Could Millennials Reshape Global Supply Chains?

archive

Could Millennials Reshape Global Supply Chains?

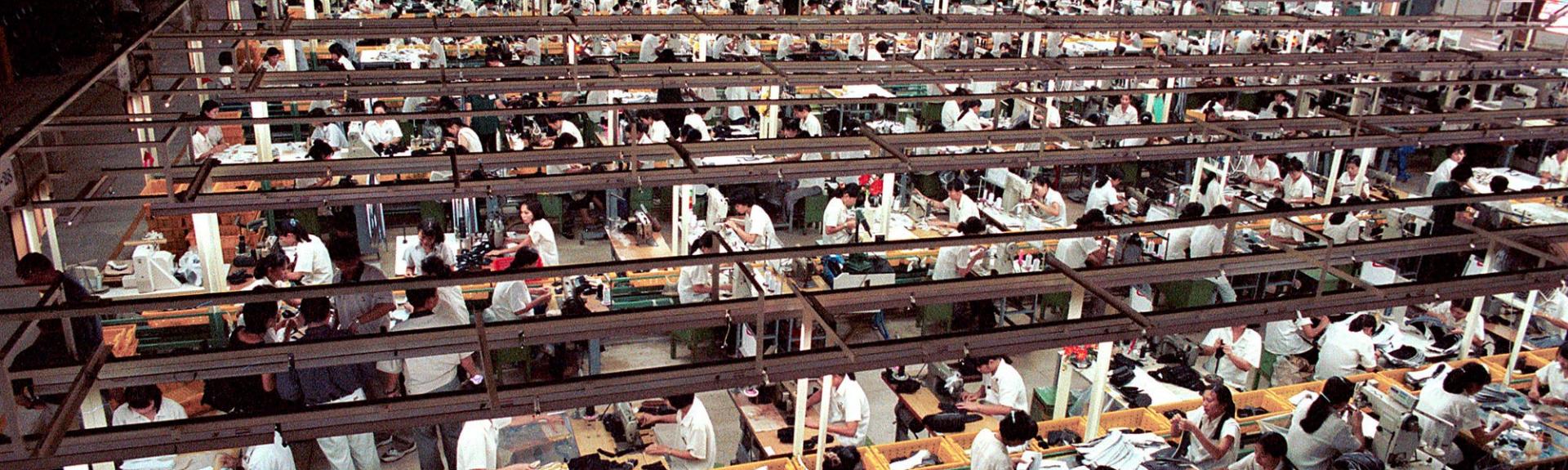

In April 2013, more than 1,100 workers were killed in Dhaka, Bangladesh when the Rana Plaza garment factory collapsed. This tragedy seemed poised to be the catalyst for a global reimagining of clothing production. But after only a week, the strikes in Bangladesh resulting from the tragedy subsided and global news coverage grew quiet. Why so little engagement?

The challenges posed by production and consumption on a global scale are on the one hand easy to see, as vividly exemplified by the Rana Plaza incident, but the causal issues are concealed behind layers of intermediaries, various national and international regulations, and a dizzying number of ethical labels and campaigns. In this essay I will try to illuminate the current structural problems of global supply chains before turning to how consumers, and particularly millennials, can effect positive change.

Structural Problems in Reforming Global Apparel Production

During the 1990s, activists and unionists around the globe brought to light inequalities and exploitation in the global apparel industry. Early on, their attention focused on how US trade policy facilitated the movement of factories overseas, which changed the power relations of production that had been in place since the early 20th century, following the death of 146 female garment workers in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire in New York City in 1911.1 This event provoked a wave of anti-sweatshop activism, leading to the formation of a tripartite system of bargaining involving capital, labor, and the state. Today, Appelbaum and Lichtenstein argue, capital remains in the form of brands and suppliers, but as production globalized in the 1990s and early 2000s, the state and labor disappeared from this arrangement. Weak unions and states with little enforcement power gave way to two new players: consumers and NGOS hired to monitor supply chains.2 This new arrangement, in many cases, gives owners of capital the ability to reshape manufacturing to their benefit. As The Guardian reported, for instance, the owner of Rana Plaza had several stories illegally added to the original building despite the fact that the structure was built on soft, swampy land not zoned for industrial use. Without strong state institutions or worker’s organizations to ensure safe working conditions, the owner of Rana Plaza remodeled with impunity, putting profits ahead of worker safety.

So what can be done about this unequal playing field?

Closing down sweatshops may seem like the most effective response to safety concerns and the myriad other problems often associated with global production. However, some argue that these low-wage manufacturing jobs lift people out of poverty in places like Bangladesh or Indonesia, even when such work takes place under sweatshop conditions. Nicholas Kristof stated as much in 2009, when he visited women and children in Vietnam sorting trash at the local dump who idealized factory work as safe, clean, and well paid. On a national scale, the U.S. garment industry has also fueled the growth of some Southeast and South Asian economies, such as Cambodia listed in a recent Forbes article, helping to provide resources for much needed development.

Instead of shutting down sweatshops, then, others have suggested enforcing more stringent international manufacturing regulations. But this too is complicated, as brands rarely own the factories that produce goods bearing their names. This separation between production and retail means that brands are often unable to track their whole supply chain, and at times do not take responsibility for conditions at production sites.3 In the wake of the Rana Plaza collapse, for instance, the Economist reported that apparel from the British brand Primark and Canada’s Loblaw was found among the rubble, but many other clothing items could not be linked back to a specific brand or retailer.

Without strong state institutions or worker’s organizations to ensure safe working conditions, the owner of Rana Plaza remodeled with impunity, putting profits ahead of worker safety.

Following this tragedy, stakeholders moved to address these issues through two new initiatives. The first, the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh, is a binding agreement between brands and NGOs that requires brands to monitor safety in factories that produce goods for them and oversee building maintenance and improvements. This includes independent audits and a commitment to improve, instead of leave, struggling factories.4 This contrasts strongly with the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, which does not include a binding agreement between brands, NGOs, and manufacturers. Led by two major retailers that refused to sign the Accord, the Alliance relies on self-policing among brands. As Appelbaum argues, a key problem with self-regulation is that the process is internal—that is, results from inspections need not be made public. Consequently, self-regulation results in a “trust me” approach, even though stakeholders often are not guaranteed full access to conditions on the ground.5

Structural Reform through Consumer Action

Instead of solely relying on brands and NGOs to make change, or waiting for the state or organized labor to return, there is another avenue: consumer action. To be clear: this is not a perfect solution. Unlike reforming policy or more stringent regulation, there is no enforcement mechanism to change individual behavior. Some further argue that, in contrast to citizen activity that is political and collective, meaningful consumer reform is unlikely because markets are apolitical and consumption is an individual act. However, Margaret Willis and Juliet Schor argue against this “consumer-citizen dichotomy,” showing instead how politicized consumption is connected to political activism and mobilization.6 In a small study, the authors found that 25% of their conscious consumers were converted to activists after taking part in market-based action.7 Additionally, in larger samples, conscientious consumerism is sometimes positively correlated, and never negatively correlated, with political engagement.8 This suggests being a conscientious consumer does not hurt political engagement, and can instead serve as a pathway to collective action.

However, motivating ethical consumption is not always straightforward. As highlighted in a recent Guardian article, consumers’ “willful ignorance” of ethical information helps them avoid finding out about poor labor practices and feeling bad. Others argue that too much information, provided by ecolabels or services like GoodGuide, overwhelms consumers.9 However, this does not align with emerging research on millennials’ preferences. A 2016 report found that unlike earlier generations, they are suspicious of messages from traditional advertising and want to research products and services in order to develop their own opinions. Instead of overwhelming consumers, this information-rich environment may be exactly what millennials desire in order to make informed choices. Although they may be making an individual consumer decision, many see themselves as pushing to change the system through their purchasing habits. This is evidenced in their support of companies that emphasize transparency in their supply chains.10 Notably, a 2016 article in Food Business News noted that 52% of American parents who purchase organic food are millennials, compared to 35% of Generation Xers and 14% of Baby Boomers.

Instead of solely relying on brands and NGOs to make change, or waiting for the state or organized labor to return, there is another avenue: consumer action.

Students have a special role to play within the larger cohort of millennials. While the dispersion in regulatory oversight has largely excluded labor organizations and the state from intervening, this has allowed activists, such as students, to push for change from the ground up. As an op-ed writer from UCLA’s student-run paper, points out, “Every national campaign against apparel companies has begun with, or been strengthened by, the efforts of ethically conscious students.” Notably, students spearheaded a seminal national anti-sweatshop movement in the late 1990s beginning with a sit-in at Duke University, with actions eventually spreading to hundreds of universities.11

More recently, in the mid-2000s University of California students successfully changed university-purchasing policies mandating that all UC-licensed apparel be produced in ‘sweatshop free’ facilities.12 Additionally, in 2015 United Students Against Sweatshops at UCSB collected 2,000 signatures and rallied other campus organizations demanding that Jansport products be removed from the University bookstore. Jansport is a subsidiary of VF, which regularly contracted with Rana Plaza and refused to sign onto the Bangladesh Accord. As reported by the campus newspaper, UCSB agreed to stop selling Jansport apparel, with the exception of backpacks until the bookstore found a comparable substitute. In adopting the Accord at UCSB, students demanded transparency about the goods sold on campus and accountability from the manufacturers who produce them.

SACOM activists at a January 2015 press conference in Tokyo.

Students are optimistic that the current system of global production can be changed, even if it is at times overwhelming to imagine exactly how. Actions on UC campuses over the past decade around ethical sourcing demonstrate that many students are involved in supply chain activism. Beyond the UC system, this student movement continues to win battles for worker’s rights more broadly. Notably, the Worker Rights Consortium (WRC) grew out of the student anti-sweatshop movement that now comprises 180 formally affiliated colleges and universities.13 Established in 2000, the WRC is an independent labor rights monitoring organization that conducts investigations and supports worker rights campaigns.

A separate campaign waged by U.S.-based students and Dominican workers reopened a shuttered factory, Alta Gracia in the Dominican Republic, which now features an energetic union and fair wages.14 Students have also been active on these issues in other regions. Notably, the non-profit Students and Scholars Against Corporate Misbehavior (SACOM) emerged in 2005 in Hong Kong, building off a student movement focused on local labor conditions, and has now expanded to tackle both local and global labor issues.15

Ultimately, reforming global production is much more than an academic pursuit, as evidenced by the diverse strategies students use to pressure universities to change their policies and broader reform goals. If millennials retain this commitment to their convictions, the next decades may well see substantial reforms of global supply chains, ensuring the safety and well-being of workers through consumer-driven pressure on global manufacturing practices.

1 Tim Bartley, Sebastian Koos, Hiram Samel, Gustavo Setrini, and Nik Summers,

(Bloomington and Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University Press, 2015), 154.

2 Richard P. Appelbaum and Nelson Lichtenstein, eds. Achieving Worker’s Rights

3 Richard P. Appelbaum and Gary Gereffi, “Power and Profits in the Apparel Commodity

Bonacich, Lucie Chen, Norma Chinchilla, Norma Hamilton, and Paul Ong (Philadelphia,

PA: Temple University Press, 1994), 42-62.

4 Bangladesh Accord Foundation, 2015 Annual Report, January 26, 2017.

5 Richard P. Appelbaum, “From Public Regulation to Private Enforcement: How CSR

6 Margaret Willis and Juliet B. Schor, “Does Changing a Light Bulb Lead to Changing

Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 644, Iss. 1, 162-164.

7 Juliet B. Schor essay in Dana O’Rourke, Shopping for Good (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT

8 Bartley et al., Looking Behind the Label, 78.

9 For an example of a critique of consumer-oriented strategies, see Scott Nova’s essay

10 Kelsey Chong, “Millennials and the Rising Demand for Corporate Social Responsibility,”

accessed June 9, 2017. http://cmr.berkeley.edu/blog/2017/1/millennials-and-csr/

11 Peter Dreier, “The Campus Anti-Sweatshop Movement,” The American Prospect,

12 “UC Adopts New Apparel Policy,” Daily Nexus (UCSB), May 19, 2006, accessed

13 Wimberly, Dale W., Meredith A. Katz & John Paul Mason, “Systemic Advantages for

14 Allie Robins, “The Future of the Student Anti-Sweatshop Movement: Providing Access

no. 1 (2013), 149.

15 Pun Ngai, Shen Yuan, Guo Yuhua, Lu Huilin, Jenny Chan and Mark Selden, “Apple,

Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 17, no. 2 (2016), 168.