Framing a Global Approach to Peace

archive

Wakako Fukuda (right), founding member of Students Emergency Action for Liberal Democracy (SEALDs), during a protest outside the Diet in Tokyo, Aug. 2015. (Source: Reuters)

Framing a Global Approach to Peace

The modern international system is a product of the Peace of Westphalia, a treaty concluded between European empires at the end of the Thirty Years War in 1648. Based on the principles of noninterference and sovereign immunity of states, the international system was extended to the rest of the world, emerging from the early modern period as a result of Western territorial expansion, colonization, and imperialism. No less than an attempt to impose a vision of universalist or at least manageably contentious world order produced from Western political culture—possibly the modern West’s first truly universalist campaign—the “imperialism and colonialism that characterized international relations more than three centuries after 1648 were perfectly consistent with the tenets of the Peace of Westphalia.”1

But the existing world order and post-Cold War American hegemony are undergoing transformative pressures today that arise from both globalization and emerging regionalism. Moreover, today international law challenges the Westphalian principles of noninterference and sovereignty through international courts, tribunals, and norms such as humanitarian intervention and responsibility to protect. Another distinctive feature of the current transition is that non-governmental international institutions, civil society, and the private sector become increasingly influential on peace and its promulgation. These trends reflect the ideas of international relations theorists2 who have argued that the importance of the nation-states is diminishing in an era of postmodern globalization where the individual nation plays only a limited role in world affairs, particularly in areas concerned with international peace and security.

During the transition between old and new world orders, it is very important to build a framework paradigm for different approaches to peace. The transition to a post-industrial, multipolar, or multiplex world order, especially for the further development of global society, requires new ways of thinking and a better understanding of the theoretical and practical goals of peace from different perspectives, attentive to the conditions in which they can be realized and expanded. One of the pressing questions facing the international community at all times is how to achieve and maintain peace and security in the world. This essay sketches some of the work done to lay groundwork for one day integrating global approaches to peace.

To suggest a “global” approach is to denote more than just a theoretical extension of geographical boundaries or spaces. It can be a specific, distinct tool to analyze integration and structured global transformations, and foster a multiplicity of views on past and present issues of peace and security. No units or subjects of research in global affairs, such as development, conflict, or peacebuilding, can now be comprehended in isolation. The concept of peace is not an Eastern or Western invention; it is universal, its conceptual and practical origins stem from the early human civilizations, and thus it needs to be investigated in a global configuration.

But we should also not forget about various pitfalls when attempting to frame peace globally. Foremost is the difficulty of determining and agreeing on the meaning of “peace.” Different cultures, even different political orientations within the same culture, often tend to understand and explain peace differently: as the absence of war, communal harmony or inner peace, social integration, order or justice, public good, and so on.3 The next challenge is that there are no standardized global peace studies or global peace research programs. Research interests and priorities of scholars, policymakers, and institutions vary from country to country and from region to region.4 But in recent decades, the field of peace studies has changed considerably and remains dynamic, which in turn gives us hope that the gaps in global peace studies will be narrowed or removed in the near future.

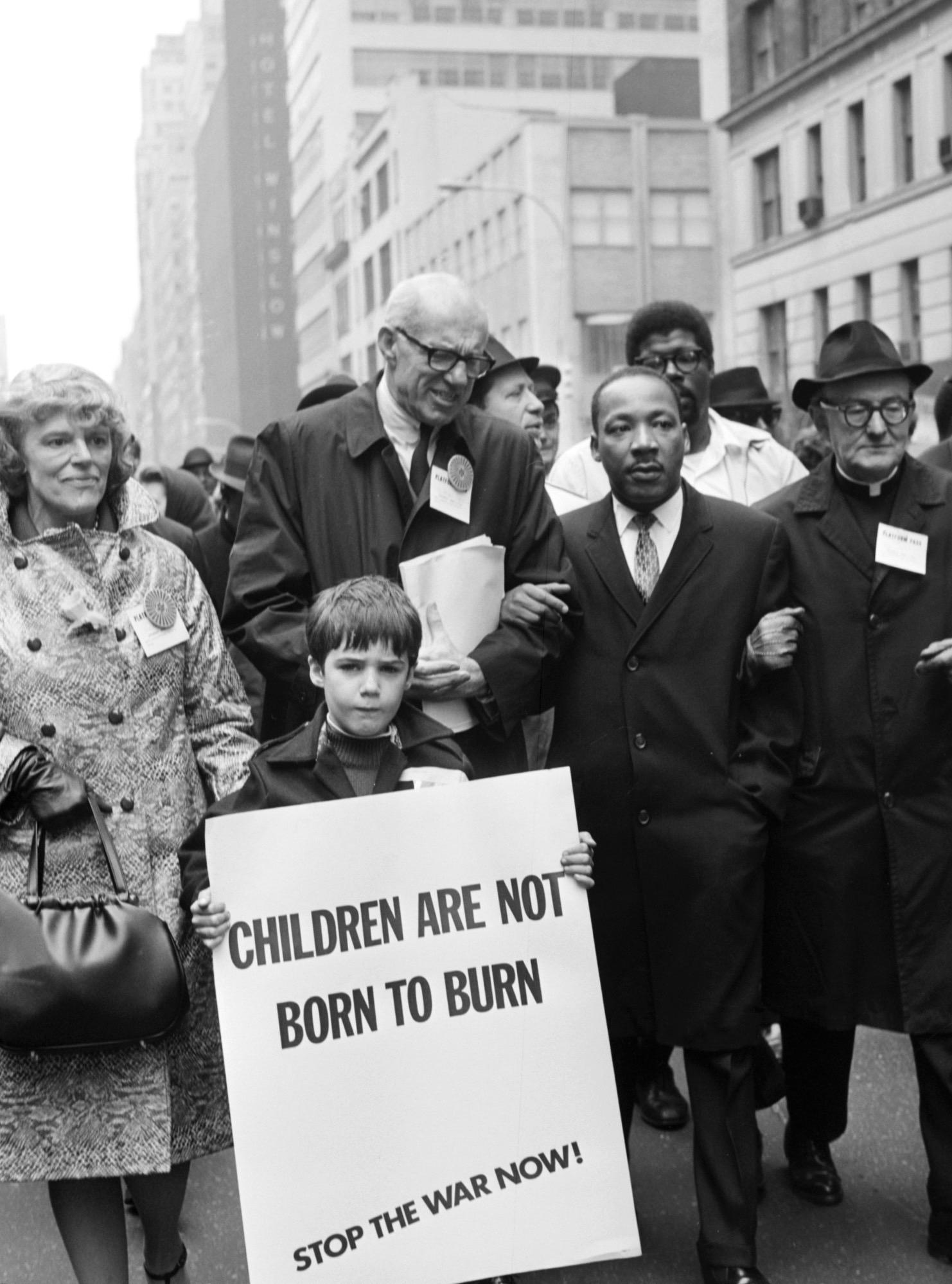

March 16, 1967 New York City protest against Vietnam War led by Dr. Benjamin Spock and Martin Luther King, Jr. Source: AFP/Getty

Beyond “Imperial” Models of Peace

In the twentieth century, Emery Reves [5] along with prominent activists of the World Federalist Movement, such as Mohandas Gandhi, Albert Einstein, Martin Luther King Jr., as well as our closer contemporaries, such as Richard Falk, David Held and others, insisted that only the authority of international law and international organizations could prevent future wars. Johan Galtung’s theory of “structural” or indirect violence introduced a new viewpoint different from predominant ideas of the time, emphasizing the discrepancy between the Global North and the Global South on the basis of historically persistent internal obstacles to development, stability, and peace in the latter. For Galtung, such structural violence could only be resolved through a deliberative, interactive, and dialogue-constructing approach built on Gandhi’s philosophy and practice of non-violence.6

He applied a sociological lens to the behavior of states in order to analyze their internal structure and relations with each other, illustrating structural violence in the dependence of the Global South on the Global North. He argued that a lasting, enduring peace is impossible until violence—both direct (with its extreme degree in war) and indirect or structural—is eliminated from international relations.

Most modern peace theories are grounded in the Western liberal tradition.7 Today there is growing skepticism about conflict resolution mechanisms and peacekeeping operations that are largely overseen by intergovernmental institutions influenced by Western, increasingly neoliberal policy mandates. While liberal theory is hardly exhausted, having put forward ideas like the rule of law, public goods, human rights, and civil society, its practical implementations are subject to constant criticism. With the transformation of the international unipolar system, approaches to peace, development, and peacebuilding based only on liberal (not to mention neoliberal) views of the world are no longer tenable. International relations, but also the disciplines of peace studies, will remain parochial until peace concepts, peace institutions, and peace practices are reframed globally with close attention to local conditions.

To suggest a “global” approach is to denote more than just a theoretical extension of geographical boundaries or spaces. It can be a specific, distinct tool to [...] foster a multiplicity of views on past and present issues of peace and security.

Besides the expanding interest in peace research, an unprecedented growth of peace movements occurred during the post-WWII period, which further influenced research and theory. This expanding engagement started as social agitation against nuclear weapons in reaction to the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Gradually a real surge in peace movements, both antiwar and nonviolent campaigns mainly against the wars in Southeast Asia and in support of decolonization, emerged in the 1960s. By 1990, the disintegration of the bipolar world system as a result of the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War further stimulated qualitative shifts in peace research, introducing new concepts such as peacebuilding. The United Nations was at the forefront of many of these changes.

In 1992, then UN Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali proposed a new policy concept for conflict prevention and conflict resolution in response to the rise of violent intrastate wars and interethnic conflicts, mainly in the Global South. In a document entitled the “Agenda for Peace,” Boutros-Ghali called upon UN member states to find a middle ground between “the needs of good internal governance and the requirements of an ever more interdependent world.”8 By launching four consecutive stages of international action—preventive diplomacy, peacemaking, peacekeeping, and peacebuilding—to reduce conflicts around the world, the “Agenda for Peace” formed a new peace framework, both strategic and practical, that dominated the field in the next decades. For the first time, the task of conflict prevention and conflict resolution was defined as local and national measures necessary to reduce the risk of (re)lapsing into conflict. Despite its contested meaning, the word “peacebuilding” has firmly entered the language of theory and policy research on peace.

Students in Mumbai, India participate in a peace rally to mark the 69th anniversary of US atomic bombing of Hiroshima, August 6, 2014. (Source: AP)

In the post-Cold War period, a new generation of international relations scholars began to emphasize the roles of local actors and local agency, culture, history, knowledge, and identity in postconflict peacebuilding.9 Eschewing top-down institutional (neoliberal) approaches, these scholars especially call for a rethinking of the role of cultural and historical contexts in contemporary peacebuilding practice, balancing the need for innovation with the need for historical continuity, emphasizing the dynamic potential and renewability of local cultural resources. While liberal peacebuilding privileges the “experiences, interests, and contemporary dilemmas” of the international interveners who conduct it, this approach overlooks the experiences, interests, and dilemmas of populations in conflict-affected states, as well as the value of their local knowledge.10

Approaching a Global Framework

One way to unify the many concepts, theories, and practices offered by scholars and practitioners to explain and implement “peace” is to employ the concept of levels of analysis. It should allow us to create a more inclusive research agenda that respects the diversity of epistemological and empirical traditions developed historically; to invite local knowledge into international peacemaking practice; and to advance further methodological pluralism to integrate intellectual orientations, extending them beyond narrow geographical and academic circulations. The diverse conceptual approaches refer to the knowledge or understanding of what peace is and how it develops in different schools of thought—cosmopolitanism, Gandhism, public goods, feminism, liberalism, human security, and so on. Then, domestic, regional, and systemic levels should be integrated. The increasing role of regions and regional institutions (EU, ASEAN, MERCOSUR, APSA, and post-Soviet Central Asian states, etc.) in peace and peacebuilding implies changes both at the macro-regional and the larger international levels.

As opposed to the more conventional approaches to maintaining peace generated at domestic, regional, and systemic levels—which can be coercive—alternative modalities emphasize less violent, “soft” means to conflict prevention, conflict resolution, and postconflict peacebuilding. Such approaches reexamine the concepts of peace institutions, engendered-sustainable peace, transitional justice, visual peace, the role of religion, and the contribution of international norms.11

Thus, the framework for global approaches to peace, based on conceptual, domestic, regional, systemic, and alternative levels and variations, creates a broader peace agenda at the crossroads of international relations and peace studies. This is one of the many ways to research, understand, and circulate ideas and the experiences of institutions and various processes related to peace and conflict resolution globally.

_______

This essay is adapted from Chapter 1 of The Palgrave Handbook of Global Approaches to Peace (Palgrave Macmillan 2019), co-edited by the author, who would like to express deep appreciation to all the authors for their important and timely contributions to the handbook.

1. B. Welling Hall, 2010. “Peace of Westphalia.” In N. J. Young (Ed.). The Oxford International Encyclopedia of Peace. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved from: http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195334685.001.0001....

2. Amitav Acharya, 2014. The End of American World Order. Cambridge: Polity Press; John J. Mearsheimer, 2014. The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (updated edition). New York: W.W. Norton & Company; Benjamin Miller, 2007. States, Nations, and the Great Powers: The Sources of Regional War and Peace. New York: Cambridge University Press; Thomas Weiss, 2011. Thinking About Global Governance: Why People and Ideas Matter? Abingdon, UK: Routledge, and others.

3. For example, see Takeshi Ishida, 1969. “Beyond Traditional Concepts of Peace in Different Cultures.” Journal of Peace Research 6(2), 133-145; Johan Galtung, 1967. Theories of Peace: A Synthetic Approach to Peace Thinking. Oslo: International Peace Research Institute; and Johan Galtung, 1981. “Social Cosmology and the Concept of Peace.” Journal of Peace Research 18(2), 183-199.

4. Peter Wallensteen points out that peace research in Africa largely focuses on natural resources, poverty, and neocolonialism; in Latin America, issues of militarism, social inequality, and unbalanced international relations receive greater attention; in Asian countries, such as India and Japan, the Gandhian nonviolent legacy and anti-nuclear peace campaigns caused by the tragic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are still predominant. See Peter Wallensteen, 2011. “The Growing Peace Research Agenda.” Occasional Paper 21: OP 4, 1-28. Joan B. Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies. University of Notre Dame, South Bend, Indiana, USA.

5. Emery Reves, 1945. The Anatomy of Peace. London: Penguin Books.

6. Johan Galtung, 1964. “A Structural Theory of Aggression.” Journal of Peace Research 1(2), 95-119; Johan Galtung, 1968. “A Structural Theory of Integration.” Journal of Peace Research 5(4), 375-395, and Johan Galtung, 2019. “Peace Institutions: Gandhism, Conflict Solution, Lifting the Bottom Up.” In A. Kulnazarova and V. Popovski (Eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Global Approaches to Peace. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 589-600.

7. For example, Weede’s and Gartzke’s ideas of “capitalist peace” emphasizes the integration of capital markets, which, in turn, develops cooperation rather than aggression between participant states. A similar viewpoint was proposed for the “democratic peace,” which postulates that “democracies do not fight with each other” because of their shared political institutions and normative values (E. Weede, 1996. Economic Development, Social Order, and World Politics. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner; E. Weede, 2005. Balance of Power, Globalization and the Capitalist Peace. Postdam, Germany: Liberal Verlag; and E. Gartzke, 2007. “The Capitalist Peace.” American Journal of Political Science 51(1), 166-191). The main opponents of the capitalist peace theory have always been socialists who believed that capitalism is unstable system because it creates levels of wealth and income inequality, eventually leading to social injustices. Socialists pay greater attention to intrastate conflict and primarily focus on the relationship between class and class conflict in capitalistic societies (H. Richards, 2010. “Socialist Approaches to War and Peace.” In N. J. Young (Ed.). The Oxford International Encyclopedia of Peace. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved from: http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195334685.001.0001....

8. Boutros Boutros-Ghali, 1992. An Agenda for Peace: Preventive Diplomacy, Peacemaking, and Peacekeeping: Report of the UN Secretary-General A/47/277—S/24111/2 July. New York: United Nations Archives, and Boutros Boutros-Ghali, 1994. Building Peace and Development: Report on the Work of the Organization from the Forty-Eighth to the Forty-Ninth Session of the General Assembly. New York: United Nations.

9. One of the first monographs on this subject that is worth mentioning is John Paul Lederach’s Preparing for Peace: Conflict Transformation Across Cultures, published in 1995 (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, p. 10), in which he argued that, “Understanding conflict and preparing appropriate models of handling it will necessarily be rooted in, and must respect and draw from, the cultural knowledge of a people.” Recently, more scholars such as Joanne Wallis and Oliver P. Richmond emphasize the importance of local knowledge in peacebuilding, and believe that, “Local knowledge is dynamic, contingent, flexible and hidden, and is influenced by habits, preferences, duties and virtues that stem from its social nature” (See Joanne Wallis and Oliver P. Richmond, 2017. “From Constructivist to Critical Engagements with Peacebuilding: Implications for Hybrid Peace.” Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal. Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23802014.2016.1309990). More on the subject of “local” peace, see Tobias Debiel, Thomas Held, and Ulrich Schneckener, 2016 (Eds.). Peacebuilding in Crisis: Rethinking Paradigms and Practices of Transnational Cooperation. Abingdon, UK: Routledge; Timothy Donais, 2009. “Empowerment or Imposition? Dilemmas of Local Ownership in Postconflict Peacebuilding Processes.” Peace and Change 34(1), 3-26; Roger Mac Ginty, 2016. “What Do We Mean When We Use the Term ‘Local’? Imaging and Framing the Local and the International in Relation to Peace and Order.” In T. Debiel, T. Held and U. Schneckener, 2016 (Eds.). Peacebuilding in Crisis: Rethinking Paradigms and Practices of Transnational Cooperation. Abingdon, UK: Routledge, pp. 193-209; Roger Mac Ginty and Oliver P. Richmond, 2013. “The Local Turn in Peace Building: A Critical Agenda for Peace.” Third World Quarterly 34(5), 763-783.

10. See, Joanne Wallis and Oliver P. Richmond, 2017. “From Constructivist to Critical Engagements with Peacebuilding: Implications for Hybrid Peace.” Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal, p. 8.

11. All of these approaches are discussed in The Palgrave Handbook of Global Approaches to Peace by prominent and emerging scholars in the field from all around the world. See, Aigul Kulnazarova and Vesselin Popovski, 2019. The Palgrave Handbook of Global Approaches to Peace. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Available for preview at: http://www.palgrave.com/9783319789040.