Afro-Reggae Soundscapes: The Communicative Power of Music

archive

screenshot of video for the song 'Satati' by Momar Gaye and band Zaman, on beach in Sardinia, Italy

Afro-Reggae Soundscapes: The Communicative Power of Music

One of today’s most pressing global challenges is to foster communities that are at once trusting, welcoming, and cohesive while also embracing cultural and linguistic diversity. Illustrative of this point is the following story. In February 2018, neo-Nazi Luca Traini opened fire on 6 migrants hailing from Nigeria, Ghana, Gambia, and Mali in the Italian city of Macerata. The previous year, Traini had been an unsuccessful candidate in the local elections for the anti-immigrant party, Lega. Lega rose to power the following month in the Italian general election, forming a populist coalition with Movimento 5 Stelle. Just one day after the elections, Idy Diene—a 54-year-old street vendor who had migrated to Italy from Senegal 20 years prior—was murdered in Florence by Roberto Pirrone, a white Italian male. While police ruled out a racist motive for the shooting, the local Senegalese community vehemently protested what they believed to be a prejudicial attack, blaming the divisive climate and rhetoric of the preceding election campaign. Tragically, in December 2011, Diene’s cousin had been murdered along with another Senegalese citizen at the Florence market where they worked; the murderer was a neo-fascist, Gianluca Casseri.

During this fraught period, Senegalese Afro-reggae musician and President of the Sardinian Senegalese community’s Cultural Commission, Momar Gaye, exalted music as the most significant force for integration. In a 2017 television interview, Gaye described music as a “universal language” with the capacity to “open a gateway” to integration and understanding between newly arrived and host communities. Gaye was speaking from experience. Some 17 years earlier he had been forced to migrate from Senegal to Sardinia, Italy, via France, transplanting his musical career from his homeland to new cultural and linguistic terrain. In 2002, he re-established his band, Zaman, in Cagliari with local Senegalese and Sardinian musicians to create what they refer to as “one of the best examples of music and integration present in the Italian landscape.”

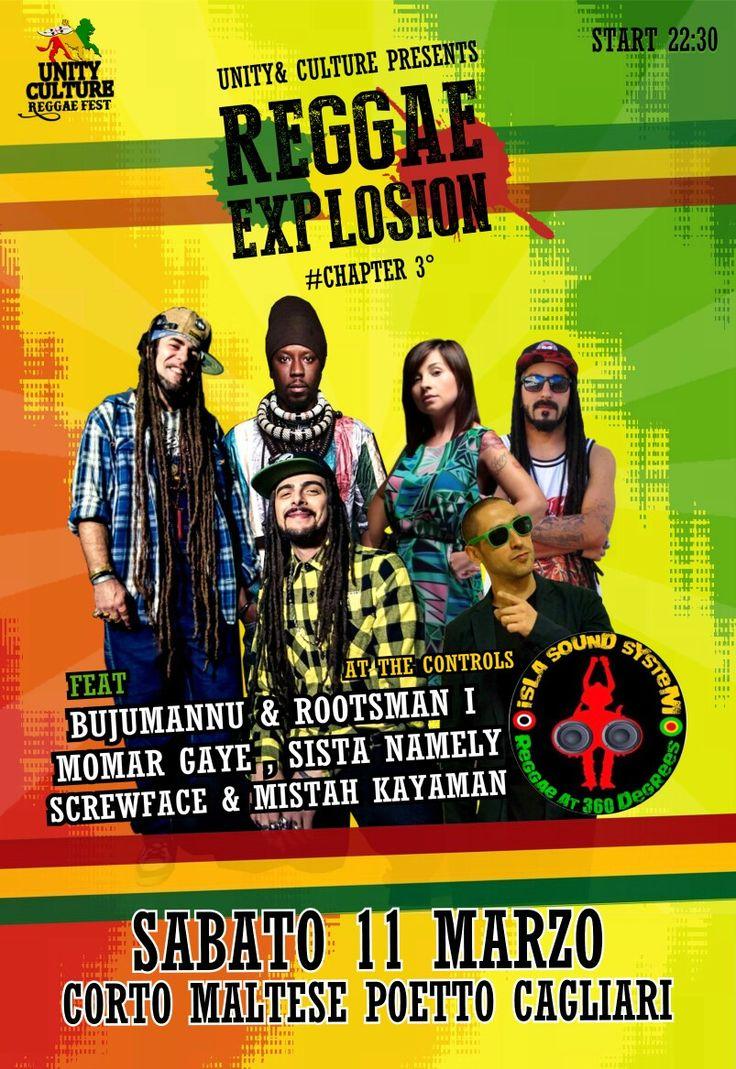

Reggae Explosion festival poster, Cagliari, Italy

While music can neither eliminate racist extremism nor overturn increasingly stark racial and ethnic divisions, particularly when these continue to be stoked from above, it remains undervalued as a tool for promoting social cohesion across cultures. Music is part of our evolutionary DNA and allows us to communicate beyond the linguistic realm and to build social bonds.1 As Schulkin and Raglan assert, “It strengthens social ties and relational connectedness and intersects with social and cultural boundaries.”2 Music is thus a powerful medium for intercultural connection, communication, and collaboration, permeating cultural and linguistic borders worldwide through processes of exchange and synthesis. The music of Momar Gaye and his band allows us to see explore some of these qualities in context.

Gaye’s production and dissemination of a Senegalese version of a post-colonial and pan-African form of popular music originating in the Caribbean, and now emanating from the Mediterranean island of Sardinia, underscores music’s complex transcultural and transnational dimension. Sung in a mixture of Wolof, French, English, and Jamaican Patois, Gaye’s work reflects—both musically and lyrically—the layering of indigenous, (post)colonial, and diasporic elements, and amplifies the circularity of music’s global flows. He continues a tradition of African musicians that have been inspired by Jamaican icons such as Bob Marley and Peter Tosh to adopt this syncretic diasporic style as a means of expressing anti-colonial, anti-racist, and intercultural solidarities.3 As a global genre, whose dissemination has been facilitated by commercial and media networks, reggae has been adopted by diverse and often marginalized communities around the world as a means of expression (Manuel). Like all modern popular music from the Caribbean, and much of Africa, reggae’s creation and diffusion is bound up in the dynamic dimensions of global cultural flows that Appadurai described as “ethnoscapes,” “mediascapes,” “technoscapes,” “financescapes,” and “ideoscapes.”4 In fact, due to music’s fluid quality one might also accurately speak of “soundscapes” to explain the way that music leads to transnational connections and alliances through flows of meaning.5

Screenshot of video for the song 'Satati' by Momar Gaye and band Zaman, shot in Sardinia

Two specific examples from Gaye and Zaman’s oeuvre convey the way in which their brand of Afro-reggae fusion is immersed in such flows and creates new connections and alliances. Shot in Cagliari, Sardinia, the videoclip for the title track of their 2010 album, Santati (S’ard Music), establishes a symbolic connection between Senegal and Sardinia. Natural landscapes allude to commonalities between these two geographies, while images of the Senegalese and Sardinian members of the band interacting and jamming together reinforce the clip’s underlying themes of integration and harmony. In turn, the lively Afro-reggae reggae rhythm and the Wolof lyrics, which are sung and toasted in a Jamaican dancehall style, fashion a soundscape highlighting the continuities and multidirectional periphery-to-periphery cultural currents between Africa and the Caribbean.

Reflecting the way in which music is embedded in the global flows of people, technology and media, Zaman’s most successful song, “Zamina (Waka Waka),” from the same album, covers a transnational makossa hit from the Cameroonian band, Golden Sounds (or Zangawela as they were later known). First recorded in 1986, the song “Zamina mina (Zangaléwa)” resonated throughout Africa and the Caribbean. It became a favorite amongst the Afro-Colombian costeño communities of Colombia in Cartagena and Baranquilla, and the catchy chorus was integrated into the 1988 cover of Georgie Dann’s dubiously titled “El negro no puede” (RCA, 1987) by the renowned all-female merengue group from the Dominican Republic, Las Chicas del Can.6 In turn, further songs incorporating the chorus emerged in diverse locations throughout the globe (France, the Netherlands, Rwanda, Suriname, Liberia, and Senegal) even though it was sung in Douala and remained incomprehensible within these new contexts. The chorus’s diffusion thus demonstrates rhythm and melody’s capacity to communicate across cultural and linguistic borders.7

Like all modern popular music from the Caribbean, and much of Africa, reggae’s creation and diffusion is bound up in the dynamic dimensions of global cultural flows...

However, with close to 2 billion views on YouTube, the most successful, renowned, and controversial take on the original has been Shakira’s 2010 megahit for Sony and FIFA, “Waka Waka (This Time for Africa),” featuring Freshly Ground. Halbert contends that despite being the anthem for an event which promotes narratives of nationalism, the song also “unintentionally demonstrates the complexities of culture, identity, nationalism, and the power of musical diaspora” and “aligns with the hybridity of our expressive cultures against both nationalist impulses and state control.”8 The song is thus “emblematic of how music can disrupt national borders and demonstrates how cultural expressions evolve through direct contact and inspiration.”9

Screenshot of video for the singer Shakira's song 'Waka Waka (This Time For Africa)'

Despite the center-periphery power imbalances inherent in Shakira and Sony’s appropriation of the original, it is likely that Shakira, who was born and raised in the Caribbean coastal city of Baranquilla (Colombia), first heard the original as a child. The song was popular amongst local DJs from the Afro-Colombian champeta scene, which evolved within the ‘non-official’ networks of the picós in Cartagena and Baranquilla. During the 1970s, these bass-heavy technicolor sound systems10 began to play recordings of what was generically referred to by the locals as música africana. These records were likely introduced by sailors and comprised diverse yet interconnected Caribbean and African genres, such as makossa, soukous, highlife, and mbaqanga from Africa, and compass, soca, and reggae from the Caribbean.11 As Hernandez explains, this strong identification with música africana by coastal Afro-Colombians demonstrated the articulation of an imagined community which was defined by the “region’s common African musical roots” rather than a “shared geographical space or shared language.”12 It appears, therefore, that Shakira’s familiarity with and connection to the song was the product of Afrocentric diasporic networks and affinities—within Colombia and the Caribbean—in combination with the song’s broad melodic and rhythmic appeal. All these factors made it a logical choice by Shakira for the anthem to accompany the first truly global African sporting event.

These records were likely introduced by sailors and comprised diverse yet interconnected Caribbean and African genres, such as makossa, soukous, highlife, and mbaqanga from Africa, and compass, soca, and reggae from the Caribbean.

Back in Italy, Zaman’s lively cover, predominantly sung in Wolof, was released in the same year as Shakira’s and followed Senegalese hip hop-reggae pioneer Didier Awadi’s 2007 version, “Zamouna” (Studio Sankara). Like Shakira, Gaye would have known the song for some time and been aware of its intercultural appeal and capacity to complement Zaman’s integration focused music project. Reflecting this, the videoclip presents images of Gaye and the multiethnic band as they inspire a roomful of joyous Sardinians to move and clap their hands to African percussion and rhythms.13 Video from 2010 of Zaman performing the song before a large and highly participatory audience in Cagliari further documents the song’s power to communicate and foster social bonds across cultural and linguistic barriers. The general sense of solidarity evoked during the performance is made explicit when Gaye addresses the crowd directly in Italian to thank them for making him and his band feel “at home” for the past 10 years, providing evidence of the way in which music “creates and articulates the very idea of community.”14

The above snapshot of music’s transnational and transcultural appeal suggests that it is an effective tool in promoting new and reciprocal solidarities, exchanges, and connections. Greater funding from government and charitable and philanthropic sources for projects and initiatives that bring together host and newly arrived communities through music, and which support intercultural ambassadors such as Momar Gaye and Zaman in their work, would greatly benefit such exchanges and connections.

1. See Mithen, S. J. (2005). The Singing Neanderthals: The Origins of Music, Language, Mind, and Body. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

2. Schulkin, J. & Raglan, G. B. (2014). The evolution of music and human social capability. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 8, pp. 1-13.

3. See Nigeria’s Sonny Okosun, Côte d'Ivoire’s Alpha Blondy and South Africa’s Lucky Dube

4. Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

5. Pérez, J. (2006). The Soundscapes of Resistance: Notes on the Postmodern Condition of Spanish Pop Music. Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies, 7 (1), pp. 75-91.

6. El rincon del viejo Use. (2017, April 27). EL NEGRO NO PUEDE con letra LAS CHICAS DEL CAN [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/AZA7ht0qYec.

7. Around the World... Waka Waka Hey Hey! (2012). Retrieved from http://blog.wfmu.org/freeform/2010/03/waka-waka-hey-hey.html.

8. Halbert, D. (2014) The State of Copyright: The Complex Relationships of Cultural Creation in a Globalized World. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, p. 118.

9. Ibid, p.119.

10. These self-constructed sound systems parallel those that engendered Jamaican popular music forms, ska, rocksteady, reggae, and dancehall.

11. Pacini Hernandez, D. (1996). Sound Systems, World Beat and Diasporan Identity in Cartagena, Colombia. Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies, 5 (3), pp. 429-466.

12. Ibid.

13. ZamanOfficial. (2010, July 8). Momar Gaye & Zaman - Zamina (Waka Waka) - Official Video [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/248z_2-324g.

14. Frith, S. (1992). The Cultural Study of Popular Music. In L. Grossberg, C. Nelson & P. Treichler, P. (Eds.), Cultural Studies (pp. 174-186). New York: Routledge.