Rallying: Imagination’s Political Process

archive

Rallying: Imagination’s Political Process

“We are dreamers and doers”

--Movement 4 Black Lives

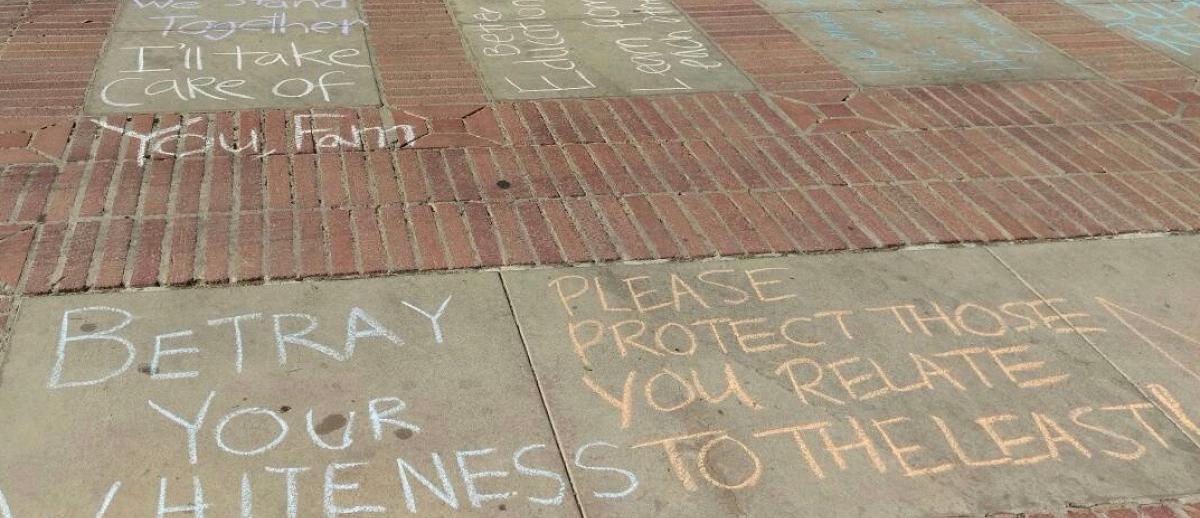

The association of imagination with make-believe and with disciplinary practices that characterize the humanities and fine arts has often been said to undermine its “street cred” and contributions to public policy. This essay argues the opposite. It puts into dialogue divergent strands of contemporary humanistic discourse on imagination to suggest why leaderless social movements such as Occupy, Black Lives Matter, and Dream Defenders are grounded in imaginative practices that are reinventing politics and why this re-orientation toward process over object is vital to the humanitarianism of political activity. People cannot be rallied to act if their spirits are incapable of rallying. The justice effected by such rallying depends on the extent to which people are committed to continually rethinking their identities, platforms, and aims.

Three of the most searching investigations of imagination come from the fields of British Romanticism, the Black Radical Tradition, and contemporary neuroscience. Despite their very different methods and objectives, writers in each field agree on features of imagination that specify its special approach to reality. (1) Imagination is a mode of perception that does not require immediate sensory input. What it perceives stems from its surrounding environment, but it is neither determined by nor invested in maintaining that environment as is. (2) Always in part constructing what it perceives, imagination is a form of mentation that also blurs distinctions between thinking and doing. Brain scans show that in action and imagination many of the same parts of the brain are activated, which is why visualizing can improve performance since both are products of the same motor program. (3) Its primary activity is connection-making, which involves also unmaking and remaking connections that have become entrained, hegemonic, deadening. Taken together, these features explain why imagination has long been considered a visionary faculty and the prime generator of creativity. Whether writers in these traditions emphasize neuronal or aesthetic mechanisms by which absent things are present in the mind/brain or are made present to consciousness, they contend that imagination broadens sense-based approaches to interpreting reality and works to extend thought and thoughtfulness beyond the empirical and the here and now.

Imagination’s circumvention of the common-sensical and reliance on unconscious processes are central to its creativity and to bringing the new into existence. This is why imagination has been deemed a revolutionary faculty and the engine of social reform. P. B. Shelley famously defends poetry—which for him encompasses all of the arts and humanities—by asserting that poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world. They are legislators because imaginative persons reshape public sentiment as a first step to producing more egalitarian laws and social policies; they are unacknowledged because policy-making is the putative domain of the social sciences and because imaginative activity is complex and indirect.

Romantic-era elevations of imagination as a moral as well as aesthetic faculty have rightly been censured for their possessive investment in whiteness and theoretical undergirding of a liberal subject whose alleged sympathy is tautologically self-involved. Does the fact that this has occurred—and that forms of white and state power continue to occur—invalidate imagination’s visionary potential? And should it discredit hope, as Afro-pessimists, no-future queer theorists, and Americanists asserting the cruelty of optimism contend? Probing this question is why I began by outlining convergences among such an unlikely ensemble of theorist-activists. To my mind, perceiving their congruence illustrates not only the function of metaphor in forging what Shelley terms “before unapprehended connections” but also the reasons why artists constantly must remake a culture’s figures of speaking so that they at once bespeak and focalize marginalized perspectives. This commitment to re-figuring thought is crucial to destabilizing racial regimes. As Cedric Robinson argues, because racial regimes are forgeries of memory and meaning rather than naturalized entities, the dominating connections that they have forged are vulnerable to protest. The trouble is that perceived vulnerability provokes primitive defenses, especially in those whose power is established and thereby unjustly maintained. Direct attacks are risky and thus require training in indirection by those whose claims have been redirected continually.

Imagination’s circumvention of the common-sensical and reliance on unconscious processes are central to its creativity and to bringing the new into existence. This is why imagination has been deemed a revolutionary faculty and the engine of social reform.

To the hegemonic workings of Romantic-era imaginations, then, the Black Radical tradition offers some basic correctives. The subject-object binary that founds Western conceptions of selfhood and democracy is grounded in slavery, treats others as things, and profits off of their subordination. To the degree that past or current imaginations isolate self from other, foster zero-sum mentalities, and affirm the sovereignty and immateriality of mind, they are ignorant about the brain and are using old power tools to renovate and secure master’s houses. By contrast, art in the Black Radical tradition is interested in collective and non-urbane renewals that prioritize process over objects. Black radical imagination is improvisational, at play in ensembles rather than in separate and separated individuals. Moreover, the freedom dreams that Black radicals conjure re-evoke massive resistances by no-things whose palpability in the present is the motor of whatever inspiration ensues. To say that histories of Black struggle are inseparable from histories of Black music sounds romanticized only if one hears struggle as dissonant or disconcerting and those qualities as unmusical. Here, the imaging of neuroscience is useful in registering that memory and imagination are part of the same network and that, when confronted with obstacles, neurons are resourceful at discovering new pathways. What “is,” that is, cannot be entirely separated from “was” or “ought,” but this does not make them an identity.

I catch something of this background in the call and responsiveness of Angela Davis’s “Power to the Imagination,” when she both delivered a lecture and took it to the streets as part of Occupy Philly in late October 2011. The transfer from “people” to “imagination,” with its implied shift of power from rights to rites and writing, is in keeping with an aesthetics of fugitivity and conceptualization of freedom as marronage. One can, and should, hear records of defeat in this transposition: minimal discernible shifts of power; palpable shiftiness in the terms of order; dead bodies of color left in the streets that “the 99%” ostensibly occupy; countless projects to wall people in and out. But articulating why this occasions yet should not sanction defeatism marks another convergence among my before-unconnected ensemble.

To the hegemonic workings of Romantic-era imaginations, then, the Black Radical tradition offers some basic correctives. The subject-object binary that founds Western conceptions of selfhood and democracy is grounded in slavery, treats others as things, and profits off of their subordination.

The conclusion that “despair is criminal,” reached by British Romantic-era radicals William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft in novels that expressly delineate the impossible obstacles that disenfranchised subjects confront in getting their stories heard, is rephrased but echoed in Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s conviction that subjects who are characteristically criminalized know that something more is going on and know just where it is happening and always has been happening—in the wild sociality of the undercommons. In such a space, all are welcome so long as they reject recognition and its demanding uplifts. Their type of disengagement does not mean that undercommoners are, or wish to be or remain, invisible. Or that they are not preparing for a fight. They are. And how. It’s that their imaginations are geared toward creativity, not identity, and their arts co-involve culture and struggle.

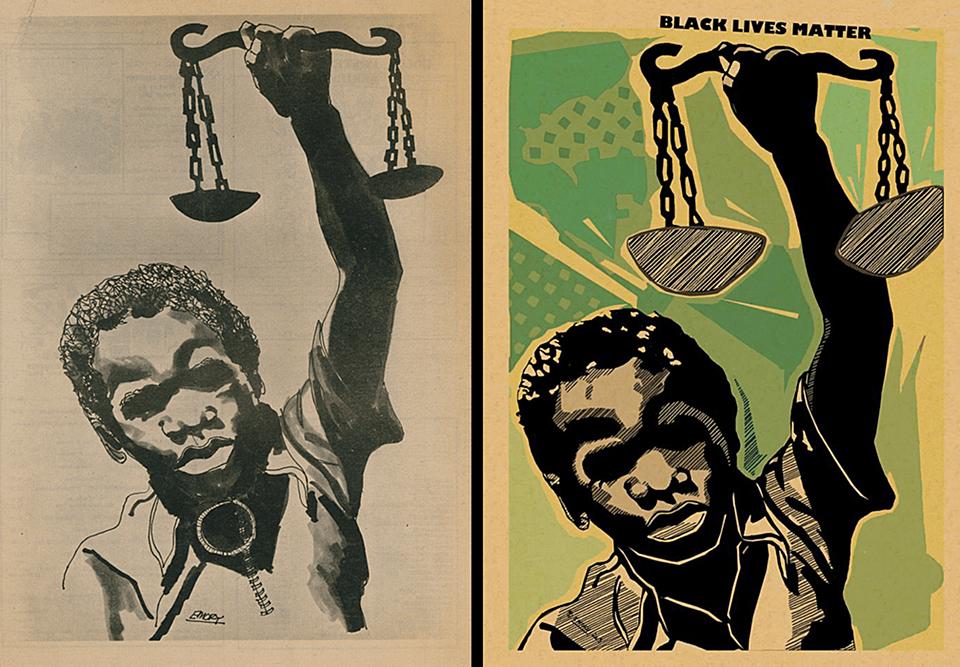

Original artwork by Emory Douglas. Source: Red Wedge Magazine

In other words, radical Romantic imaginations believe that despair is criminal because it hardens hearts permanently and thus forecloses possibility. While hardening is a reasonable response to being on the receiving end of racist projections and fire-power, Black radical improvisation keeps imaginations attuned to the sound of surprise. Staying open to surprise can be a crushing burden for subordinated peoples but it is also their lived reality, their history, and most moving legacy. For those who need or want to, acknowledging this reality foregrounds an aesthetic reason why Black Lives Matter, and why Blackness as radicals construe it remains avant garde. The bi-directionality between ought and is, whereby the “ought” of justice is situated in the “is” of double consciousness and its un-self-conscious forms of sociality, is what new social movements like Occupy Now or Black Lives Matter embody. Their reinvention of political life, as Davis puts it, is an artful practice that remains imaginative when the intersectionality it promotes extends to struggles, not simply identity categories. Also when its organizations reflect on the challenges offered by disorganization. This too is a basic lesson of the meaning-making mechanisms of the brain, wherein attentiveness requires ignoring vast arrays of input and brain efficiency dictates that connections become habitual and esteemed as high-cultural if there are not conscious and unconscious roadblocks designed to re-route them. The issue for imaginative activists is whether whatever gets assembled is then valued because of the exclusions its formation entails, or because it provides a temporary platform from which to conjure the before unapprehended. Cultivating desire for the latter is what the affective power of art strengthens by ensuring that persons do not face this void alone.

Andreasen, Nancy C. The Creative Brain: The Science of Genius. New York: Penguin, 2006.

Carlson, Julie A. “Romantic Poet Legislators: An End of Torture.” Speaking About Torture.

Eds. Julie A. Carlson and Elisabeth Weber. New York: Fordham, 2012.

Davis, Angela Y. Freedom is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations

of a Movement. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2016.

______ “Power to the Imagination,” (accessed 23 June 2017).

Doidge, Norman. The Brain that Changes Itself. New York: Penguin, 2007.

Godwin, William. Things as They Are; Or, The Adventures of Caleb Williams (1794).

https://archive.org/details/thingsastheyare00godwgoog

Harney, Stefano and Fred Moten. The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study,

Kelley, Robin. D. G. Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination. Boston: Beacon

Modell, Arnold H. Imagination and the Meaningful Brain. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003.

Moten, Fred. In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition. Minneapolis and

London: University of Minnesota Press, 2003.

Roberts, Neil. Freedom as Marronage. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Robinson, Cedric J. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. Chapel Hill

______ Forgeries of Memory and Meaning: Blacks and the Regimes of Race in American

Theater and Film Before World War II. Chapel Hill: The University of North

Carolina Press, 2007.

______ The Terms of Order: Political Leadership and the Myth of Leadership.

Albany: State University of New York Press, 1980.

Shelley, Percy Bysshe. A Defence of Poetry (1821).

Wollstonecraft, Mary. Maria; or The Wrongs of Woman (1798).

Zeki, Semir. Splendors and Miseries of the Brain: Love, Creativity, and the Quest for