Living with Upheaval: LGBTQ+ Asylum Seekers Performance, Healing, and Political Praxis

archive

Crossing Pride Collective hosting LGBTQ Refugee Pride Reception during Stockholm Pride, 2023.

Living with Upheaval: LGBTQ+ Asylum Seekers Performance, Healing, and Political Praxis

Queer Migration Studies have disproportionately focused on how the governmentality of asylum and refugee status remains entangled with sexuality and gender identity or has engaged with recent mobilizations within LGBTQ+ immigrant communities against coercive border control regimes (Aizura 2012 & 2018; Cantú et al, 2020; Camminga 2017 and 2019; Luibhéid 2002; Chávez 2013 & 2021; DasGupta 2011 & 2019). These approaches have not often enough included the voices of LGBTQ+ immigrants and refugees, and therefore have missed the opportunity for a fuller account of the affective and embodied experiences of migration and asylum.

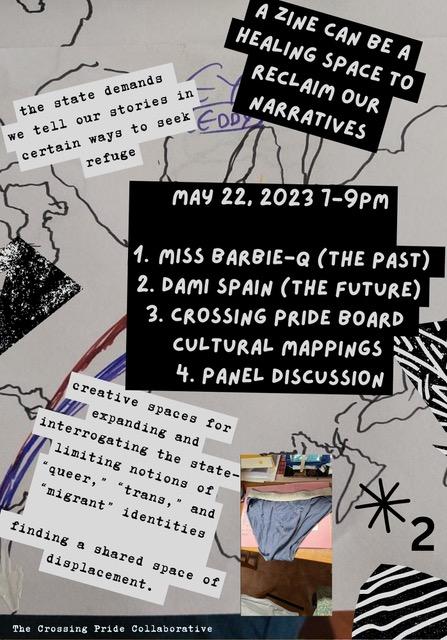

Over the course of the last three years Crossing Pride built a multi-campus (University of California, Santa Barbara and University of California, Irvine), multi-disciplinary project (drawing on Feminist Studies, Feminist Geography, Public Policy, Theater and Performance Studies, Visual Culture Activism, Militarism, Migration) in collaboration with migrants, refugees, as well as asylum seekers who have resettled from Egypt, Serbia, Syria, Kenya, Palestine, Russia, and Pakistan.1 We held collaborative storytelling, zine-making, and healing workshops aimed at creating a set of shareable tools for creating and sustaining refugee-led transnational support and healing networks (Arani, Alexia, and Anna Renée Winget, 2022). By spring 2024, the Crossing Pride collaborative had developed a full-length story-telling performance, My Story Doesn’t End.

![Cover of the zine program for the performance of My Story Doesn’t End, 2024; Image 2: Page 2 credits from zine program for the performance of My Story Doesn’t End, 2024].](/sites/default/files/styles/container_image/public/images/Untitled%20design-7.jpg?h=f51c32db&itok=eOjihH8U)

Image 1: Cover of the zine program for the performance of My Story Doesn’t End, 2024; Image 2: Page 2 credits from zine program for the performance of My Story Doesn’t End, 2024].

Staged readings were held at UCI and at Highways Performance Space in Los Angeles in the Spring of 2024. Our community board members and migrant colleagues brought diverse sets of expertise in transnational trans rights, advocacy for women and girls, trans migration rights, and, importantly, their “flesh and blood experiences,” life experiences that Cherríe Moraga calls, “theory in the flesh,” (Bridge 23) to the development of this project. Taking up Moraga’s theory in the flesh calls for returning to the lived experiences of transnational migration, displacement, and attempts at community-building led by queer refugees. As researchers, we remain committed to utilizing humanities research methods such as story-telling, zine-making, and drawing maps that center spaces and places central to queer refugee subjects. In doing so, the project aimed at producing creative technologies for registering the voices of queer refugees. The narratives developed by the queer refugees through zine and map-making workshops and peer-support discussions provided participants an opportunity to develop a grip over their traumatic displacements, rather than centering what law or civil society requires from the queer refugees in order to bestow upon them refugee status (Gottvall, Maria, et al; 2024).

In this article, we center excerpts from a longer joint interview between Dr. Anna Winget, one of the United States collaborators on the "Crossing Pride Project" and Ronah Ainembabazi, a Crossing Pride Community Advisory Board member in Sweden in order to reflect upon some of the key insights gained by the Crossing Pride work. We consider what is possible if Queer Migration Studies is approached by foregrounding theory in the flesh and therefore the embodied experiences and expertise shared through community-centric creative collaboration. One of our funding sources, the University of California Humanities Research Institute, funded us under their COVID pandemic-inspired theme of “living through upheaval.” We argued that upheaval is not just something that is lived through for LGBTQ+ refugees and migrants, but rather upheaval is a condition of violence and disruption that is continually in process. In the excerpts that follow Winget and Ainembabazi consider these and other questions.

INTERVIEW

Ronah Ainembabazi

I am a social worker and founder of Mama Girls Foundation, Uganda. I have just been here in Sweden the last few years.

Anna Winget

The original goals of the Crossing Pride collaborative project were about creating spaces for community-led healing, storytelling, and archiving and to raise awareness around conditions in order to inform policymakers on needed changes. Ronah, what kind of questions and experiences brought you to this work?

RA

I've been so much in the community and of the LGBTQ community, but also I had the experience of growing up as a lesbian in my country, Uganda. I have seen many of the challenges that women and girls face growing up as a women and girls—and I wouldn’t want the young girl, the young me, to face that, so I was motivated to change conditions for others. This is what brings me to Crossing Pride: finding a place to give voice for the voiceless. What brings you to this work?

AW

After completing my degree in the Joint Ph.D. Program in Theater from UC Irvine and UC San Diego, I moved to Sweden from the U.S. and started volunteering with RFSL’s Newcomers Project, a group for LGBTQI people and refugees who are newly arrived in Sweden. As a white American with U.S. citizenship, I don’t have the lived experience of going through the asylum process, but I began to hear from Newcomers themes of feeling invisibilized, unheard, and misunderstood by the Swedish society. I was thinking about how most refugee narratives, whether LGBTQ+ or not, when they do get attention, are narratives about danger or safety–either about oppressive conditions or a savior narrative such as ‘Sweden saved me.’ I'm thinking of documentary films like Flee (Dir. Jonas Poher Rasmussen, Denmark, France, Norway, and Sweden, 2021) which combines animation and archival footage to tell the story of a gay Afghan refugee that migrated to Denmark. Flee definitely has that arc of oppression, but that’s just not the narrative arc that I’ve heard most often in the many, many, many firsthand

stories of LGBTQ+ refugees that emerged in our performance and healing work with Newcomers. What was striking in these narratives are the accounts of how the violence continues, but in different and in new forms. Violence can come in the form of racism and the existing xenophobia in destination countries, or the violence of lack of access to basic needs. And, I think significantly for our project, the demand is there to provide credibility as an asylum seeker through a specific (state-sanctioned) narrative of who you are, including recounting the violence that you’ve endured in specific ways. Each of these experiences can be very traumatic and, collectively, they represent ongoing traumas (the living with rather than through upheaval [the original language of the UCHRI initiative that funded Crossing Pride]. In addition to the PTSD from past traumas, which led to the need to seek asylum, newcomers experience ongoing and new traumas. We realized there was both a more complex narrative that needed to be told and a need to tell one’s story outside of these state-based demands for narratives specifically framed for asylum legal processes.

RA

I did that compulsory storytelling. Moving to a new country is not easy. And then that is compounded by being an asylum seeker. Here in Sweden, apart from the questions asked of you during the immigration process, we didn’t have places where you can go and express yourself and talk about the trauma, and talk about the experiences, the life experiences we’ve had. We come from different countries, and we are handled differently in the asylum process. We also had to learn the language to be able to mix in, in a new country, and be able to cope up with everything. Sometimes it’s not easy. Apart from giving you that freedom–freedom that you are not certain that you will be killed, well, the rest, you still have to go through. You have to pull yourself up, where sometimes it is not easy because of the torture and the trauma you have come from. This is why the healing sessions we put together for people were important: for them to be able to express themselves, to talk about themselves, not for the state, but for each other as a part of this project of Crossing Pride. By talking and telling stories, we could even refer them to the right people to give them support. It’s totally not easy, but we move on. Mingling in society is not easy: We are each brought up differently, we have different norms and social nodes, different, different languages. It becomes hard when you are leading a person who is torn apart and has been through so much. They might express their anger or new feelings because they have not fully healed.

AW

I think that it is really important that through it all, the pain has somewhere to go. One of our goals has been to provide a space where that pain can be transformed into activism or art,—and just creating a space for being able to show up for each other. Why do you think it has been important to center healing through storytelling and archiving?

RA

One thing I would like people to know is that from reading our stories and engaging the archives of our experiences is that they don’t involve one particular country. These stories show this process all over the many countries where LGBTQ persons experience discrimination and violence. The stories that are being told are not from one country. So instead of delaying processes and delaying asylum processes, let these processes be worked upon, you know, in the earliest way because these people are always in danger. And do not think that deportation is the option. Because you have someone who has been in a country for so many years, for example, maybe seven years, and then you deport them to their countries of origin. For example, I was working with someone who had come to Sweden seeking asylum and they deported this person back to their country after years and immediately this person was dropped at the airport and arrested for two more years. Can you imagine you have come from Sweden, your asylum process has not been granted and then you go back to your own country, and they arrest you for two years. Those are the worst policy ideas that I keep talking about and want to change. This person will never account for the years that they spent in the asylum process, and you'll never account for them.

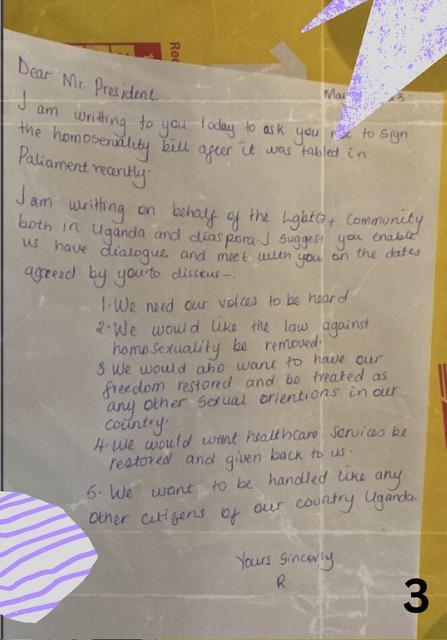

Page 3 from the program zine for the performance of My Story Doesn’t End.

CONCLUSION

After three years of transnational collaboration, we found that the work necessitated a vital re-framing of the ethics of transnational collaboration and university/community engagement. Our experience highlighted the value of working with community members as experts who bring their experiences to our collective in order to name the contradictions that frame queer refugee livability. In her interview, Ronah discusses the story of a person who lost their asylum claim in Sweden, and after seven years was deported to their country origin. They were arrested and remained in prison for two years. This reveals the fault lines of the asylum process in the global North that demands adequate proof of persecution based on gender identity and sexuality. Ronah gestures us toward queer refugee temporality, wherein escape from persecution into a life of freedom remains an impossible fantasy. Rather, the disruption of immobility, detention, and deportation creates injuries that remain forever etched in the queer refugee subject’s psyche. The Crossing Pride Collaborative project became a space where queer refugees could narrate these injuries, the difficulties with re-adjusting to a new country, language, and medical system. The title of the play, “My Story Doesn’t End,” that was collectively developed reflects these insights.

Page 1 of the zine program for the performance of My Story Doesn’t End, 2024.

This title gestures toward the continuing challenges of healing from trauma that is related to displacement and resettlement, the living with upheaval. Further, this play and performance (staged by actors who were trans and queer people of color living and working in Los Angeles and Oakland, CA because of the restriction and limitations of travel for the migrant, refugee, and asylum seekers community members) troubles ideas about healing where queer refugees have resettled. A queer refugee story (in this performance and in lived experience) is not a linear narrative of progression from persecution to freedom, rather these are stories of living with continuous displacement and un-belonging.

The Crossing Pride collaborations received funding from University of California, Humanities Research Institute, 2021-2022 and 2022-2023; Illuminations, the University of California, Irvine Chancellor’s Arts & Culture Initiative, 2021-2022 and 2022-2023; and a Faculty Collaborative Research Grant, University of California, Irvine Humanities Center 2021-2022.

Aizura, Aren Z. “Transnational Transgender Rights and Immigration Law.” Transfeminist Perspectives in and Beyond Transgender and Gender Studies. Philadelphia: Temple UP (2012): 133-50.

Aizura, Aren Z. Mobile Subjects: Transnational Imaginaries of Gender Reassignment. Duke University Press, 2018.

Arani, Alexia, and Anna Renée Winget. “Introduction to Queer Healing and Transformative Justice Special Issue of QED.” QED: A Journal in GLBTQ Worldmaking 9.3 (2022): 1-9.

Camminga, B. Transgender Refugees and the Imagined South Africa: Bodies Over Borders and Borders Over Bodies. Cham: Palgrave MacMillan, 2019.

Camminga, B. “Categories and queues: The Structural Realities of Gender and the South African Asylum System.” Transgender Studies Quarterly 4.1 (2017): 61-77.

Cantú, Lionel, Eithne Luibhéid, and Alexandra Minna Stern. "Well Founded Fear: Political Asylum and the Boundaries of Sexual Identity in the US–Mexico Borderlands." Feminist Theory Reader. Routledge, 2020: 220-227.

Crossing Pride Collaborative, “My Story Doesn’t End,” unpublished script, 2024.

Crossing Pride Collaborative, Zine Program for “My Story Doesn’t End,” 2024.

Chávez, Karma R. Queer Migration Politics: Activist Rhetoric and Coalitional Possibilities. University of Illinois Press, 2013.

Chávez, Karma R. The Borders of AIDS: Race, Quarantine, and Resistance. University of Washington Press, 2021.

DasGupta, Debanuj. “Queering Immigration: Perspectives on Cross-Movement Organizing.” Scholar and Feminist Online 10.1-2 (2011).

DasGupta, Debanuj. “The Politics of Transgender Asylum and Detention.” Human Geography 12.3 (2019): 1-16.

Gottvall, Maria, et al. “Mental Health and Societal Challenges Among Forced Migrants of Diverse Sexual Orientations, Gender Identities and Gender Expressions: Health Professionals’ Descriptions and Interpretations.” Culture, Health & Sexuality (2024): 1-16.

Luibhéid, Eithne. Entry Denied: Controlling Sexuality at the Border. University of Minnesota Press, 2002.

Moraga, Cherríe, and Gloria Anzaldúa, eds. This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. 2d ed. New York: Kitchen Table Women of Color Press, 1983.

Rasmussen, Jonas Poher, dir. Flee. 2021; Denmark, France, Norway, and Sweden.