The Islamic State’s Passport Paradox

archive

The Islamic State’s Passport Paradox

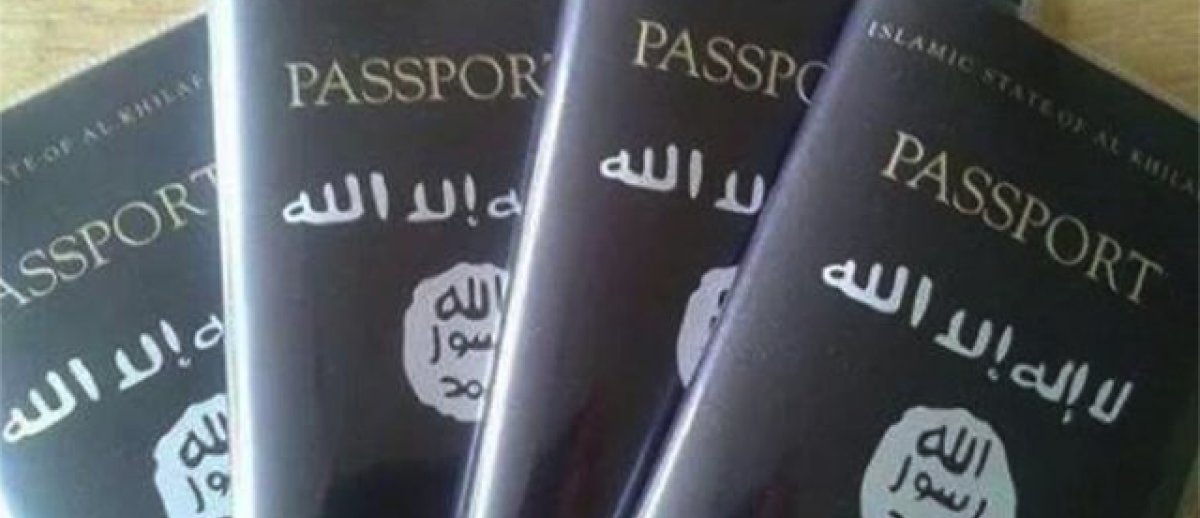

Shortly after ISIS declared itself “Islamic State” in 2014, images of purported passports circulated online. In August, 2014, Swedish terrorism analyst Magnus Ranstrop tweeted a photo of four passports strewn across a table (Figure 1). He found the image on an IS supporters’ website. They bore the group’s flag under the word “PASSPORT.” There were reasons to doubt the group sanctioned these, starting with the cheap, shiny laminated covers. The use of English and in particular an English transliteration of the Arabic word for Caliphate appeared odd. “Islamic State of Al Khilafah” is not an official name; it is redundant phrasing, basically saying Islamic State of the Islamic State. Most likely, these were a fan’s mock-ups made to express exuberance at the announcement of the Caliphate.

That same summer, a different image of a passport with a dark green bound leather cover also made the rounds on social media. Its ornate, emblazoned logo and full Arabic script made it appear legitimate (Figure 2). One report claimed that IS had issued it to 11,000 citizens who lived near the Iraq-Syria border. According to Al Arabiya, the group was using a captured Iraqi government “Identification and Passport Center” in Mosul to create the documents as an effort to boost morale and solidify its rule.

As a militant movement aspiring to statehood—one that was capturing and holding on to territory, and implementing a legal regime—IS would be expected to furnish its own passport. After all, it engaged in the formal administration of travel consistent with modern statehood practices, issuing safe-conduct passes and exit permits for exceptional circumstances. Furthermore, IS built bureaucratic structures to manage the populations it conquered. A passport would supplement these official efforts to regulate the movement and identities of individuals within and passing through its territories. Also, it would symbolically supplant the previous documents of foreign fighters who burnt their passports to show their full commitment to IS and reject their old citizenship. However, IS never systematically issued these or any passports to its entire population. Neither the group’s captured records nor media reports have made any mention of IS passports since 2014.

Besides being a juridical and functional artifact of sovereignty, a passport is a material canvas for power to demonstrate its legitimacy. This gives it an analyzable communicative pertinence. In the first instance, the decision to issue a passport is a declaration of having borders that demarcate national territory and is a geopolitical statement of inclusion among the larger community of nations. It matters for burgeoning international relations since a country’s official travel papers derive currency from other countries’ formal recognition of the authority vested in them. Perhaps, since IS saw its borders as fluid and did not recognize other states, it had no such purpose for national documents.

Figure 2. Purported real Islamic State passport.

Second, a state’s representation of itself is displayed on the passport’s cover and in its first pages via nomenclature, layout, and iconography. It inscribes a vision of its own identity and sources of legitimacy. This gives official documents an attractive symbolic power; governments-in-exile (Tibetan Green Book), para-state authorities (Palestinian Authority) or deeply unpopular regimes (North Korea) issue passports despite their having little utility for mobility in the world. It is probable that this is an under-whelming motive for IS, which may see a passport as a facsimile of nationalistic states.

Although IS had the impetus to release passports and the capacity to produce them, there may have been a deeper reason for not exercising that option: A passport foregrounds latent tensions in the group’s claims to sovereignty. Specifically, the first and most essential justification IS gave for its existence is a divine one, appealing to the “prophetic method” of declaring a Caliphate. While the religious sources, from the holy texts to the practices and sayings of the Prophet and his contemporaneous followers, offer a blueprint for a just Islamic authority, they give no direct guidance on the question of passports. A cosmic raison d’etat admittedly suggests their futility, but the group would have to construct a policy. Many within it would surely oppose the promotion of outward travel on theological grounds. In fatwa no. 48 (2014), the Al-Buhuth wa al-Eftaa’ Committee forbade leaving because it was “without gain for anyone who wants to travel to the land of disbelief.” According to such a view, passports serve no purpose because everything beyond its borders is antithetical to Islam.

Although IS had the impetus to release passports and the capacity to produce them, there may have been a deeper reason for not exercising that option: A passport foregrounds latent tensions in the group’s claims to sovereignty.

In practice, however, IS granted many exceptions. It promulgated a policy, for example, that “those living in Islamic State territory must obtain a permit from the Diwan al-Hisba in whatever wilaya (province) they live in if they wish to travel outside Islamic State territory for a limited period of time.” This would be a temporary substitute for an IS passport since travelers would use their old passports for the time being. If IS matured into a settled state, and citizens’ previous passports were invalidated, it would have to have a national passport to continue such permissions. Although having no clear theological backing, such a policy is consistent with the second rationale and source of inspiration for the state: a historical justification rooted in prior Islamic states. In its formation, IS claimed to resurrect the line of rightly governing Caliphs. While they deemed most historic Muslim rulers corrupt, even the Caliphs whom IS claimed to succeed gave out travel documents akin to passports; they facilitated the movement of travelers and others engaged in economic activity, diplomacy, and proselytizing. Some of the papyrus passports from early Caliphates—including the early Abbasids—have been preserved.

Since IS never concretized its territorial rule, and likely will lose it entirely by 2018, it is saved from having to decide about issuing a modern passport. The programmatic issuance of an official passport would have invited IS to clarify a coherent discourse around its sovereignty, reconciling itself as a divine, sanctified, religiously correct authority that is also historically rooted in an interrupted line of Caliphs. Islamic State’s officials may have come to see a national travel document as essential to the practical imperative of managing a state. This might alienate the religious purists within IS’s ranks, but it would find grounding in the desires of its fighters, residents and fans who celebrated mock-ups of a passport as a symbol of the state’s manifestation. As such, a passport, that small material artifact, could have forced the group’s first necessary compromise with the practices of sovereignty that still define sustainable, territorial political organization in the contemporary era.