğlu’s apart is an insistence that the ominous dangers posed by the current widespread crisis of government can only be overcome in an enduring manner if they are understood as arising from deeper structural causes and historic failures of political leadership at the global level. He calls particular attention to the unwillingness of the United States to provide enlightened leadership in establishing post-Cold War global governance that was both effective and legitimate.

In some respects, Davutoğlu is echoing Henry Kissinger’s lament a few years ago when he plaintively asked, “Are we facing a period in which forces beyond the restraints of any order determine the future?” This is coupled with Kissinger’s underlying worry: “Our age is insistently, at times almost desperately, in pursuit of a concept of world order.”1 Not surprisingly, Kissinger expresses nostalgic belief in the liberal world order that the U.S. took the lead in establishing after World War II. His idealizing of this order is articulated in a language no one in the global south could read without a good belly laugh. Supposedly this golden age was a reflection of “an American consensus—an inexorably expanding cooperative order of states observing common rules and norms, embracing liberal economic systems, foreswearing territorial conquest, respecting national sovereignty, and adopting participatory and democratic systems of governance.”2

While Kissinger looks back initially to the benevolent world order that emerged from World War II, he also is nostalgic for the 17th century Westphalian framework that gave legitimacy and effectiveness to a Eurocentric system that for centuries combined state sovereignty with colonial rule. The best he can offer to fix what is now broken is “a modernization of the Westphalian system informed by contemporary realities.” By the latter, he means primarily the rise of China and the dewesternization of the global setting, which calls for a restructuring in the form of accommodating non-Western values with respect to governance and cooperation, as well as mutually beneficial trade and security arrangements between authoritarian and liberal democratic forms of national governance.

What makes the comparison of Kissinger and Davutoğlu of interest is less their overlapping concerns than their sense of alternative goals. Kissinger, writing in a post-colonial period where hard and soft power have dispersed and especially moved East, considers the challenge one of reforming state-centric world order by a process of inter-civilizational accommodation and mutual respect, with a particular focus on the rise of China.

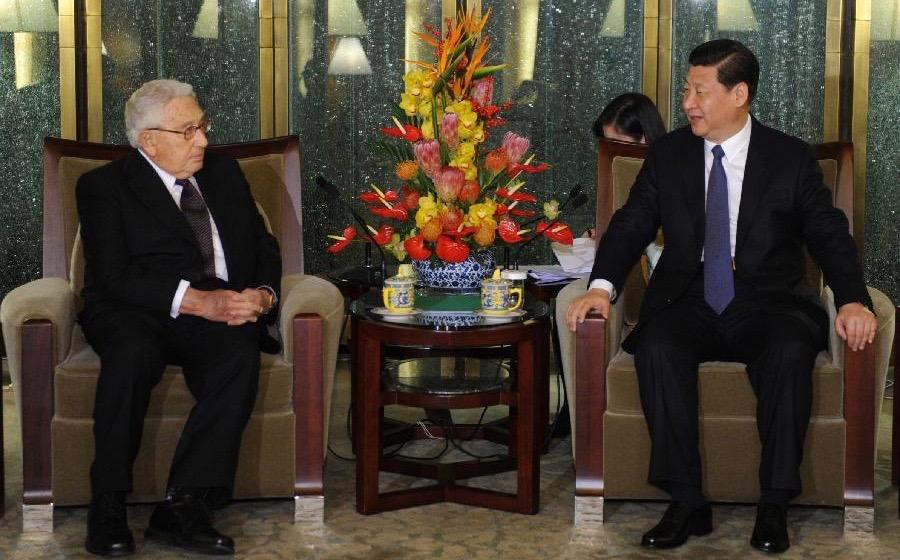

Henry Kissinger and Xi Jinping, 40th anniversary of release of the Shanghai Communique. Beijing, Jan. 16, 2012

In contrast, Davutoğlu sees the immediate crisis to be the result of inadequate global responses to a series of four “earthquakes” that have rocked the system in ways that greatly diminished its perceived legitimacy and functionality—that is, the capacity to offer solutions for the greatest challenges of the historical moment. This sequence of earthquakes (end of the Cold War, 9/11 attacks, financial breakdown starting in 2008, and Arab uprisings of 2011) occasioned responses that Davutoğlu derides as “short-termism and conjectural politics,” that is, ‘quick fixes,’ which failed to attend to the underlying causes, and thus did not address the problems in ways that would avoid recurrent crises in the future. It is this recurrent failure of global leadership that has given rise to the present malaise that Davutoğlu describes as “a rising tide of extremism,” a political spectrum with non-state groups like Daesh at one end and the populist surge producing such statist outcomes as Brexit and Trump at the other.

Davutoğlu finds three sets of disappointing tendencies that clarify his critique: the American abandonment of the liberal international order that it earlier established and managed; disappointing Western reactions to anti-authoritarian national upheavals as illustrated by the Arab Spring, in which the West withheld encouragement and, in some instances, acted contrary to its own declared democratic values; and more fundamentally, intransigence with respect to the need to reform existing international institutions in the economic and political spheres, particularly the UN, which is unable to act effectively until due account is taken of drastic changes in the global landscape over the course of the last 70 years.

The comparison between Davutoğlu and Kissinger is illuminating. Kissinger sees the main challenge as one of chaos that can be best overcome by establishing the U.S. and China as preeminent in a ‘live and let live’ geopolitical equilibrium presiding over a state-centric world order that works best if the power of the dominant states is balanced and their mutual interests served. Not a word about justice, human rights, the UN, climate change, and the abolition of nuclear weapons. In effect, Kissinger traverses the future as if a perilous journey across a normative desert, where success is measured by power games, and human rights and international law are treated as trivializing distractions from the challenges of statecraft. It is hardly a big surprise that Donald Trump should summon Kissinger to the White House amid the Comey crisis or that Kissinger would make himself available for an Oval Office photo op to shore up the challenged legitimacy of an imploding presidency. Trump, who knows less about foreign policy than my ten-year old granddaughter, described the visit as “an honor.”

It is this recurrent failure of global leadership that has given rise to the present malaise that Davutoğlu describes as “a rising tide of extremism,” a political spectrum with non-state groups like Daesh at one end and the populist surge producing such statist outcomes as Brexit and Trump at the other.

Davutoğlu’s perspective offers a more attractive response to an equally pessimistic diagnosis of the global situation. His fears and hopes center on an approach that might be described as ‘normative realism’ or ‘ethical pragmatism.’ In this fundamental respect Davutoğlu analyzes the challenges confronting humanity in light of the international structures that exist. He advocates the adaptation of these structures to current realities, but with a strong normative pull toward the fulfillment of their humane and democratizing potential. He counts on the United States to begin again playing up to its weight, especially as a normative leader and problem-solver. For this reason he strongly regrets the shrill Trump call of ‘America first’ as well as the sort of right-wing populism that has led to the rise of ultra-nationalist autocrats elsewhere on the planet.

Davutoğlu, a leading political figure in Turkey over the course of the last fifteen years, is an internationalist who seeks the incorporation of emerging economies and states through global reforms that achieve greater representativeness in international institutions and procedures. No personal achievement during his tenure as Foreign Minister brought Davutoğlu greater satisfaction than Turkey’s election to term membership in the UN Security Council, from his perspective the supreme recognition of status on the world stage. For Davutoğlu what matters most is such a certification of the legitimacy of state behavior as expressed by the collective approval of the community of nations represented at the UN. Kissinger is power-driven, while Davutoğlu is people-, values-, and community-oriented. In this regard, Davutoğlu’s worldview moves in the direction of normative pluralism, an acknowledgement of diverse civilizational constructs reinforced by crucial universalist dimensions, particularly as related to human dignity, justice, and human rights.

Ahmet Davutoğlu addresses the UN Security Council, 2012.

Although I share Davutoğlu’s diagnosis and overall prescriptions, I would point out several differences, perhaps only matters of emphasis. I think one of the distinctive features of the world order crisis is its insufficient capacity to address challenges of global scope, most notably climate change, but also the persistence and slow spread of nuclear weapons. The Westphalian approach to world order was premised on the interplay of geopolitical and state-centric forces, and was never until recent decades confronted by threats that imperiled the wellbeing, and possibly the survival, of the whole (species or world) as distinct from the part (state, empire, region, civilization). Rather than seeking to abolition nuclear weapons, the United States exerts control over a regime that aims to minimize their proliferation. This presupposes that the principal danger arises from countries that do not possess the weaponry rather from those that do. Such an arrangement is precarious, and creates a cleavage that splits human community at its core. This split occurs at the very time when greater confidence in human unity is urgently needed so that shared challenges can be effectively and fairly addressed.

Kissinger is power-driven, while Davutoğlu is people-, values-, and community-oriented. In this regard, Davutoğlu’s worldview moves in the direction of normative pluralism, an acknowledgement of diverse civilizational constructs reinforced by crucial universalist dimensions, particularly as related to human dignity, justice, and human rights.

In effect, I am contending that Davutoğlu’s prescriptive vision does not directly address a principal underlying cause of the current crisis—namely, the absence of institutional mechanisms and political will to promote human and global interests as well as national interests. Given present arrangements and attitudes, global challenges are not being adequately met by geopolitical leadership or through the aggregation of national interests. The Paris Climate Change Agreement of 2015 represents a heroic effort to stretch the limits of multilateralism, but it still falls menacingly short of what the scientific consensus informs us is necessary to avoid exceedingly harmful levels of global warming. Similarly, the sputtering response to the situation created by the North Korean crisis should serve as a wakeup call as to the precarious dysfunctionality of a geopolitical approach to nuclear weapons policy.

In the end, I share Davutoğlu’s call for the replacement of ‘international order’ (the Kissinger model) by ‘global governance’ (specified by Davutoğlu as “rule- and value-based, multilateral, consensual, fair, and inclusive form [of] global governance.” A possibly hopeful sign is that Chinese president Xi Jinping, talking to the 2017 World Economic Forum in Davos, endorsed a similar worldview.

1. Henry Kissinger, World Order. New York: Penguin, 2014, p. 2

2. ibid., p. 1