Might There Be an After, After 9/11?

archive

Photo: Andrea Nieto, Getty Images

Might There Be an After, After 9/11?

In the years since September 11, 2001 pundits, politicians, and scholars of terrorism and international relations have routinely declared that 9/11 “changed everything.” As the years have passed these declarations also have implied that the change was inevitable. One important component of the explanation for the immutable nature of this belief is the failure to acknowledge that many of the decisions that were undertaken in the immediate aftermath of the attacks were not the only possible reactions. The “War on Terror,” the Patriot Act, the War in Afghanistan and later the War in Iraq were all assertive choices—not automatic or necessary options. With the end of the Obama administration and with the first year of Trump now behind us, it is reasonable to ask if there is any opportunity to think that there may be an after, after 9/11.

In answering the question it is useful to begin with the observation of E.V. Walter (1969) that the reactions (by the audience) to a terrorist event are far more important for understanding the consequences of a terrorist attack than the original action. Thus, how policy makers and publics react to terrorist events are far more important than the number of victims. And as the last sixteen years have sadly demonstrated, the choices set in motion in the immediate aftermath of the attacks were disastrous for the long run for both the United States and much of the international system.

The Bush administration set the frame and the justifications for it. Most consequential beyond the catastrophe of the violent behaviors was the constant assertion of the “existential threat” that al Qaeda and Islamic terrorism presented. The early acceptance by American public officials, elites, and the general public that terrorism was an existential threat was given support when both NATO and the United Nations Security Council (through resolutions 1368, 1373 and 1386) supported the US military attacks on, and occupation of, Afghanistan. The securitization that accompanied many national responses to the attacks and the fear of more attacks also made clear the persistence the central role of sovereignty claims within the global governance regime of the Westphalian interstate system. There have been many consequences of these reassertions of sovereignty and the primacy of security in the context of framing terrorism as an existential threat. These include challenges to what previously had been seen as strong norms concerning the rights of combatants, prisoners, and citizens. Over time they have not only affected conditions on the ground in nations at war but also migration, refugees, and the movement of people across borders as well as the responsibilities of states to them. These challenges have been witnessed not only in and by autocracies but also in and by the democracies whose long-term support for the human rights norms established by the United Nations has also waned. Perhaps most importantly, the framing of the threat has generated response frames, attitudes, and behaviors that many thought had disappeared with the end of the cold war.

The option that continued to be dismissed after 9/11 was the traditional law enforcement approach rather than the military one that was predominant from the 1960s until 2001. A suggestion to “Keep calm and carry on” did not have (and continues not to have) any political foundation and was unlikely to be judged as a politically winning approach in the post 9/11 world that had been created. Thus the War on Terror prevailed for the whole of the Bush presidency and into the administration of Barack Obama. Much has been written on why the war metaphor was a counterproductive rhetorical and tactical strategy for counterterrorism and so there was much hope when Obama, on his first day in office, issued a series of executive orders to distance the new administration from Mr. Bush’s strategy and demarcate a stated new approach to confronting terrorism—i.e., one based on law enforcement principles. The new president ordered the closure of the CIAs secret prisons, required the CIA to abide by the same interrogation standards as the military, revoked past presidential directives that authorized abusive treatment of prisoners, and recognized and reaffirmed U.S. adherence to the Geneva conventions. Further, over the next few weeks Mr. Obama reframed the discussion of counterterrorism away from the Bush Global War on Terrorism to the much less elegant and forceful sounding phrase of Overseas Contingency operations to signal the shift in military, legal, and intelligence approaches by his administration.

the choices set in motion in the immediate aftermath of the attacks were disastrous for the long run for both the United States and much of the international system.

But these changes, while they challenged some of the political narrative that had been established in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, did not challenge the main frame that “9/11 changed everything” and did not undo many of the other changes that were put in motion as a result of that frame. And as has been frequently commented upon from civil libertarians who were quite disappointed with the Obama justice department approach to much of the legal architecture and reasoning with respect to the Bush administration legacy, not enough truly changed in the implementation of counterterrorism policy (see Stohl, 2011:112).1

Perhaps even more importantly in terms of extending the 9/11 frame, President Obama and his national security team did not then, nor during his entire presidency, challenge the other foundational cornerstone of the War on Terror—the network metaphor. As a result, much of the strength of the War on Terror narrative continued as the core political narrative of the post 9/11 era.2

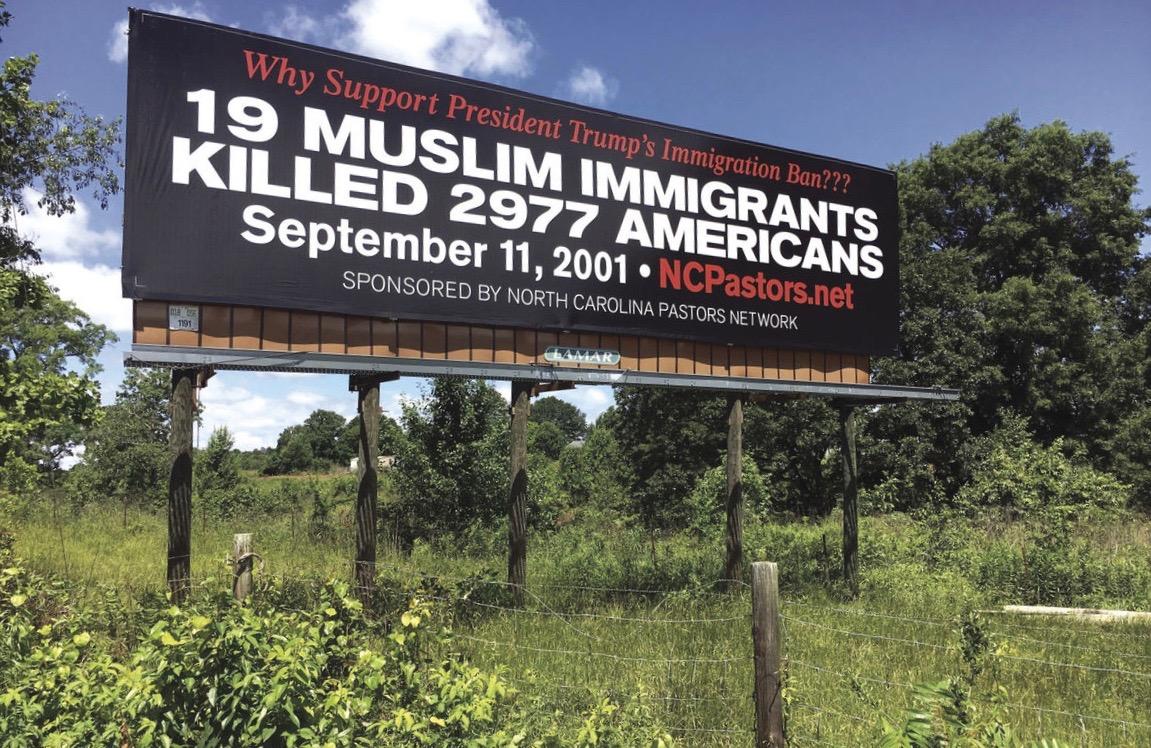

May 2017, along Interstate 40, Catawba County North Carolina. Image: WSOC-TV

Donald Trump’s victory in the 2016 presidential election made clear to political pundits and much of the American public that the anger of white voters was in large part generated by the transformation of the American and global economies, but these transformations also were coupled with the War on Terror which helped to fuel, once again, nativist “identity” politics with respect to immigrants, which have been expressed in successive waves since the mid-nineteenth century. The perceived economic threat that immigrants represent is exacerbated by fears of violence and terrorism, as during the anarchist scare of the late nineteenth century and the Red Scare after World War I, both of which were accompanied by attacks on immigrants and immigration policies.

A suggestion to “Keep calm and carry on” did not have (and continues not to have) any political foundation and was unlikely to be judged as a politically winning approach in the post 9/11 world that had been created.

While I have argued above that the Obama administration failed to alter the 9/11 narrative, Obama’s reflections on the threat of terrorism and the underlying approach to counterterrorism delivered on December 6, 2016 at least finally put the threat of terrorism into proper historical perspective. Still, absent his willingness to turn away from the network metaphor he still did not do enough to argue for an after, after 9/11 world. President Trump in his first year continued the narrative that the threat was existential and networked and, moreover, insisted that Obama’s policies made the US weaker and the threat of terrorism greater. However, he did so while continuing the Obama administration counterterrorism military activities while reducing civilian involvement and oversight, leaving much greater latitude to the military in terms of operational decisions. The most important difference in Trump’s approach was the tying together of the terrorist threat and immigration, with all its damaging consequences for DACA, the undocumented community, and immigration policy, as well as for refugees, asylum seekers, and respect for the narrative of the American dream.

While we can have no illusions that President Trump’s inclinations are to implement any helpful policies that will contribute to an after, after 9/11 world, on January 19, 2018, Secretary of Defense James Mattis presented the newly unveiled publicly available portion of the National Defense Strategy, which argues that “Inter-state strategic competition, not terrorism, is now the primary concern in U.S. national security.” This is not an endorsement of the new NDS as there are many potential negative consequences contained within it, but for the first time since 9/11 the threat of terrorism is not designated by the United States government as the dominant or existential threat to the United States. Whether this provides an opportunity to alter the post 9/11 narrative that has dominated the past seventeen years will only be known when we witness the rhetoric and response that follows the next attack. Still, for the first time since 9/11 perhaps there is a glimmer of hope for an after, after 9/11 world.

_________

This contribution is taken from “There’s only three things he mentions in a sentence – a noun, a verb, and 9/11.” Presented at the Orfalea Center for Global and International Studies workshop Is there an After After 9/11: Terrorism threats, challenges and responses, January 19-20, 2018

1. The U.S. still reserves the right to hold suspected terrorists indefinitely without charge, try them via military tribunal, keep them imprisoned even if they are acquitted, and kill them in foreign countries with which America is not formally at war (including Yemen, Somalia, and Pakistan). When Obama closed the secret CIA prisons known as “black sites,” he specifically allowed for temporary detention facilities where a suspect could be taken before being sent to a foreign or domestic prison, a practice known as “rendition”. (See Blakeley and Raphael https://www.therenditionproject.org.uk) And even where the Obama White House has made a show of how it has broken with the Bush administration, such as outlawing enhanced interrogation techniques, it did so through executive order, which can be reversed at any time by the sitting president and as we have seen by his successor.

2. See Stohl and Stohl 2007 for an examination of the use of network metaphor under President Bush and its consequences.

Bush, George W. 2001. “Address to Congress and the American People Following the Sept. 11, 2001 Attacks.” Retrieved January 2, 2018 from

http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=58057

Danner, Mark 2017. Spiral: Trapped in the Forever War. New York: Simon &Schuster.

Obama, Barak 2016. Remarks by the President on the Administration's Approach to Counterterrorism, MacDill Air Force Base Tampa, Florida, December 06, 2016.

Retrieved January 2, 2018 from

https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2016/12/06/remarks-president-administrations-approach-counterterrorism

Stohl, C. and Stohl, M. (2007). “Networks of Terror: Theoretical Assumptions and Pragmatic Consequences.” Communication Theory 47, 2:93-124

Stohl, M. 2011. “U.S Homeland Security, the Global War on Terror and Militarism,” in Kostas Gouliamos and Christos Kassimeris (eds.) The Marketing of War in the Age of Neo Militarism, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. Pp.107-123.

U .S. Department of Defense. (2018). Summary of the United States Defense Strategy:

https://www.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2018-National-Defense-Strategy-Summary.pdf

Walter, E.V. 1969. Terror and Resistance: a study of political violence, with case studies of some primitive African communities. Oxford: Oxford University Press.