The Silk Road as Global Imaginary

archive

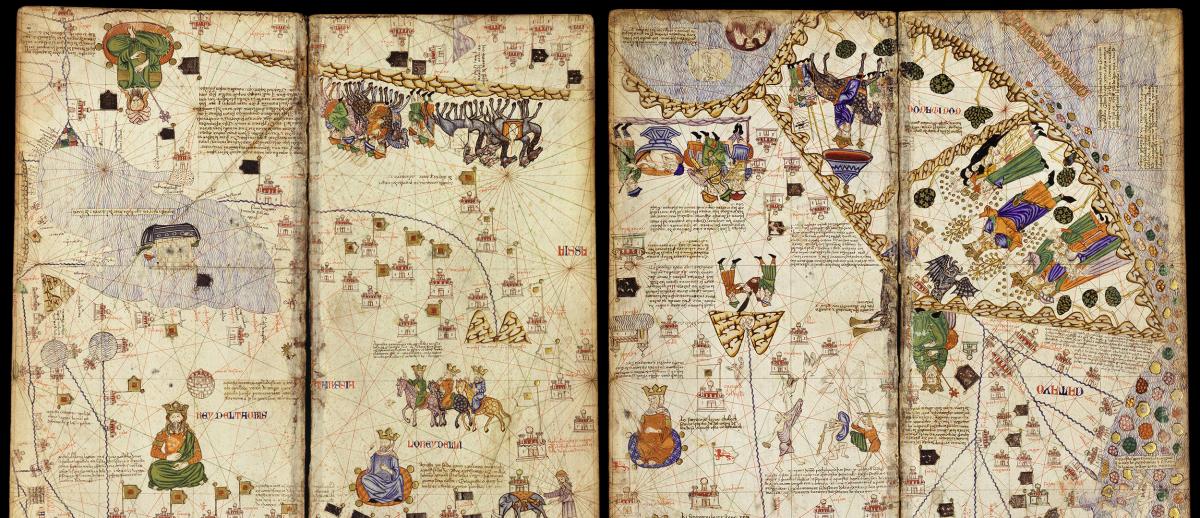

Catalan Atlas depiction of the Silk Road (Source: National Palace Museum Taipei)

The Silk Road as Global Imaginary

When Edward Said first introduced the concept of “imagined geographies,” he never wished the term to imply something false or simply made-up. For Said, the act of imagination was rather synonymous with the act of perception—one that is constructed on a national level (similar to Benedict Anderson’s seminal remarks on “imagined communities”) but which is also applied regionally and, most importantly, globally. Imagination, myth, and fantasy have animated national identities and commerce and have sustained capital accumulation through geopolitical and geo-economic plans that fuse policy and ideation in producing and repurposing the topographical terrain.

This process, which builds from and extends the realm of fiction in order to commodify and politicize natural human habitats, is what produces, I argue, a global imaginary. In doing so, the geophysical space, with economic globalization rhetoric inscribed onto it, becomes both animated and constructed by what is hidden beyond the level of conscious thought—symbols, myths, and cultural artifacts that are usually frowned upon by researchers who still believe that culture as a unit of analysis is inferior to a “hard” dataset.

Lands In-Between

Land is neither a simple concept nor a mere physical entity despite how it naively appears. It not only generates notions of terrain, borders, territories, and regions; land has historically been thought of as a universal good, a space where crops can be grown and factories built. Land becomes a central preoccupation of human affairs inasmuch as it allows people to relate to their environments in new ways, a backdrop for human progression through time.

Trading routes have always generated vivid images of ancient connectivity due to their geopolitical and geo-cultural significance, especially for those wishing to prove that transcontinental land trade is a panacea for all ills. In Asia and the West, the so-called Silk Road became a vivid expression of this phenomenon. Operating as a pro-globalization rhetoric, the routes that became known as the Silk Road emerged during the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD) and stretched throughout much of Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. Yet, to this day, the notion itself evokes a sense of universal familiarity. No matter one’s culture, location, or religion, the Silk Road brings to mind the images of Oriental riches, prosperous oases, and burgeoning trade.

Ferdinand von Richthofen (Courtesy: University of Trier)

We should remind ourselves that the Silk Road extends far beyond the Oriental tales we are all familiar with of travelers crossing the Central Asian steppes on camels. As a concept, as an imaginary, the Silk Road has been an intrinsic product of Western imperial ambitions. Ever since the Prussian geologist Ferdinand von Richthofen embarked on a mission to catalogue Chinese natural resources and coined the term “Silk Road” (Die Seidenstraße) in 1877—epitomizing what we now refer to as ancient globalization—he replicated the worldly fantasies of wealth, prosperity, and power of generations before him.

Once it received this name, the Silk Road became “revivable,” allowing later engineers and technocrats to plot onto it their visions of ambitious futures to come. The Silk Road became a land in-between in the sense that it refers both to a period of antiquity that is considered a historical fact and to a form of discourse which carries real socio-political

consequences. Suspended in time and caught between often clashing, yet similar, ways of imagining the “Other,” the Silk Road not only facilitated commercial and cultural exchange but also symbolized the appetite for foreign cultures, lands, and commodities, bridged distant geographies, and thus opened out unimaginable possibilities.

As an invitation to strive for what lies beyond prevailing borders of possibility, the Silk Road escapes historical frames, becomes more than a historical fact of commercial, political, and cultural significance. It is what Jacques Lacan would call an imago, a culturally and mentally constructed space of experiences, narratives, and images,1 which prompts us to reconsider our popular understanding of the term and instead frame it as a nonlinear, irregular, and complex flow of meanings and exchanges—corporeal and immaterial.

This exchange of people, ideas, and cultural artifacts—which obviously went together with conquest and the spread of disease—has ingrained itself in popular consciousness. Today, it would be difficult to imagine the world without the “Silk Road”—not the space, but the ‘brand’ that is used by cultural heritage organizations, music ensembles, fashion shows, restaurants, tourist agencies, and political projects. Yet while we recognize that the Silk Road has provided an iconic historical backdrop for tales of exchange and of victories and conquests, we too rarely interrogate the rhetorical appeal and cultural power of concepts such as the Silk Road.2

As an invitation to strive for what lies beyond prevailing borders of possibility, the Silk Road escapes historical frames, becomes more than a historical fact.

Having generated and continuing to generate powerful symbols of encounter and connectivity, the Silk Road remains an imaginary geography, a land in-between, that enables us to observe the constant use of historical symbolism, patterns, and models as embedded not just in discourse but in both artistic and material production. These symbols beg the question: how does the Silk Road imaginary materialize itself in global spaces of today? How does it continue to function as a powerful discourse?

Landscapes of Possibility

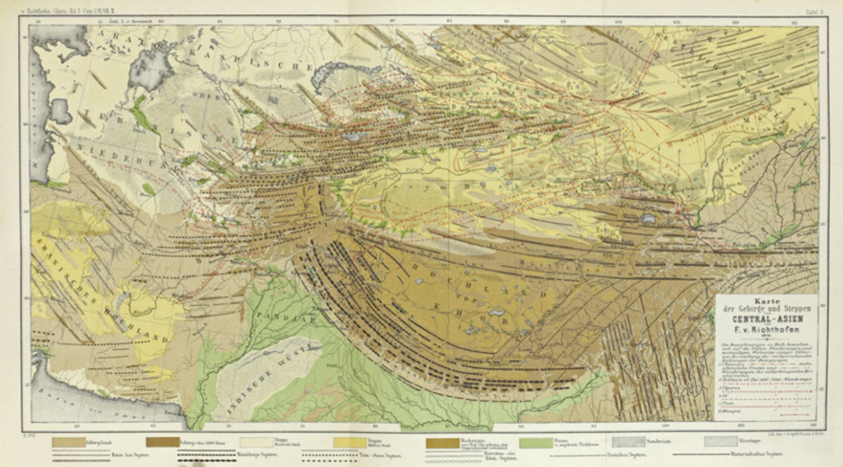

During his fieldwork in China, Richthofen became astounded by the country’s vast natural resources, leading him to publish extensively on his discoveries. In his work he presented an elaborate plan of extracting coal from China’s rich deposits as well as building a transregional railway “from the German sphere of influence in Shandong through the coalfields near Xi’an all the way to Germany.”3 Richthofen’s imperial fantasy was presented as the preferred means of Chinese modernization through capitalization of the natural landscape.

"Overview of Transport-Connections from 128 BC to 150 AD" by Ferdinand von Richthofen.

Though initially rejected, these ideas resurfaced in the late 19th century when a Chinese reformer, Zheng Guanying (1842–1922), indirectly cited Richthofen’s work when arguing in 1892 that major empires relied on mineral resources to attain wealth, power, and prosperity. As history unraveled, China’s march toward industrial modernity was indeed paved with coal. It is difficult not to draw parallels between Richthofen’s geostrategic experiments in China and his experiences as a young geologist in the American West—where, having worked in Northern California and Nevada in 1862, he experienced first-hand the power of speculative capitalism and the allure of mineral wealth.

Richthofen’s work was published during a time of unprecedented global ambitions driven by technological optimism and railroad visionaries. In the Americas, the Canadian Pacific Railway was being completed in 1885 and it already projected the future of Vancouver as a global city, while in 1893 the Great Northern Railway was being finalized. The Trans-Siberian Railroad was being planned, Cecil Rhodes promoted his imperial vision of a Cape-to-Cairo railroad, and the Spanish architect, Arturo Soria y Mata, contemplated a vast linear city stretching from Cádiz to St. Petersburg. These projects attempted to push the frontiers of the possible for land-based connectivity. Their rhetorical power has often been overlooked, yet their legacy of utilizing powerful cultural signs to alter the make-up of the geophysical terrain has only grown stronger with time.

These symbols beg the question: how does the Silk Road imaginary materialize itself in global spaces of today?

Richthofen’s geo-vision did not come to fruition in his lifetime. However, the idea of hard-wired Sino-Western connection animated by cultural myths, and powered by extractive capitalism and modern commerce, became a blueprint that finally did materialize the imagined. After all, as Ciara Bottici reminds us, nothing can be represented or materialized before it is conceptualized or imagined.4 Richthofen’s dream would eventually serve as a model for China’s trillion-dollar vision known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which represents itself as the revival or restoration of a 2,000-year-old civilizational order.

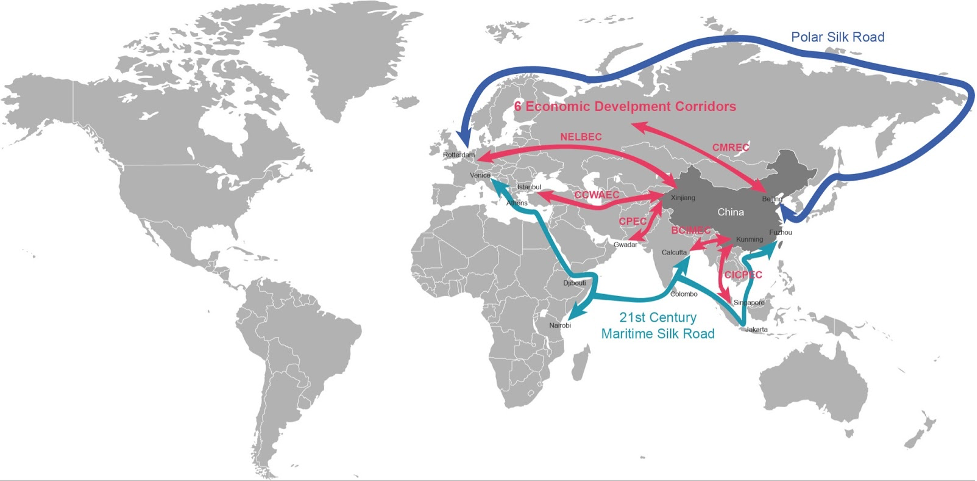

The China-financed BRI presents a vision of a global infrastructure network that extends the scope of the original Silk Road. Announced in 2013, BRI includes the Silk Road Economic Belt stretching across the Central Asian landmass, and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road (CMSR), which mirrors the journeys of Admiral Zheng He. Moreover, BRI extends its operational scope to non-Silk Road regions as well as into the digital sphere and even public health, which allows us to see BRI as operating ideologically by wooing and gaining acceptance through powerful ideas of peaceful relations, wealth, prosperity, and opportunity.

Belt and Road Initiative (Courtesy: BeltRoad-Initiative.com)

In doing so, the Silk Road imaginary weaves together the incomplete memory of the past and the anticipations and aspirations of the future by transforming global cultural heritage into an intoxicating script—a global imaginary. Its mobilizing force acts in similar ways to the “Make America Great Again” slogan, yet its representational modalities offer more depth by pointing to a universal icon of the Silk Road that is cross-culturally understood and internationally-desired. It projects, materializes,5 and justifies the very ideas associated with its own romantic past—unfettered ambitions, unimpeded trade, prosperity for all—wrapped in the promise of inclusive globalization, mutual benefits, and increased connectivity.

1. Boothby, R. 2014. Death and Desire (RLE: Lacan): Psychoanalytic Theory in Lacan’s Return to Freud, London: Routledge, p. 25; Lee, J.S., 1990. Jacques Lacan. Woodbridge, CT: Twayne Publishers, p. 14.

2. Winter, T. 2019. Geocultural Power: China’s Quest to Revive the Silk Roads for the Twenty-First Century, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

3. Hansen, V. 2016. The Silk Road: A New History with Documents, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 8.

4. Bottici, C. 2014. Imaginal Politics: Images Beyond Imagination and the Imaginary, New York: Columbia University Press, p. 90.

5. Meinig, D.W., 1979. The beholding eye: Ten versions of the same scene. The interpretation of ordinary landscapes: Geographical essays, pp.33-48; Mitchell, W.J.T. and Mitchell, W.J.T. eds., 2002. Landscape and power, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.