Race to the Bottom of the Global Knowledge Economy

archive

Race to the Bottom of the Global Knowledge Economy

Two remarkable trends in the global labor economy point in seemingly opposite directions. On the one hand, service industries concentrate in major cities, attracting educated and elite workers, while on the other hand, manufacturers scramble around the world in search of cheap labor and government subsidies. As a result, highly skilled workers tend to cluster in desirable neighborhoods, while factory workers reside in marginal locales where they live with the persistent prospect of layoffs and factory closings. Such globalizing trends have exacerbated tensions in many societies, leaving policymakers with a restricted set of options. The most “visionary” response has been for public opinion leaders to tout the merits of education and infrastructure investments aimed at building bridges to the global “knowledge economy.” Proponents argue that the best jobs of the future will be creative jobs that add distinctive value to products, value that is not easily replicated elsewhere. The biotech and computer industries are emblematic of the knowledge economy, so too are elite service sectors, such as finance, engineering, and law. The most glamorous sector is media and entertainment where Hollywood reigns supreme as a hotbed of creative talent and sophisticated infrastructure, or so it would seem.

Yet in fact Hollywood is wracked by anxieties about the flight of jobs, and nowhere was that more evident than the 2013 Academy Awards where the Oscar for best visual effects went to the Life of Pi. The winning VFX team, Rhythm and Hues, was hired by Fox 2000 Films to create the stunning illusion of a relationship between two castaways at sea, a young man and a fearsome Bengal Tiger, the latter a figment of digital technology. Besides widespread critical acclaim, Life of Pi earned more than $600 million at the global box office and many contend that the true stars of the film were its visual effects.

Accepting the award, Bill Westenhofer expressed appreciation to his creative team and then turned his remarks to the problems confronting effects workers in Hollywood. Yet just as he began, Westenhofer was cut short by a swell of ominous music from the soundtrack of Jaws, the Academy’s signature technique for shutting down acceptance speeches that run up against the time limit. More than four hundred VFX artists protesting outside the ceremonies were incensed by this turn of events and incensed as well by the fact that Rhythm and Hues had filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy only ten days before the Oscars. Renowned as one of the best employers in the effects business, R&H provided its employees pay and benefits that were above the industry norm. Its financial failure was both a sad commentary on the VFX business as a whole and on prospects for the workforce as well. At most effects shops, artists toil long hours under intense deadline pressures and do so without health care, vacation pay, or job security. Increasingly, they are hired for particular projects and terminated when the film is completed. Constantly searching for work, they must be willing to relocate to jobs in distant locales.

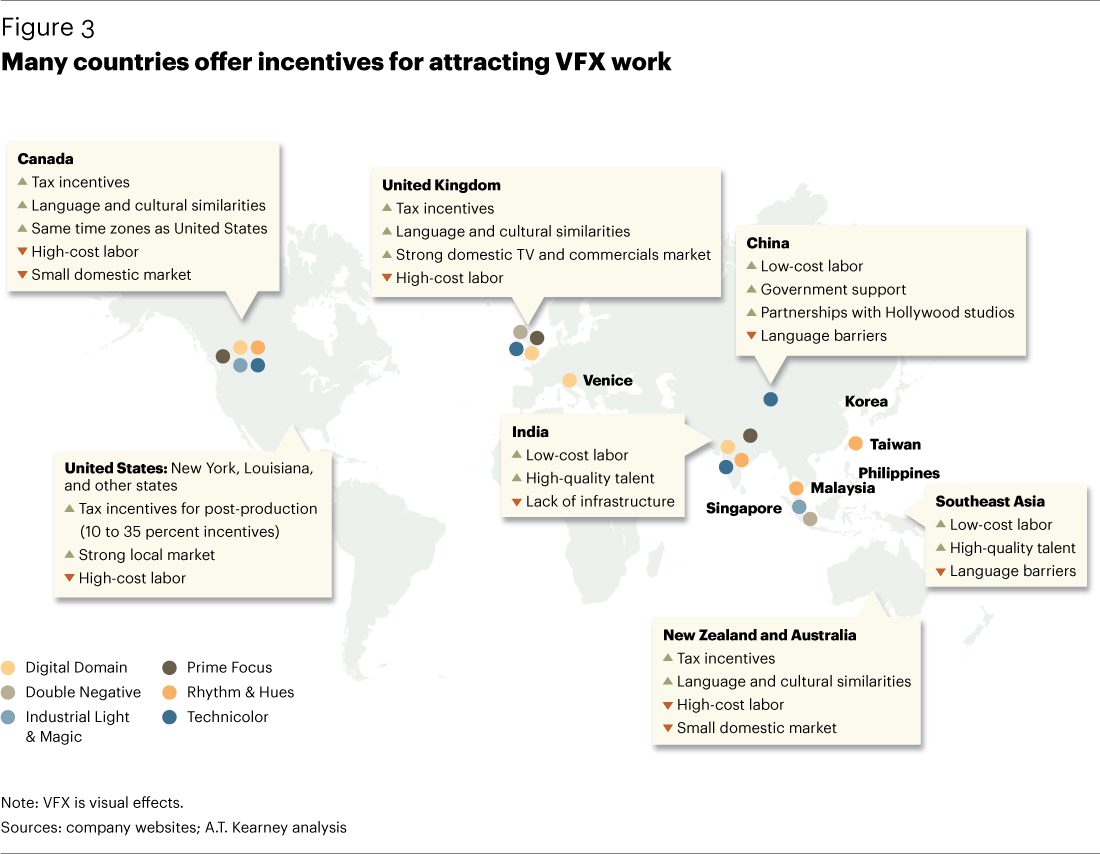

Governments around the globe have been subsidizing the development of VFX, animation, and other digital media businesses, seeing them as keys to future economic growth. Facilities in China, India, and New Zealand confidently assert that they can now compete with Hollywood counterparts in terms of quality and cost. Yet Rhythm and Hues offers a cautionary case example, for the very same pressures and practices that brought the company to its knees are likely to confront its competitors as well.

The key to understanding these challenges is the subcontracting system employed by producers of “tentpole” feature films, such as Skyfall, The Hunger Games, and The Dark Knight Rises. Although they are financed and distributed by major studios, the actual production of each film is conducted by hundreds of employees, most of whom work for independent companies that sign contracts with studio producers to provide specific services at a set price. These contracts are negotiated during the planning stages, well before filming begins, and therefore effects companies must fashion a competitive bid but also one that provides enough leeway for the inevitable revisions that take place during filming and post-production. Such revisions can be driven by creative choices of the director or by decisions made by other talent or executives attached to the project. Yet contracts never include a clause for cost “overages,” nor do they include a profit participation clause that might bring additional revenue to a company that invests extra effort in a film that ultimately becomes a hit.

Under these conditions, executives at companies such as R&H are under constant pressure to bid aggressively against competitors around the world, many of them supported by tax breaks and subsidies from local governments. Some Canadian provinces offer 33 percent tax breaks on VFX production costs. Chinese officials have subsidized the construction of state-of-the-art production facilities. And Indian effects shops enjoy significant labor cost advantages.

Like all independent film and television companies, R&H had to strike a balance between creative excellence and cost containment, but they were forced to do so in a business with very thin profit margins, ranging between 3 and 5 per cent. Consequently there was little room for error and although the company had a long and distinguished track record, it operated under the shadow of financial insolvency. If one or two major projects were cancelled, delayed, or failed, the company could be pushed over the edge.

Such adverse conditions ultimately precipitated the bankruptcy of Rhythm and Hues. According to industry insiders, R&H had been flourishing on revenues flowing from tentpole features for Fox and Universal that brought in roughly $90 million per year. But in 2012, both studios cut back on effects-driven titles, engendering a perfect storm for R&H as its revenues from studio films plummeted to $18 million. Lacking a nest egg from profit participation on successful films of the past, the company ran out of operating cash on the eve of its Academy Award.

Rhythm and Hues offers a cautionary case example, for the very same pressures and practices that brought the company to its knees are likely to confront its competitors as well.

During bankruptcy proceedings, Rhythm and Hues was bought by Prana Studios, which is backed by a group of Bollywood investors. One source claims that although R&H will continue its LA operations, some 80 percent of production is likely to be conducted overseas. This will no doubt give a boost to Asian competitors, but it casts a pall over the business as a whole, as VFX shops in Asia are likely to face the very same challenges going forward. Workers find themselves in an equally tenuous situation. In recent years, many in LA have decamped to jobs overseas where in some cases they are training workers who will eventually replace them. Meanwhile, artists in the UK and Canada worry that they will lose work if government subsidies evaporate, while those in Mumbai and Shenzhen face persistent pressure to hold down pay and benefits. All VFX workers are confronting demands for longer and often unpaid work hours, especially during “crunch times” that precede the release of a major movie. Although highly skilled and creative, many VFX workers no longer share the heady optimism expressed by proponents of the global knowledge economy. Indeed, many now contend that regulation and labor organizing may offer the best hopes for their future.