The UN Alliance of Civilizations: Contributing to improved inter-civilizational relations?

archive

The UN Alliance of Civilizations: Contributing to improved inter-civilizational relations?

Nearly two decades after 9/11, the United Nations (UN) is floundering when it comes to the burning question of how can we all get along together in this shrinking, interconnected, competitive, increasingly dysfunctional global environment. When the UN began its work nearly three quarters of a century ago, things seemed clear: we had seen off the scourge of fascism and extreme nationalism and now we could forge ways to work together towards mutually agreed collective goals of stability, security, development and human rights. Soon after the UN’s founding, however, the eruption of the Cold War and a contemporaneous decolonization process in Africa, Asia, the Middle East and the Caribbean coalesced to provide unexpectedly unstable international relations. Fast forward a few decades: decolonization is over and so is the Soviet Union. The 1990s ushered in globalization, democratization, and neo-liberal economic pipedreams of stability, security, and progress for all. Viva la révolution! Then out of the blue came 9/11, both literally and metaphorically. ‘Civilizations’ were suddenly in vogue, thanks in part to Huntington’s influential left-field analysis of international relations.1 How to stop us killing each other, when we identify with different civilizational traditions and mores? What was the UN going to do about it? The answer came in 2005, following al-Qaeda-inspired operatives’ bombing of Madrid’s train system, which killed 192 people and injured around 2,000 on 11 March 2004 (known in Spain as 11-M), three days before Spain’s general elections. The prime ministers of (Christian) Spain and (Muslim) Turkey jointly lobbied the UN General Assembly to set up an entity to focus on inter-civilizational discord. Following a ‘political initiative’ of the then UN Secretary General, Kofi Annan, the UN Alliance of Civilizations (UNAOC) was born, setting up shop in 2007. After a decade, what’s its track record?

The UNAOC was established to achieve improved inter-civilizational dialogue between the West and the Muslim world, with a view to curtailing atrocities like 9/11 and 11-M. Surely, it was posited, if we talk more to each other and get to know what our hopes and fears are, then, as rational people, we can work out ways to improve things and undermine the violent extremists and terrorists. To achieve these goals, however, would require effective, sustained, and meaningful efforts. Both elites and non-elites would need to be involved. In short, the UNAOC’s overall aim was to address issues of collective inter-civilizational concern, finding a modus vivendi in the face of what many saw as increasing polarization. The UNAOC would be the UN’s attempt to create and develop a global governance mechanism devoted to dealing with the issue of inter-civilizational dissonance.

But this raises another issue about the UN and its real or imagined leadership of the ‘global community’. Spain and Turkey are two middle-ranking countries that several recent global-e authors, such as Turkey’s former foreign and prime minister, Ahmet Davutoğlu, point to good prospects for a new era of leadership in international relations. Does leadership of the UNAOC take this aim forward?

For the last two years, I have been looking into the UNAOC and ‘inter-cultural dialogue’, in a research project funded by the John Templeton Foundation.2 My initial hypothesis was that the UNAOC is a well-meaning, elite-sponsored initiative that would nevertheless struggle to achieve its goal of improved inter-civilizational relations between the west and the Muslim world. I saw four main concerns. First, does the UNAOC have enough in the way of inspirational leadership, funding, and infrastructural support to make possible the achievement of its lofty aspirations?

Source: UN News Centre

Second, does the UNAOC ‘only’ engage primarily in ‘symbolic politics’; that is, does it seek to create a more open atmosphere for ‘better’ dialogue among Christian and Muslim elites, while failing to appreciate the diverse and complicated contexts in which tensions arise?

Third, could the UNAOC develop a framework that was comprehensive and flexible enough to facilitate both inter-elite and grassroots interactions in the Christian and Muslim worlds and, as a result, undermine the violent extremists and terrorists? Fourth, under the leadership of Spain and Turkey, is the UNAOC able to lead the UN into purposeful and effective intercultural dialogue?

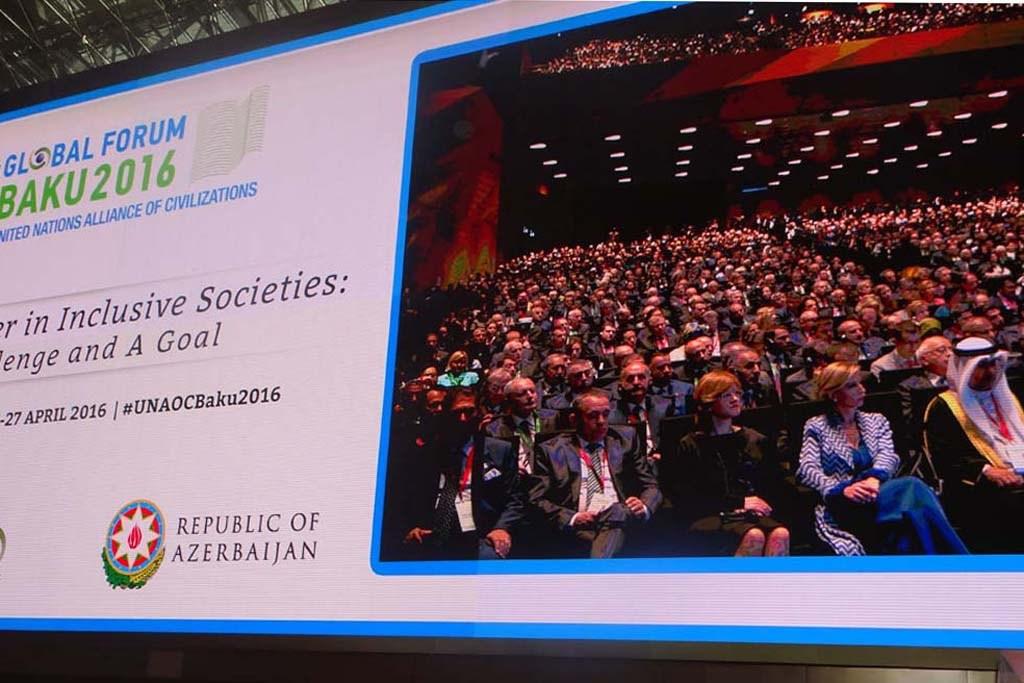

The Alliance concentrates on big, headline events, notably the ‘Global Forum’, which brings together 3,000-4,000 interested people from government, international organizations, non-governmental organizations, business and academia. The initial Global Forum (Madrid, 2008), was followed by six others: Istanbul (2009), Rio de Janeiro (2010), Doha (2011), Vienna (2013), Bali (2014), and Baku (2016). Initially envisaged as annual events, the Global Forum now fluctuates between being held each year and taking place biennially. The problem is that potential Global Forum funders—which would come from the UNAOC’s 146-member ‘Group of Friends’ (120 states and 26 international organizations)—seem increasingly unwilling to provide the necessary $3 million to fund the event. Why? Because it is not clear that Global Forums are valuable.

The UNAOC would be the UN’s attempt to create and develop a global governance mechanism devoted to dealing with the issue of inter-civilizational dissonance.

In addition to the Global Forum, the Alliance oversees eight ‘Special Projects’, covering four topics: Education, Youth, Migration, and Media. The Special Projects are paid for by various funders, including governments and business. In addition, the Alliance ran annual Summer Schools until 2015, in conjunction with EF Education First, a private, for-profit, international education company. The Summer Schools each had “75-100 participants aged 18-35 [who] engage in workshops, roundtables and collaborative work focused on fostering diversity and global citizenship; reducing stereotypes and identity-based tensions; promoting intercultural harmony and social justice.”3 Other Special Projects include the ‘Intercultural Innovation Award’ and ‘Intercultural Leaders Award’ (both run in partnership with the German luxury car business, BMW Group); several initiatives devoted to enhanced ‘Media and Information Literacy’; the ‘Plural + Youth Video Festival’ (run in conjunction with the UN’s International Migration Organisation); the UNAOC Fellowship Programme, which brings together young people from both the West and the Muslim world to share experiences; the Youth Solidarity Fund, which provides seed funding to outstanding youth-led initiatives that promote long-term constructive relationships between people from diverse cultural and religious backgrounds, and the annual ‘Hate Speech Conference’ focusing on how to reduce hate speech in the media.

Source: UNAOC

The overall impact of the Special Projects is hard to gauge. What is clear, however, is that the capacity of the Alliance is seriously undermined by its constant struggle for funds. The UN provides no money; all of the Alliance’s income must come from voluntary contributions that average a modest $3-4 million dollars a year, just about sufficient to pay for the Alliance’s 15-20 person Secretariat and office space near the UN headquarters in mid-town Manhattan. Turkey and Spain provide funds, but not enough to make the Alliance financially secure.

What, then, is the Alliance for? It wants to be a ‘soft’ power tool, different from the ‘hard’ power of military and economic clout, working to find common inter-civilizational ground against violent extremism and terrorism. But even if there is a center ground where ‘representatives’ from the Christian and Muslim worlds can agree on the way forward, as Spain and Turkey envisage, would this sufficiently undermine the hard men and women and their murderous activities?

The difficult trick is to establish, develop and consolidate a set of values and beliefs based on the UN Charter of Human Rights, as a basis for shared understandings of the world and a template for what is appropriate and what is simply wrong. The Alliance wants to enhance the lives of those on the sharp end of civilizational enmity via stakeholders working closely and flexibly together pursuing consensual goals towards improved global governance. But in these days of seemingly growing inter-cultural and inter-religious tensions in Europe, the USA, and elsewhere, the grotesque phenomenon of Daesh/Islamic State, and the tragedy of the expanding global refugee crisis, the need for the Alliance to up its game is clear.

It wants to be a ‘soft’ power tool… But even if there is a center ground where ‘representatives’ from the Christian and Muslim worlds can agree on the way forward [,] would this sufficiently undermine the hard men and women and their murderous activities?

But who or what will provide the impetus? Both Spain and Turkey have their own problems, and seem content to let the Alliance drift on, emblematic of their dwindling effectiveness in becoming growing powers at the UN. Yet the Alliance remains a potentially viable framework for improving inter-civilizational relations. On the plus side, the UN now has more inter-civilizational dialogue than before, while most agree on the importance of the Alliance’s four pillars: Education, Youth, Migration, and Media. On the other hand, the UNAOC’s objective of bringing together governments, international organizations, and civil society organizations is not being realized, undermined by financial, organizational and policy-related weaknesses.

Thus, after a decade, progress is problematic for the Alliance, held back by three main factors: (1) less-than-inspirational leadership, insufficient and precarious funding, and a lack of support and encouragement from other UN organizations, (2) failure to bring together elites and non-elites in a coherent decision-making environment that suits its purpose, and (3) a sense that years after 9/11 and 11-M the search for improved inter-civilizational relations is being overtaken by other, more topical concerns, such as fixing the global economy, mediating US-North Korea relations, and ending debilitating regional wars in Syria and elsewhere. Finally, if Spain and Turkey still envisage the Alliance as their ‘flagship’ entry into the UN’s big league, they need urgently to put their money and diplomatic clout where their mouth is to ensure that the Alliance doesn’t go the way of other failed UN initiatives.

1 Samuel Huntington, "The Clash of Civilizations?" Foreign Affairs, 72 (3), 22-49, 2003, and

2 Details about the Enhancing Life Project can be found at:

3 UNAOC, ‘Summer Schools’ information here:

Bettiza, Gregorio (2014) "Empty Signifier in Practice: Interrogating the 'Civilizations' of

Goff, Patricia M. (2015) "Public diplomacy at the global level: The Alliance of Civilizations

Haynes, Jeffrey (2017). "The United Nations Alliance of Civilizations and Global Justice."