Reflections on the Hindu Theory of Tolerance

archive

Reflections on the Hindu Theory of Tolerance

In recent years Hindu activists have attacked Christian missionaries, churches and mosques, and made distasteful remarks about Islam and Christianity. For their apologists these are uncharacteristic aberrations provoked by minority intransigence. On the other hand, their critics see these events as predictable expressions of the spirit of intolerance that lies at the heart of Hindu thought and which has long been obscured by the Orientalist myth of Hindu tolerance.

In this paper I step back from the immediate context of this controversy and use it to reflect on the basis and limits of Hindu tolerance. In the first part I elucidate the philosophical grounds and logical structure of the Hindu theory of tolerance. In the second I examine their strengths and weaknesses and conclude that the Hindu claim to tolerance is only partially sustainable.

The Hindu theory of tolerance is grounded in and overdetermined by the following four beliefs. First… [b]eliefs are not important in themselves but only insofar as they affect one’s ability to lead the good life, and are to be assessed not in terms of their cognitive validity but their moral effects. Secondly…[t]he ethically acceptable life is one lived according to dharma or a set of moral duties. Third…[f]or Hindus, every individual is the ultimate architect of his life and must work out his salvation himself. Fourth… ultimate reality is infinite and cannot by definition be grasped in its totality by the finite human mind. Different religions represent different and inherently partial visions of the ultimate reality and contain both truth and error. In the [Hindu] view certain values are so central to human life that they set limits to what constitutes a religion or one worthy of respect.

The Hindu theory of tolerance approaches the question of tolerance from an angle very different to that of most of its European counterparts. In some parts of India, several Hindu communities have both Hindu and non-Hindu customs for different spheres of life, and see nothing wrong in describing themselves as Muslim Hindus or Christian Hindus. Hindus widely worship Sai Baba, who was a Muslim saint. India is one of the very few countries in which public debates between the leaders of different religions were for long a common practice, and in which great religious seekers such as Ramakrishna Paramhansa and others experimented with different religious practices without the slightest inhibition.

While the Hindu theory of tolerance has these and other strengths, it also has its weaknesses, which partly explain periods of intolerance and inter-religious violence in Hindu societies. The weaknesses arise from the twofold fact that the grounds on which it justifies tolerance are not all mutually consistent, and they are not as unproblematic and benign as the Hindus like to think.

In the [Hindu] view certain values are so central to human life that they set limits to what constitutes a religion or one worthy of respect.

The combination of an extensive freedom of religious belief and the demand for conformity to social norms creates a paradox. The Hindu is free to hold whatever beliefs he likes as long as he observes his caste duties. This raises the question whether he may adopt beliefs that involve rejecting the caste system altogether while remaining a Hindu. Even if the whole caste embraces egalitarian beliefs as has happened sometimes, this has a limited practical value because the higher castes against whom the equality is asserted, rarely concede the claim.

As for religious pluralism, it is not at all as benign and egalitarian as it appears. Although it tolerates a wide variety of sects and ways of life, it does not grant them equal status and dignity. Hindu pluralism is not only hierarchically structured but is also the basis of a new hierarchy. Hindus are convinced that no religion can exhaust the plenitude of the infinite and that all religions are inherently partial and limited. In their view Hinduism acknowledges and respects these fundamental truths and was indeed the first to discover them. Other religious ignore these truths. They claim perfection, condemn or take a demeaning view of other religions, and deny their adherents the freedom to borrow from them. For Hindus these religions are therefore inferior. Many Hindu thinkers use religious pluralism to grade all religions, placing themselves at the top and Christianity and Islam at the bottom. Other religions are therefore tolerated and even respected but never treated as equals.

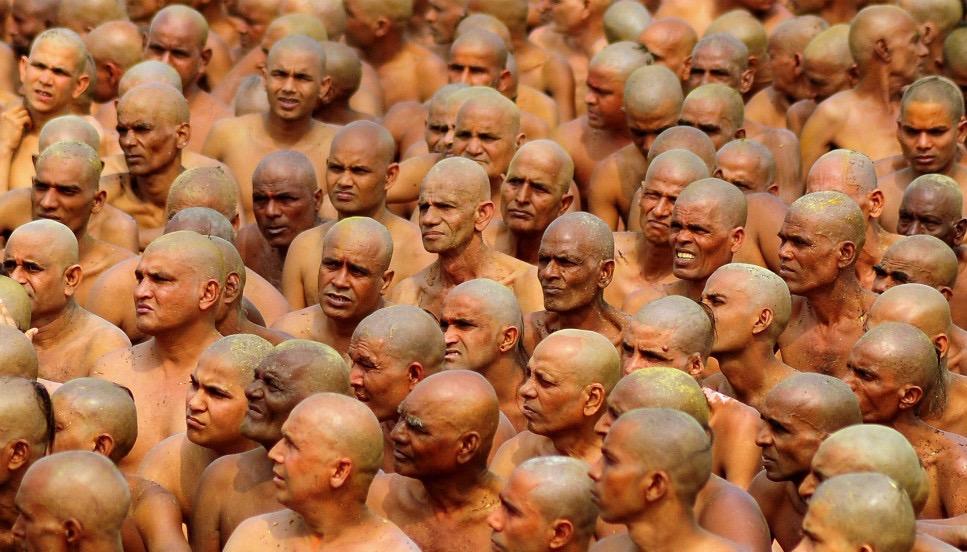

Naga Sadhu initiates, Maha Kumbh festival, Allahabad

Hindu pluralism is further handicapped by what Max Weber called absolute relativization. Every society is different and within each, castes, social groups, and individuals are unique as well. This form of pluralism makes it extremely difficult to take an overall view of society and restructure it on the basis of a shared vision of the good life. This may partly explain why utopian thought, a bold and imaginative reconstruction of society inspired by a will to change the world, is largely absent in Hindu thought. Relativized pluralism also freezes society. While it protects members against others’ interferences and ensures their negative freedom, it also severely restricts their choices, denies them the positive freedom to reject their way of life in favor of another, and discourages them from rebelling against the intolerable practices and institutions of their society.

The combination of an extensive freedom of religious belief and the demand for conformity to social norms creates a paradox. The Hindu is free to hold whatever beliefs he likes as long as he observes his caste duties.

Hindu pluralism is basically a form of peaceful coexistence with other religions in a spirit of relative indifference, each expected to remain confined to its boundary and never to challenge the other’s beliefs and practices. This might explain why few Hindu writers have produced either critical commentaries on or interpreted their own central doctrines from the standpoint of Islam, Christianity or even Sikhism. It may also explain why Hindus feel a deep sense of unease and even hostility towards religions that make universal claims and engage in proselytizing activities.

Another difficulty with Hindu pluralism lies in its reductionist account of religion. It asserts that all religions are basically concerned with the same thing, have the same goal, worship the same God, and are all so many different paths to the same destination. Their differences are acknowledged but believed to be unimportant, unrelated to the essence of religion, and attributed to ignorance or social and historical circumstances. Such a view of religion is simplistic and even false. Many religions have different concepts of God, and some even dispense with that concept altogether. The Buddhists are agnostics, and the Jains atheists. Brahman, the qualityless cosmic consciousness free of all human emotions including love and mercy, has little in common with the quasi-anthropomorphic conceptions of God common to the Hindu dualists and the three Semitic religions. And the latter three again differ greatly in their conceptualization of God.

Different religions, again, differ greatly in the way they relate to God and the universe, define human life and destiny, and imagine salvation. The dominant Hindu ideal of moksha has little in common with the popular Hindu and conventional Christian and Islamic views of salvation. Although all religions do share some moral principles in common, they define and prioritize them very differently. Given these and other deep differences, it makes little sense to say that all religions are so many different paths to an identical destination.

Bajrang Dal activists — youth wing of the Hindutva organization Viśva Hindū Pariṣada

Thanks to this reductionist tendency, Hindu thinkers, including the most eminent among them, have great difficulty appreciating the specificity and integrity of other religious traditions. Hindus tend to think of religion as a spiritual science, and of great religious leaders as spiritual explorers who through yogic training acquired the powers needed to discover the central truths of human existence. Since other religions see their prophets differently, even the most eminent and sensitive Hindu thinkers are unable to make much sense of them.

Religious pluralism has much to be said for it. It is a philosophically and morally superior view to religious monism or the claim that a particular religion represents the final word of God. It needs, however, to be based on non-assimilationist grounds. Religions are profoundly different and incommensurable. They are not all paths to the same destination, whatever that might mean, and are not all mutually translatable. It is precisely because they are different and incommensurable that the claim to absolute superiority by any one of them is logically incoherent.

Furthermore, since they are different, each can profit from a dialogue with others and appreciate both their uniqueness and commonalities. The dialogue not only uncovers such commonalities as may exist but also creatively develops them, and brings the religions closer in a spirit of mutual respect. Such a non-reductionist pluralism accords full and equal respect to all religions and avoids the arrogance of both religious monism and reductionist pluralism. It also has the further advantage of encouraging each religion to take a relaxed attitude to internal disagreement, fostering internal pluralism, and nurturing the spirit of intra- and inter-religious dialogue.

To create a tolerant India, we need to do two things. We obviously need to mobilize the Hindu resources for tolerance. But we also need to acknowledge and face up to its deep-seated tendencies towards intolerance, and subject them to a systematic egalitarian and pluralist critique. The Hindu religious tradition is too stubborn a political fact to be ignored and left to its orthodox and sometimes misguided guardians. And since it has resources for both good and evil, the only sensible course of action is neither to debunk nor to glorify it but to engage with it in a constructively critical spirit.

____________

Editor’s Note

This essay is adapted from an earlier version that appeared the popular Indian journal Seminar.

Bhikhu Parekh. Colonialism, Tradition and Reform. Delhi: Sage, 1989.

Pratap Bhanu Menta, 2001. “The Ethical Irrationality of the World: Weber