A New Axial Age? Opening and Disarray

archive

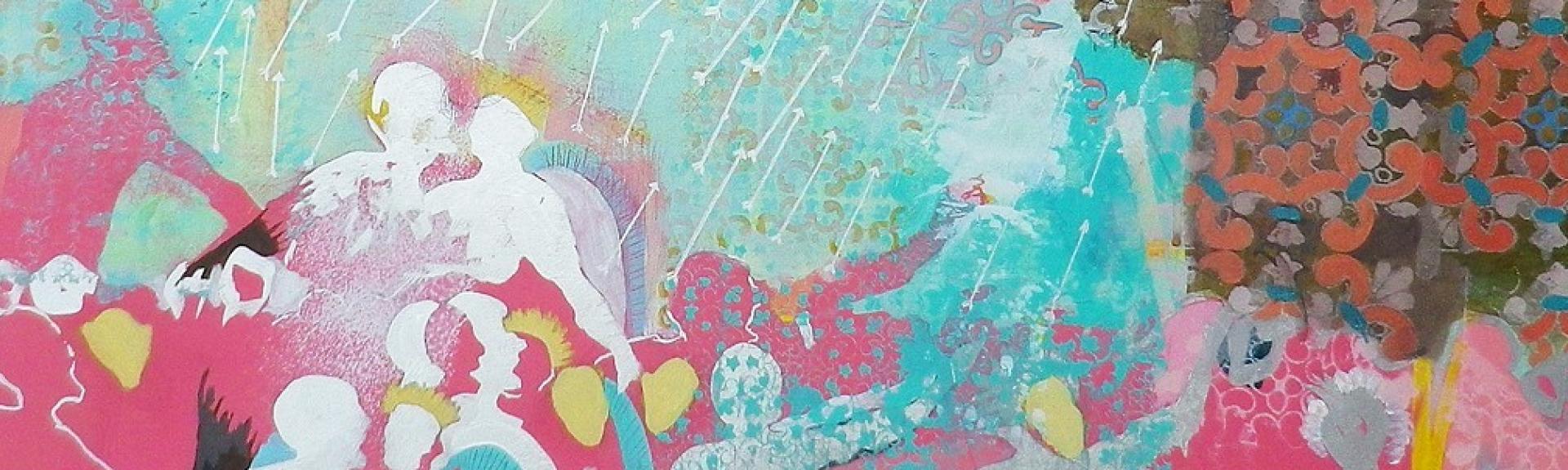

image (c) 2017 Crystal Latimer -- permission by artist.

A New Axial Age? Opening and Disarray

Are we experiencing an axial moment? The “axial age”1 has been used by scholars to define the long epoch marking the advent of the three monotheistic religions. As a retrospective concept, it seems unfit for thinking about our present, but the Scriptures and actions attributed to the leaders of those religious movements indicate an awareness of the momentous changes afoot during this era. Similarly, could we think of the current worldwide anguish as generated by the perception of some radical novelty that resists our effort to identify it? I want to consider the possibility that we may be going through something like an “opening,” somehow connected to public imagination on a broad scale, and highlight several aspects of it.

First, everyone and everything seems to be on the move and yet we are stuck. Seen from where I come from, North Africa, and many countries south of the Sahara, a sizable proportion of the youth really want to head north. Direction Europe: the wealthiest place on the planet, one that offers the possibility of better living and freedoms not available at “home.” Yet, so many are stuck in Northern Africa, to give just one example.2

Think of parallels in the Americas, the Levant and the Syrian killing fields, or Australia and elsewhere. We have innumerable accounts from refugee camps of the violence, genocides, ethnic cleansings, droughts, and famines that have put people in motion and yet trapped them in camps where their sense of being stuck generally goes unnoticed. Another reality not attended to is that the numerous transit states into which they pass are stuck with them as well.

Second, the ones who do not move resent the ones who succeed in moving back and forth amid the dejection of those left behind, and these resent even more the migratory ease of the global wealthy from North and South. The most important consequence is that states and international organizations still retain power on the frontiers between territories, but they are unable to stop the movement.

Third, change of place is now possible in the virtual world of the internet. Yet, being largely phantasmagoric, it fails to fulfill stringent desires. So, one may experience a full virtual life in Paris or New York but spend one’s ‘real’ life in Z’hiliga in Morocco, or Agadez in Niger. Worse, one would interact online with those who physically move about as they please.

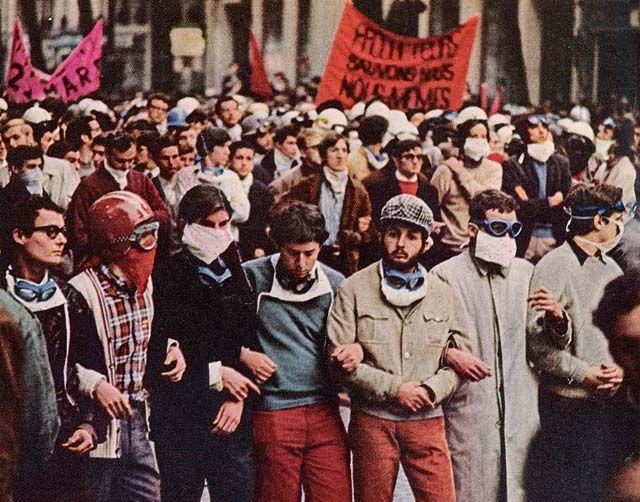

The changes we have been witnessing in the West since the late sixties may be pointing to an alteration of consciousness which correlates with an axial moment. May 1968 in France and its aftermath, the movement against the war in Vietnam, and all things New Age in the USA signaled the advent of new modes of change: revolution was not the transformation of a mode of production and the overthrow of the bourgeois classes and powers. It took a novel form: change happened through the erosion of the old bourgeois order.

Family, marriage, sex, gender, work, leisure, pleasure, politics, art, war, security, value, capital, inequality, equality… all those familiar figures were still alive, but none worked quite in the same ways as before. The welfare state muddled class issues. Consumption, and consumption of the “sign,” became paramount (branding being king).

Historicism ceded its place of honor to an archeology that ceaselessly turned around itself, unearthing geological strata of strange forms and chimera. In the meantime, poets of “advanced” capitalism made the pronouncement of the “end” of History.

What has in fact gained ground is an irresistible activity of grand collage production, everywhere generalized by new digital media with often baffling creativity. Collages of styles and times enlarged the market to technologies Marx could never have dreamt of. Thus, about anything could now turn up from any civilization past, contemporary, or virtually future, and at any moment, in this cosmic, sometimes comic, commodity-generating metempsychosis.

Image (c) 2017 Crystal Latimer -- permission by artist.

This sort of metempsychosis, I suggest, indexes an opening. It discloses the work of agentive forces we are unable to identify properly. It would seem that this is a classic case of a frontier of knowledge. Yet, to say that is not enough, for in this new situation things and voices from different times and places cross paths, often speaking to each other in tongues. These uncanny encounters may well be part of a watershed moment. That is why I use “opening” here coupled with “disarray.”

I want to consider the possibility that we may be going through something like an “opening,” somehow connected to public imagination on a broad scale...

My second contention is that the enduring reality of territorial states running nations more or less in flux is a fact worldwide. But it is crucial to note that those nations are not on the same side of the equation. For example, the breaking and (re-)making of Sudan cannot be lumped analytically with a possible one in Great Britain (involving Ireland and Scotland). Nor can it be lumped with the construction of a transnational Europe. Sudan belongs with the postcolonial weak and poor; Britain with the powerful and wealthy. Sudan was colonized. Britain colonized it. India, Indonesia, or Iran are among the relatively powerful, but not the wealthy, the Gulf States are among the wealthy, not the powerful. China is powerful, but one of a kind. The nuances may extend and proliferate with Brazil, South Africa, and others.

Financial and media centers may still be entrenched in the West, but movement comes from many other centers. Thus another novelty: movement without clear direction doesn’t translate as loss of agency, but as the work of myriad agencies. If that is what is happening in between surviving nations, what is happening within them? Anthropologists have rightly insisted that people are now everywhere confronting each other with their differences. These are cultural differences in search of the power to survive.

So what is crucially new here? One answer lies in the unmediated encounters of cultural difference. But this needs a vital qualification. Proponents of “culture” assume that it is a source of orientation for people. They usually discount dis-orientations that may stem from it. Critics posit social embeddedness of “culture.” They usually assume a structure hidden from people. Both neglect the enigmatic figures that cultural categories, in current circumstances, may take shape as for both “native” and anthropologist alike. Neither proponents nor critics pay attention to collage and the sort of metempsychosis I consider as major phenomena of our times, unfolding on the most global scale as a source of “opening” that is inseparable from “disarray.” Because terms and figures are metempsychosed, the people confronting each other are in fact at a loss as to what their identities should ultimately be about.

Anthropologists have rightly insisted that people are now everywhere confronting each other with their differences. These are cultural differences in search of the power to survive.

The region to which I belong, the majority Arabic speaking one, has had to take the full shock of that opening, with utterly devastating consequences. For it is perhaps the most globalized one in recent memory, at the heart of Western diplomacy and war and the world economy as a whole through the energy market. It is a grand, ghastly field experiment with the lives of its inhabitants. One face of it is the new form of colonialism and apartheid imposed by Israel on the Palestinians. Another is the one conducted by some Arab regimes that employ systemic violence, torture, and glaring forms of discriminations and inequality. A most telling experiment is the form of violence currently going on in the “Caliphate’s” dominions, a reign of terror that follows in the wake of the American experiment with a “New Middle East.” The region is but one experimental field, if perhaps a most gruesome one.

Thus, our historical moment of “opening and disarray” is a global reality of confounding reversals in politics and identity. How are we to understand, say, the sudden passages from Catholic to jihadist? And what about from secular to radically pious, or the back and forth between radical and quietist Islam? Nothing here is specific to Islam or religion. But how it works depends on which side of the opening a person resides. In the West one is confronted with seemingly infinite lifestyle “choices” available in a fast moving market. Elsewhere, it may mean living with the burdensome reality of being physically stuck while virtually on the move, or geographically contained while living the life of a restless refugee.

Image (c) 2017 Crystal Latimer -- permission by artist.

Today confrontation often occurs in enigmatic collages of cultural and linguistic expression. Actions may be taken or policies executed without much translation or mediation. But on the ground accommodations may happen regardless. This is not to say that we could dispense with understanding. Rather, it is to say that we need more of it. Because of the current overwhelming collage of cultural practices, it is often hard to envision grounds for commensurability. Perhaps only some leaps of creativity, similar to ones which seem to have occurred in an “axial age,” may bring some new directions to our times of extreme volatility. Originating in, and responding to, the predicament of “opening and disarray,” they may bring together the very diverse crisscrossing lives which are not on the same side of the global.

It is our distinct responsibility to hold on to another meaning of “opening,” which is: “promise.”

1. Karl Jaspers, The Origin and Goal of History. Routledge Reprints, 2011.

2. Mhani Alaoui, in her recent dissertation at Princeton University, provides

are obsessed by the desire to leave.

Collages by artist Crystal Latimer are copyright and reproduced by