Land Injustices in Kenya’s Wildlife Conservancies

archive

wild antelope cross a road through the Olaroo Conservancy in Kenya's Maasai rangelands. Photo credit: the authors

Land Injustices in Kenya’s Wildlife Conservancies

A male giraffe struts across the road, and as he gradually recedes into the woods, his long neck and small head remain visible from a distance. The zebras and wildebeests have now stalled on their tracks, but they remain unfazed by the humans daily traversing the dirt road with motor vehicles and motorbikes. This is the enchanting vista at Olarro Conservancy, one of the many wildlife conservancies that have been established around Kenya’s Maasai Mara National Reserve (MMNR). While this scene suggests an environment where humans amicably co-exist with wildlife, closer scrutiny reveals layers of complexity.

The quest to simultaneously improve the quality of life for both humans and ‘other-than-human life’1 has proved to be an insurmountable challenge for environmental conservation around the world.2 With extensive changes in modes of land ownership, access, and use, Kenya’s Maasai rangelands are critical sites where human-human and human-wildlife relations are being negotiated in numerous ways. What were formerly community-owned lands are now being subdivided to create individually-owned plots. As the Maasai rangelands have been the hub of Kenya’s wildlife-based tourism, these shifting tenure regimes are engendering new approaches to wildlife conservation that have various impacts on indigenous Maasai peoples. This article discusses how the shifting tenure regimes entwine with novel approaches to wildlife conservation and wildlife-based tourism, and the implications for Maasai pastoral livelihoods.

Individualization of tenure and dispossession from within

The history of the Maasai features successive episodes of extensive land dispossession. During the British colonial period, indigenous Maasai were forced off their lands to create space for settler agriculture and wildlife conservation areas. Pastoralism, seen as an unproductive pursuit, justified the expropriation of Maasai land, forcing them to live in confined settlements that critically restricted their nomadic livelihoods.3

The Kenyan postcolonial state started to establish group ranches (GRs) in 1968, units of land owned communally under a shared title deed, saying that these would make the Maasai more economically productive. The leaders of the GRs were communally elected, offering a form of democratic devolution that would ensure representation of the Maasai pastoralists in matters of land and community development.4 With community land presumably secure in the hands of local leadership, it was thought that the Maasai had finally overcome the legacies of land dispossession.

However, due to a complex series of events, these land tenure initiatives have produced mixed results, largely because the GRs have been poorly managed, leaving many community members feeling insecure. As a result, demands for land subdivision and apportioning of individual land parcels ensued, enabling local male elites to conspire to grab valuable land while also illegally giving some of the land to non-GR members.5 Land subdivision therefore became a window for “land grabbing at every level with corrupt committees, Maasai elites, political leaders and outsiders arrogating to themselves the largest and best-placed Maasai lands.”6 What many had hoped to be a redemptive process for many Maasai people turned into land dispossession from within. Consequently, today the Maasai rangelands provide for adventurous sites of global tourism that obscure these past land injustices.

The rise of wildlife conservancies

As the individualization of tenure has proliferated, so have the approaches to and techniques of conservation so that most of Kenya’s wildlife is now residing in wildlife conservancies that are managed under the Kenyan Wildlife Act of 2013.7 The Kenya Wildlife Conservancies Association (KWCA)8 defines these locales as “land managed by an individual landowner, a body or corporate, [sic] group of owners or a community for purposes of wildlife conservation and other compatible land uses to better livelihoods.” In line with the KWCA’s definition, a wildlife conservancy can be privately owned, group owned (often with several landowners amalgamating their lands), or community owned (usually in cases where land is owned communally).

What many had hoped to be a redemptive process for many Maasai people turned into land dispossession from within. Consequently, today the Maasai rangelands provide for adventurous sites of global tourism that obscure these past land injustices.

In cases where land tenure is individualized it means that wildlife can only access the lands if landowners consent to this particular form of land use. Consequently, since most of the high potential land was appropriated by GR leaders and local elites,9 it means that wildlife revenues in these conservancies mainly accrue to the investors and a class of local leaders and elites, rather than to indigenous communities at large.

A neoliberal turn in Kenya’s wildlife conservancies?

The events in Kenya’s Maasailand unquestionably underline the centrality of land in sustaining humans and wildlife. What demands scrutiny, however, are the ways in which land is governed to create possibilities and in so doing, end up producing impossibilities for different groups of people. At the heart of wildlife conservation has been land privatization through individualization of tenure and the creation of wildlife conservancies where land has gained a double life: a real and a representative one.

In its double life, land becomes a commodity, albeit a fictitious one (following Polanyi10) that can be traded in realms that far exceed its geographical location. The commodification of land thus facilitates the creation of land markets, an achievement that Manji11 asserts has been pushed by global institutions to propel the expansion of neoliberal capitalism. The spread of neoliberal capitalism, Igoe and Brockington12 argue, is actualized through the restructuring of global processes to intensify the spread of ‘free markets.’ As Mansfield13 notes, “it is through privatization that neoliberalism becomes possible.”

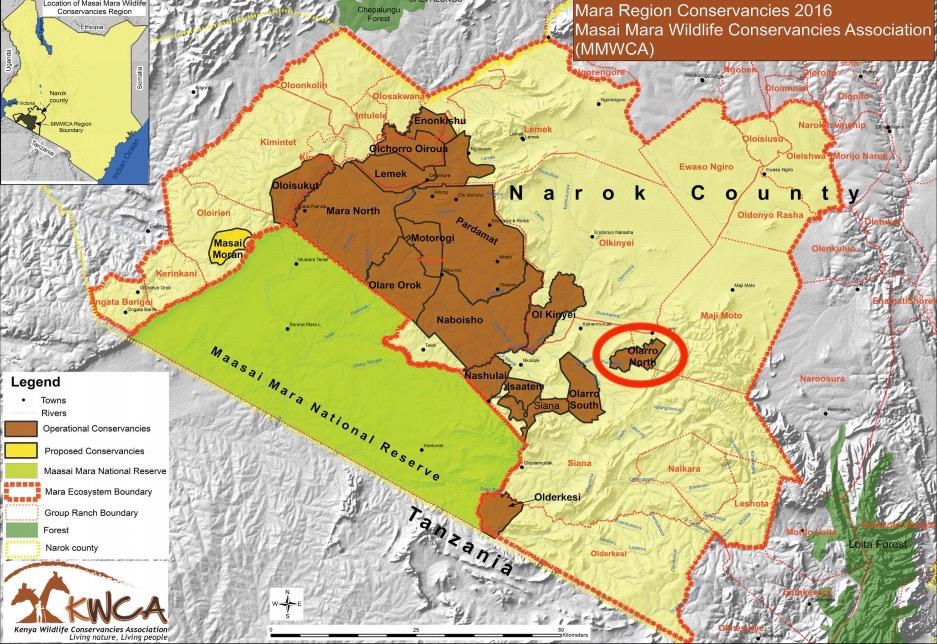

Conservancies under the Maasai Mara Wildlife Conservancies Association, including Olaroo North Conservancy.

These neoliberal dynamics in land and wildlife conservation come alive in the case of the Olarro North Conservancy, which is situated at the southwest tip of the former Maji Moto GR and the northeast of the former Siana GR. The Maji Moto GR, formerly governed under a collective private title deed, commenced land subdivision in 1999, eventually allocating 72 land parcels (out of a total of 2317 parcels) to the present-day Olarro North Conservancy. While the area may appear small relative to the entire GR, the planning and politics of the conservancy demonstrate the complexities that landowners are subjected to during a subdivision process that was strongly supported by foreign investors. Once land was individualized, subsequent negotiations essentially became private affairs, as did the decision-making processes and the benefits accruing from the conservancy. As the enclosure of power and control mechanisms of prime land in Maji Moto limited the opportunity for collective negotiation, the individualized parcels were re-collectivized, profits individualized, and the costs of wildlife conservation became externalized.

Maasi villager displays head of a bull recently killed by lions.

The externalization of conservation costs has been extensive even if subtle. On the one hand, the livestock herds of landowners who have leased land to the conservancy continue to graze on the lands of the rest of the community members, and because the conservancy remains unfenced, wildlife also freely access community lands outside the conservation area. This means that the burden of hosting both wildlife and beneficiaries’ livestock is borne by landowners who are not direct beneficiaries of the conservancy. On the other hand, the conservancy prohibits village grazing access, and heavy fines befall anyone found grazing within the conservancy. Thus, in various ways the conservancy has facilitated the commodification of land and wildlife, the enclosure of benefits, and land dispossession, and ultimately propelled neoliberal conservation in Maji Moto.

Conclusion

The process of land privatization and individualization of tenure in Kenya’s Maasai rangelands was anticipated to confer significant powers over land to individual landowners. However, individual tenure bears more complexities than often envisaged by local communities. These complexities are fast being manifested in areas such as the former Maji Moto GR where a wildlife conservancy has been established. In what appears to be a genuine social and environmental achievement is in reality a case of land dispossession from within which has the potential to trigger violent reactions. Wildlife conservancies established on such unresolved land injustices could thus be resting on thin ice. It will be important that the costs of conservation, mainly stemming from land dispossession from within during individualization of tenure, be addressed as a condition for realizing sustainable wildlife and biodiversity conservation that is of benefit for indigenous peoples.

1. ‘Other-than-human life’ refers to what has often been termed as ‘nature’, or the world around us.

2. Berkes, F. (2007). Community-based conservation in a globalized world. PNAS, 104(39), 15188-15193.

3. Hughes, L. (2006). Moving the Maasai: A colonial misadventure. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

4. Mwangi, E. (2007). Socioeconomic change and land use in Africa: The Transformation of Property Rights in Maaasailand. New York: Palgrave Macmillan; Riamit, S. K. (2013). Dissolving the Pastoral Commons, Enhancing Closures: Commercialization, Corruption and Colonial Continuities amongst Maasai Pastoralists of Southern Kenya. Unpublished Master’s dissertation, McGill University, Canada.

5. Ibid.

6. Bedelian, C. (2012). Conservation and ecotourism on privatised land in the Mara, Kenya: The case of conservancy land leases. Land Deal Politics Initiative Working Paper, No. 9, p.3.

7. Kenya Wildlife Conservancies Association. (2018). Retrieved from https://kwcakenya.com/conservancies/ on 15 March 2018.

8. Kenya Wildlife Conservancies Association. (2018). Retrieved from https://kwcakenya.com/conservancies/ on 15 March 2018.

9. Bedelian, C. (2012), op cit. Butt, B. (2016). Conservation, Neoliberalism, and Human Rights in Kenya’s Arid Lands. Humanity: an International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development, 7, 1, 91-110.

10. According to Karl Polanyi (2001:75-76), a commodity is something that is produced purposely to be sold on the market. As land is not produced by humans but occurs naturally, is therefore a ‘fictitious commodity.’ In Polanyi, K. (2001). The great transformation : The political and economic origins of our time (2nd Beacon paperback ed. ed.). Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

11. Manji, A. (2006). The Politics of Land Reform in Africa: From Communal Tenure to Free Markets. London: Zed.

12. Igoe, J., & D. Brockington (2007). Neoliberal Conservation: A Brief Introduction. Conservation and Society, 5, 4: 432-449.

13. Mansfield, B. (2009). Privatization : Property and the Remaking of Nature-Society Relations(Antipode book series). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, p. 6.