Decoupling and the Politics of Legitimacy in Buenos Aires’ Bachilleratos Populares

archive

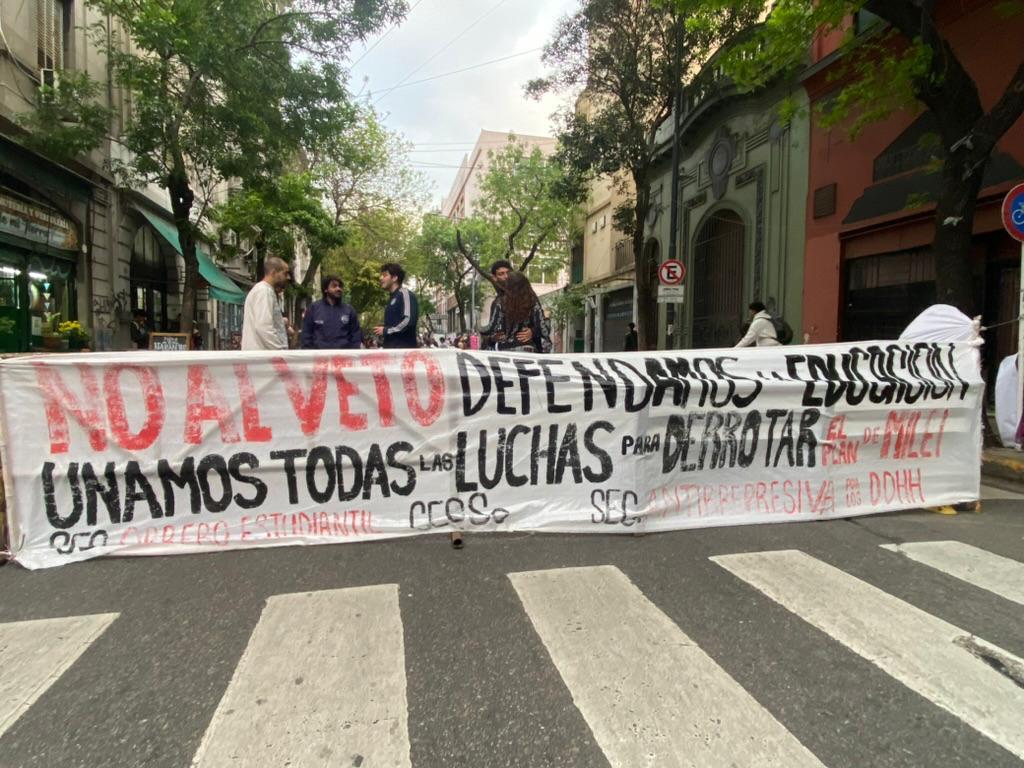

“No to the Veto”: University students protest Milei’s defunding of public higher education.

Decoupling and the Politics of Legitimacy in Buenos Aires’ Bachilleratos Populares

(All names in this article were changed for the privacy of interviewees)

Bachilleratos Populares (henceforth BPs) are autonomous, community-organized high schools for adults in Argentina. They form part of a Latin American tradition of educación popular, a liberatory educational praxis aimed at structural social transformation. For over a year, I conducted ethnographic research at two BPs in Buenos Aires, observing classrooms, teaching, and interviewing educators. I aimed to understand how these community-organized high schools navigate the state’s demands for formal accreditation while pursuing a socially transformative mission.

My research was motivated by various case studies that indicate a tendency for democratic, community-organized schools to “conform to existing [organizational] norms to an extent that influences them far more than the intentions of their founders” in the interest of obtaining resources from the state (Nygreen 2017a; Nygreen 2017b; O’Donnell 2018; Harding 2012). In this context, I asked: What changes must BPs make to their organizational structure to receive accreditation? How do these structures shape everyday school practices? And finally, what strategies do BPs use to secure state-regulated resources without compromising their core values?

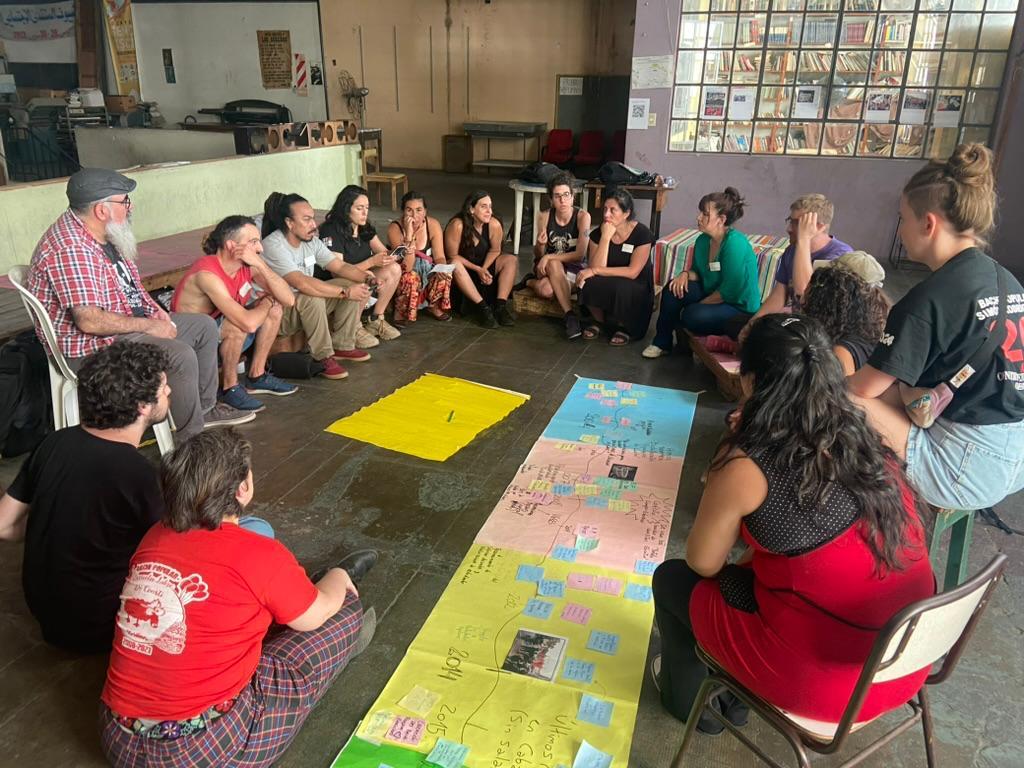

Popular Educators discuss the historical trajectory of BPs at the Annual Workshop for Bachilleratos Populares (Lucas Bricca, 2024)

Principles of Educación Popular

For BPs, K-12 schooling is a “debt of democracy” that the state owes to its citizens, and has failed to repay: over one-third of youth in Argentina do not finish high school by the age of eighteen (Kit 2023). BPs aim to address the vulnerability and super exploitation of non-formally educated people without reverting to the “banking model” of education that characterizes public schooling. Given that entry into and relationships within many modern institutions are conditioned by one’s possession of a high school diploma, the banking model seeks to improve students’ success within existing political-economic structures and relations of power. However, through strict audit culture, competition between students, economic rationalization of school curricula, and the privatization of educational resources, the banking model of education also reproduces those structures and relations (Freire and Macedo 2014; Nygreen 2017b). BPs recognize that merely aiming to guarantee students’ success within an unequal and extractive system can never change the structural causes of their invisibility and oppression. Thus, one fundamental tension of BPs is: What educational practices can address students’ immediate material needs within existing networks of power, while simultaneously changing those networks from below?

“No to the Veto”: University students protest Milei’s defunding of public higher education.

The Double Task of Accreditation

Although many BPs perceive state educational policies primarily as a tool for reproducing the social conditions for capitalist accumulation, there are compelling reasons—such as acquiring accreditation, teacher salaries, or other state-regulated resources—for BPs to create the impression that they are indeed abiding by the government’s policies.1

During my semistructured interviews, I found that one way BPs preserve their organizational autonomy while vying for formal legitimacy is by separating the formal requirements of the state from the everyday activities of the school. For example, for purposes of accreditation, BPs must name a president, secretary, and academic director, roles which imply a hierarchical division of labor. In practice, however, the leadership structure of many BPs remains horizontal, with decisions about the school taken democratically between administrators, teachers, and/or students. Thus, while administrators assume fixed hierarchical roles when engaging with the government, these roles—the adoption of which are a condition for accreditation—have little bearing on the way decisions are made within the school.

In light of the gap I observed between formal and enacted policy in BPs, I characterize the relationship between BPs and the state as “loosely coupled.” In loosely coupled systems, both regulatory agencies and organizations find it beneficial to overlook formally established policies in the interest of upholding public opinion, meeting open-ended goals, and/or achieving demands of production (Meyer and Rowan 1977). Meyer and Rowan argue that modern organizational regulations are not established on the basis of productive efficiency, but rationalized institutional myths. Formal policies, enacted primarily to reify these myths, can undermine organizations’ ability to carry out their day-to-day activities and incentivize them to operate in tacitly accepted violation of formal procedures. For BPs, decoupling is a crucial method for succeeding within existing systems of legitimation while creating structural social change on their own terms.

Under the Radar: Satellite Schools

For many BPs, the focal point of their decades-long historical struggle with the state is the ability to grant diplomas. In order to become accredited institutions, BPs must comply with certain requirements regarding formal teacher training, instruction hours, organizational structure, and curriculum. Here, I focus on the latter two requirements as sites of tension between popular educators’ and the state’s competing visions for schooling.

In regards to the construction of legitimacy, one form of BPs’ organizational resistance stands out from the rest. In what I call the establishment of “satellite schools,” an accredited BP lists students from an unaccredited BP in its enrollment documents. These documents are then submitted to the city government, which effectively officializes titles for students who do not attend accredited high schools.

My research sites were Maderera Córdoba (henceforth Maderera), an accredited BP, and Farmacoop, an unaccredited BP founded in 2022. Farmacoop is a satellite of Maderera, which, each year, includes students from Farmacoop in its student registry. Though the schools are located an hour bus ride away from each other, they have an important historical relationship, and hold regular assemblies together. Thanks to their alliance, despite being an unaccredited BP, Farmacoop’s students graduate with a diploma equal to any other high school. In this way, the BPs distribute a scarce symbolic resource without needing to engage in dealings with the government.

When asked whether the school has received any direct government surveillance, Vicente, a teacher and administrator at Maderera, replied: “It’s a big problem that we all think may happen someday. And we’ll see. So far, they’ve come, but they’ve always stayed at the door.”

Vicente’s testimony raises a crucial question: Is the government aware of this practice? And if so, why don’t they impose stricter oversight to enforce tighter alignment between formal and enacted policy? I interviewed the Director of Adult Education of CABA, but, not wanting to implicate administrators or reveal the extent of the practice to regulators, I struggled to get a straight answer. When I asked the Director about the current state of accreditation, he replied: “I don’t know what goes on at those schools, I just close my eyes and sign their papers.”

One potential explanation for the state’s apparently willing oversight is described in an ethnography by Jennifer Lee O’Donnell, who characterized BPs’ relationship with the state during 2011-2015 as one of fragile alliance. During this period, there was a wave of accreditation in which dozens of BPs were officialized under the UGEE designation, an “experimental education” category that allows BPs to grant diplomas while retaining a great degree of autonomy. Lee O’Donnell argues that, at that time, the government did not perceive BPs antagonistically because it was facing an educational crisis (O’Donnell 2018). Accrediting community-organized schools was a way to increase educational attainment numbers and improve public opinion of the then-administration.

Some BP administrators I interviewed similarly felt that the schools were a symbolic banner for the city government, who, despite not publicly promoting UGEE schools as an option for finishing secondary school, simultaneously uses BPs’ historic gains as evidence of their progressive educational policy. Ricardo, a teacher at Maderera, described it to me thusly:

“Remember, our existence is good for the city government, too… They [the government] say, ‘It's good because in the territories, the people who live there have an educational option.’ And that educational option, if it's formalized, belongs to the city government. Afterwards, behind closed doors, the education belongs to us. We teach how we want to teach.”

Ricardo’s description of Maderera as formally “belonging” to the city government, yet remaining in the hands of educators in practice, exemplifies the BP’s strong decoupling from its regulatory environment. His testimony encapsulates BPs’ tacit agreement with the government: Sign our diplomas; in return, you can talk about supporting the pueblo.

From this interview data, I argue that the observed loose coupling is not the result of a “true” oversight on behalf of the state, but a calculated one. Although some policymakers of the current city government disavow them, UGEE BPs bolster the state’s educational metrics and public optics at little cost. Consequently, the city government benefits more from overlooking BPs’ evasion of formal policy than spending greater resources surveilling them. In the following section, I examine the effects of this calculated oversight in regards to a recent technical education program.

Decoupling as the Result of Contradictory Policy

Last year, CABA updated its adult education curriculum to include an additional technical education component, which, according to teachers and administrators, would come at the cost of courses such as Community Development. The policy affected Maderera, since it is formally accredited, but not Farmacoop. However, Maderera does not have the infrastructure (computers for students, for instance) to support such a program, and the policy does not stipulate any increased resource disbursement for BPs to implement these changes. At Maderera Córdoba, teachers already pool a percent of their monthly salaries just to cover the cost of maintaining their building, classroom, and teaching supplies. Furthermore, Maderera’s budget is even lower than in previous years, since their (along with other BPs’) annual federal stipend (Fondo de Incentivo Docente) was cancelled in 2024. As a result of asking Maderera to implement resource- and labor-intensive reforms under such dire conditions, administrators regarded these policies as illegitimate and disregarded them:

“We're going to pretend that we're going to do it, but we're going to continue with our own thing,” said Vicente. “It’s this thing of saying yes, we're going to do it, but behind closed doors, we do something else.”

Since the policy was not feasible for Maderera to implement, administrators responded by simply carrying on business as usual. Although the state’s intention was to make students more prepared for a digitized world—and international labor market—Maderera’s experience demonstrates that policies putting increased demands on educators while cutting educational resources undermines the legitimacy of those policies. Despite this, the market rationalization of curricula and privatization of educational institutions have historically been carried out in conjunction—notably in Argentina’s educational reform of the 1990s, when the policies also generated a crisis of legitimacy (Carlino 2004).

Through the Technical Education program, policymakers both leveraged and contributed to decoupling from BPs. On one hand, by creating what Maderera felt were unrealistic demands, the policy changes were viewed as illegitimate and administrators insulated the actual school activities from it. On the other hand, by choosing not to enforce BPs’ adherence to the program—or to its accreditation policies at large—the government neatly avoided reckoning with the contradictions of placing increased demands on schools while simultaneously privatizing educational resources. A highly decoupled policy environment allowed the government to turn a blind eye not only to BPs’ negligence, but its own.

Today, the experimental UGEE category stands in contrast to the relatively more institutionalized CENS BPs, which are actively promoted by the current administration. The administration regards UGEE schools as a relic of the center-left government, and the Director of Adult Education told me he has no intentions of officializing any more BPs under the UGEE label. Given the relative marginality of UGEE BPs, as well as the government’s selective endorsement of their CENS counterparts, it is not entirely accurate to say that Maderera and Farmacoop’s strategies of organizational resistance have allowed the schools to meaningfully change their institutional context in the long term. Nor, however, is it the case that these practices are simply subsumed by neoliberal governance structures. Rather, the complex policy relationship between BPs and the state demonstrates, on the one hand, how collective resistance among BPs helps the schools navigate the politics of legitimation, and on the other, why the state benefits from tolerating their resistance to formal policy. Over the last year, a decoupled policy environment has allowed BPs to practice an alternative form of education through their dual horizons of organizational autonomy and survival within existing power structures, while allowing the city government to declare a technological curriculum update without regard for the corresponding resources and support required to carry it out.

Future research on organizational compromises during bachilleratos populares’ institutionalization should focus on the differences in organizational structure between UUGE and CENS schools.

1. Some BPs explicitly do not seek state recognition, so not all BPs are defined by this duality.

Carlino, Florencia. 2004. “Evaluation at the Forefront of the Neoliberal Agenda for Education in Latin America: Disclosing the Contradictions of the Recent Argentine Experience,” August. http://udspace.udel.edu/handle/19716/19540.

Freire, Paulo, and Donaldo P. Macedo. 2014. Pedagogy of the Oppressed: 30th Anniversary Edition. Translated by Myra Bergman Ramos. 30th anniversary edition. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Harding, Tobias. 2012. “How to Establish a Study Association: Isomorphic Pressures on New CSOs Entering a Neo-Corporative Adult Education Field in Sweden.” Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 23 (1): 182–203.

Kit, Irene. 2023. “Índice de resultados escolares: ¿Cuántos estudiantes llegan al final de la secundaria en tiempo y forma?”

Meyer, John W., and Brian Rowan. 1977. “Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony.” American Journal of Sociology 83 (2): 340–63.

Nygreen, Kysa. 2017a. “Negotiating Tensions: Grassroots Organizing, School Reform, and the Paradox of Neoliberal Democracy: The Paradox of Neoliberal Democracy.” Anthropology & Education Quarterly 48 (1): 42–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/aeq.12182.

———. 2017b. “Troubling the Discourse of Both/and: Technologies of Neoliberal Governance in Community-Based Educational Spaces.” Policy Futures in Education 15 (2): 202–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210317705739.

O’Donnell, Jennifer Lee. 2018. “The Promise of Recognition and the Repercussions of Government Intervention: The Transpedagogical Vision of Popular Educators in Buenos Aires, Argentina.” Gender and Education 30 (8): 1078–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2017.1296113.