The Ebb and Flow of Latin America’s 'Pink Tide'

archive

The Ebb and Flow of Latin America’s 'Pink Tide'

Widespread democratic trends, competitive electoral politics, and greater access to elections characterize Latin American politics in the late 20th and 21st centuries. Many analysts argue that such tendencies index the ascendency of neo-liberal economic governance. Yet it was during the 2000s' that left-leaning governments came to power and a ‘pink tide’ took over in Latin America. This essay examines the reasons that led to the rise of the pink tide and questions the sustainability of its socialist oriented populist-economic measures. Will the pink tide be a recurring feature in Latin American Politics or does it signify a minor blip in a Fukuyamian evolution of Latin American political ideology?

The pink tide is a variant of socialism that saw socialist leaning/ left leaning leaders come to power in Latin America. They include Lula de Silva in Brazil and Michelle Bachelet in Chile, alongside the more revolutionary democratic socialists such as Evo Morales in Bolivia, the Kirchners in Argentina, Rafael Correa in Ecuador, and Hugo Chávez in Venezuela.

The leaders of the pink tide formulated their political platforms on populist themes. By advocating social welfare programs for the poor and promising socially just policies of redistribution (including structural reforms in the economy), they were able to garner the support of the disgruntled poorer, marginalized sections in society. Nationalization of foreign companies became a political slogan that gained considerable traction among the public. Neoliberal economic principles—built on the foundation of the Washington Consensus—were proclaimed to be the causa principalis behind Latin America’s financial burdens. Accordingly, populist policies attracted widespread attention and eventually, during elections, votes.

Anti-neoliberal protests in the 1990s following the U.S. push for the Washington Consensus and the defeat of the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) in 2005 are often cited as reasons for the rise of the pink tide movement. But a ‘butterfly effect’ such as this does not fully explain its ascendency. Stronger government intervention to rectify the economic malaise and an inherent desire to challenge the American hegemony through regional groupings such as the Community of Latin American and Caribbean states (CELAC) as well as the Bolivarian Alliance for the People of our America (ALBA) became the mainstay for the democratic socialists of the pink tide. Concerns about underdevelopment in contexts where economic neoliberalism was twinned with putatively democratic institutional structures, created tensions that intensified desires for radical change in many nations and communities. Rising income inequality in almost every Latin American country made it easy for the pink tide leaders to equate neoliberal economics with corruption and nepotism.

The pink tide therefore proposed alternatives that are often referred to under the rubric of neo-developmentalism,1 an economic model that is a critical of the overall reduction in the role of the state, which was a key feature of the Washington Consensus forged during the Reagan years. In essence, many of the principles such as privatization and deregulation advocated during the 1980s were turned upside down in the 1990s and 2000s by the pink tide movement.

The leaders of the pink tide formulated their political platforms on populist themes. By advocating social welfare programs for the poor and promising socially just policies of redistribution… they were able to garner the support of the disgruntled poorer, marginalized sections in society.

Based on the tenet of state activism, neo-developmentalism reflected a targeted developmental strategy. Production of high value added goods was identified as a key condition for economic growth. To realize this goal, neo-developmentalists advocated full employment and the diversion of labor to industries with high value addition per capita. However, state support to industries was strategic and not perpetual. In addition, the state was required to take immediate action to assure price, exchange rate, and financial stability. This targeted state intervention was sanctioned with the primary aim of supporting firms which were judged to be capable of competing internationally. Combined with populist state action to tackle rising income inequality and inflation, these measures were believed to create sustainable and long term economic growth in the domestic economy.

Given the overall dissatisfaction with the effects of the Washington Consensus in the region, it became relatively easy for pink tide leaders to portray the prevailing right wing governments as corrupt and unconcerned about public issues. Promising government activism and the amelioration of inequality, pink tide political movements rose to power and instituted sweeping social and economic changes.

Yet today we are witnessing the gradual retreat of the pink tide. Fiscal populism had been part of its policy backbone, but in Latin American economies—where there is still a high degree of dependence on export revenue from primary agricultural products and a few industrial goods—fiscal populist measures have proven unsustainable. For example, Chávez’s policies in Venezuela were underwritten by a flood of oil exports during a period when prices reached a highpoint of 100$ per barrel. This enabled him to launch social welfare schemes and offer subsidies that won him the support of a large majority of the Venezuelan public. This dependence on oil revenue resulted in the lack of political will to diversify Venezuela’s export base. When the price of oil dipped greatly in the 2014 to 2016 period, Maduro was unable to sustain the social welfare programs launched by his predecessor. Today, Venezuela's imports are down 50% from a year ago and the country faces critical shortages of essential imports, including medicines and food items. This has resulted in a daily flow of people across the border to neighboring Colombia to purchase essential items. With inflation soaring over 400%, the Central Bank recently stated that it has only just over $10 billion and close to $7.2 billion of debt. All in all, fiscal populist measures in countries that are dependent on export revenue generated from a few commodities are not a good recipe for sustainable economic growth.

The second major reason for the demise of the pink tide relates to corruption. While pink tide leaders claimed that neoliberal administrations engaged in rampant corruption, their socialist counterparts have been faced with similar allegations. A case in point is Brazil: the region’s largest non-nuclear power and the world’s fourth largest democracy. Brazil is in the midst of a political crisis that began in March 2014 with an investigation into allegations that Brazil's biggest construction firms overcharged the state oil company Petrobras for building contracts while paying bribes to former Brazilian President Lula De Silva, who is now being tried on charges that could result in a nine-and-a-half year prison term. Lula De Silva’s demise, which follows the ousting of his successor, Dilma Rousseff, demonstrates how rife the region is with corruption, whether governments are left or right leaning.

Yet today we are witnessing the gradual retreat of the pink tide. Fiscal populism had been part of its policy backbone, but in Latin American economies… fiscal populist measures have proven unsustainable.

Furthermore, despite promises of nationalization, major industries in Latin America (e.g., mining, media, and finance) are still in the hands of privileged elites that have enjoyed political and economic influence for decades if not centuries. Moreover, the problem of income inequality also has been left relatively unresolved by the pink tide leaders. For many of the Latin American leaders of the pink tide, pledges unfulfilled became particular sore points when it came to getting re-elected.

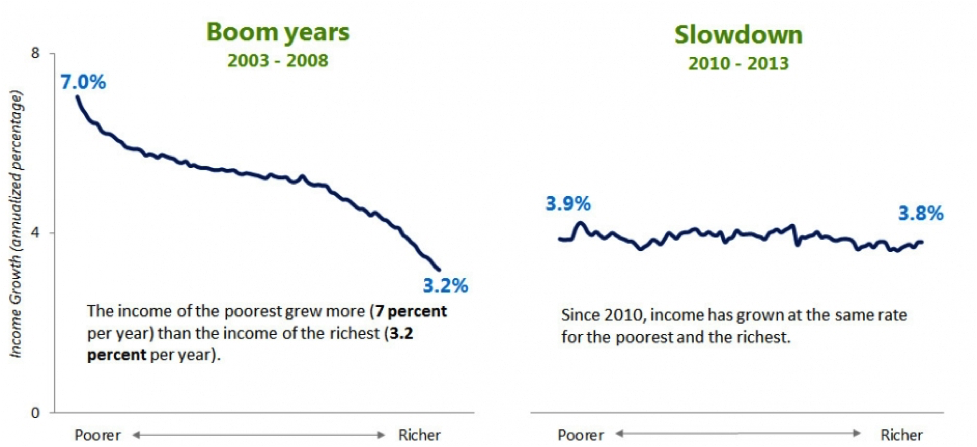

Graphic: Income growth in Latin America. Source: World Economic Forum

Finally, the promises of domestic industry promotion and rapid self-sufficiency in industrial and consumer goods became ‘mere rhetoric’ as China began to export many of its products to Latin America.2 Unable to compete against cheaper imports from China, many industries and firms in the region suffered from the competition and governments were unable to impose strong protectionist measures because of their ideological identification with China’s socialist policies. Moreover, China’s lending and investments to the region made Latin American economies dependent on Chinese goodwill. One frequently cited statistic in this regard is that China now lends more to Latin America and the Caribbean on an annual basis than the Inter-American Development Bank and the World Bank combined.3

Thus the pink tide reached its high water mark and has now begun to recede.4 Today, left leaning governments are being voted out of power (e.g., Argentina) experiencing political and economic turmoil (Venezuela), or facing corruption charges (Brazil). It remains to be seen whether this foretells a reversal towards neoliberalism or even a dialectic synthesis between the Washington Consensus and the pink tide’s populist version of neo-developmentalism but the changing political landscape suggests that the former may well be the case.

1. “Ten Theses on New Developmentalism.” São Paulo School of Economics of Getulio

http://www.networkideas.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Ten_Theses.pdf

2. Klinger, Julie. “China and Latin America. Problems of Possibilities.” Berkeley Review

3. Dollar, David. “China’s Investment in Latin America.” Geoeconomics and Global Issues

4. Sankey, Kyla. “What Happened to the Pink Tide?” Jacobin, July 27, 2016.