What Do Cambodia and Hungary Have In Common? Trump!

archive

What Do Cambodia and Hungary Have In Common? Trump!

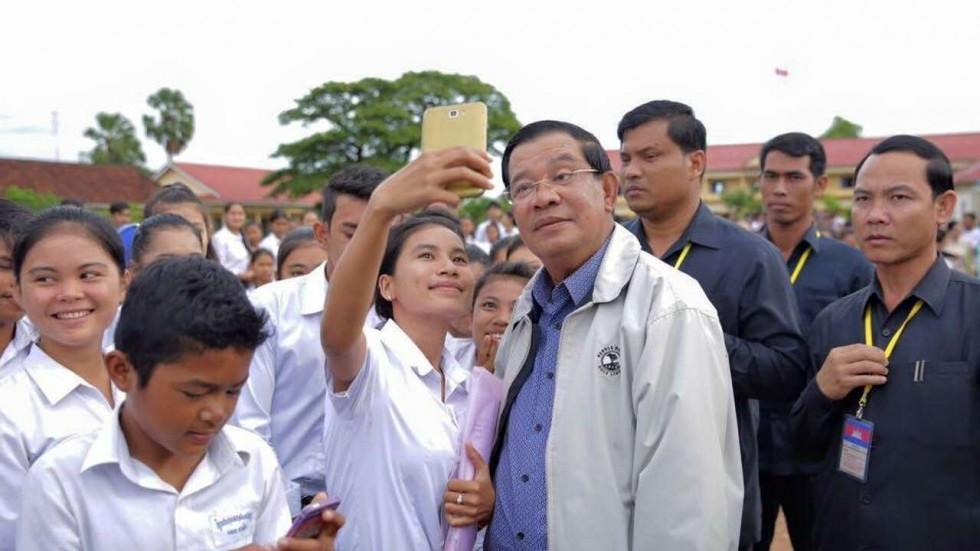

Only two heads of government expressed open support for Donald Trump during the U.S. election campaign when it seemed unlikely that he would win. The two are Hungarian Prime Minister Orbán Viktor and his Cambodian counterpart, Hun Sen. What brings these two men—one who launched his career calling for the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Hungary in 1989 and the other who became prime minister in 1985 when Cambodia was a client state of the Soviet Union—into the same camp?

It is true that both Orbán and Hun Sen have had run-ins with Hillary Clinton, who as secretary of state criticised their human rights records. They could expect no better from her had she won the presidency, so betting on Trump was a pragmatic choice. But there are some deeper-running sympathies that tie the three men together.

The Cambodian and Hungarian leaders are among a growing group of nationalist politicians around the world—including Egypt’s al-Sisi, Turkey’s Erdogan, and the Philippines’ Duterte—who praise the values of discipline and hard work, stress the need for industrial growth, dismiss objections to the curtailing of civil and labour rights, are quick to label opponents as traitors and terrorists, deride “political correctness,” and cultivate macho personas. Internationally, these leaders, along with China and Russia, demand that the U.S. give up its idea of exporting democracy. Orbán also wants the EU to stop what he sees as the imposition of a liberal agenda on citizens of its member states; instead, it should strengthen its borders and defend its core “Judeo-Christian” values from the onslaught of migrants. It is unsurprising that Orbán and Hun Sen, as well as Duterte (who has made friends with China and recently described Obama in expletives) support Trump, who is uninterested in the promotion of human rights abroad and whose views resonate with theirs on several points. Meanwhile, al-Sisi seems likely to become friends with Trump, while Erdogan will have to wait and see whether Trump can live with his brand of Islamism.

It also makes sense that these same politicians are friendly towards China and Russia, which have been happy to second their views and oblige with some economic support. Orbán has come full circle on Russia; he now seeks good relations with President Putin and has been ambivalent about Russian intervention in Ukraine and opposed the sanctions that followed. Hun Sen’s relations with Russia date back to Soviet times and are still cordial.

As for China, Cambodia and Hungary are the PRC’s most committed allies in Southeast Asia and Eastern Europe respectively. Like Hun Sen, Orbán has called China a strategic partner and an “old friend.” Both seek to profit from the Chinese government’s “New Silk Road” and “Maritime Silk Road” initiatives, which aim to support the construction of infrastructure linking China to Europe. China’s move to set up the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank in 2014 and a $40 billion Silk Road Fund are well known. But back in 2012, China announced a credit line of $10bn earmarked for Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), and in 2014 set up another investment fund for the region with capital of $3bn.

It is unsurprising that Orbán and Hun Sen, as well as Duterte... support Trump, who is uninterested in the promotion of human rights abroad and whose views resonate with theirs on several points.

Attracting Chinese and Russian investment has been a way for both governments to reduce their dependence on Western governments. Hun Sen has faced Western criticism for his government’s human rights abuses and its persecution of the opposition. He has also been cited for extorting money from business executives since he returned to power in a 1997 coup. (Only the Hungarian and Chinese delegations called the last, 2013 election free and fair.) Orbán has been having similar trouble since 2010. Hungary’s rapid slide in human rights, press freedom, and transparency rankings has been compounded by its fall from the top to the middle of Eastern European countries in terms of foreign direct investment (FDI) and GDP.

Both leaders have reacted defiantly to criticism and turned to alternative patrons. Both have gone to great lengths to secure China’s goodwill: Hungary banned a demonstration by members of the Falungong religious movement, which is illegal in China, and rounded up Tibetans during the Chinese premier’s visit in 2011. Since the early 2000s Cambodia has been deporting Falungong members and asylum-seeking Uighur separatists back to China.

Orbán’s friendly gestures towards Putin secured Russian financing for the expansion of a nuclear power plant, with conditions that have not been made public. In 2011, Hungary became the first European country to benefit from a Chinese investment and loan “package,” which included buying some of Hungary’s debt. Since then, China has provided a loan for upgrading the Budapest-Belgrade railway, under similarly opaque conditions. The opposition believes both projects are so expensive that they make no economic sense. An “investment immigrant” program mainly targeting Chinese has been criticized as well for generating more expenses than budget income. The largest Chinese investments in the country have been the purchase of Borsodchem, a chemical company, by a state-owned Chinese enterprise, and the setting up of a European regional support and logistics center for telecom giant Huawei. Both purchases were backed by loans from state-owned Chinese banks. Overall, Russia and China have not become serious alternatives to the EU as sources of investment, but they have provided government cronies with handsome profits.

Cold War-era authoritarian leaders were divided along ideological lines. Today, their friendships are non-ideological. They can even transcend the boundaries of alliances such as the EU and NATO. Each leader is free to promote his version of chauvinism as long as it lets the others do the same.

In Cambodia, meanwhile, China has been the top source of investment (both state-backed and not) for some years, ranging across sectors but concentrated in infrastructure, mining, and real estate, including a 360 km² beachfront tourism development with a total projected investment of $3.8 billion. (Russian investment has been on a much smaller scale.)

Cold War-era authoritarian leaders were divided along ideological lines. Today, their friendships are non-ideological. They can even transcend the boundaries of alliances such as the EU and NATO. Each leader is free to promote his version of chauvinism as long as it lets the others do the same. Help me catch my “terrorists” and I’ll help catch yours.

Orbán, for example, has been vehemently opposed to Muslim immigration while cultivating a cordial relationship with Erdogan. President-elect Trump, who is popular in both Russia and China, has the credentials to join this club. Global Times, a popular newspaper in Beijing that is vehemently anti-American, greeted his election with glee. If Trump is to make good on his infrastructure construction promises, he is likely to welcome investment from China, both in infrastructure and more broadly, and try to persuade Congress to relax its scrutiny. This could have benefits for both countries, although the number of jobs might be lower than expected if Chinese companies are allowed to bring their work force. If Trump’s investment projects and his friends are any guide, his presidency will not be opposed to global trade, but will prefer channels that rely on personal understanding with political and business friends over more transparent and regulated arrangements.

Orbán, for one, is already bragging about his invitation to the White House. He says when he called to congratulate Trump and complained that, for the past eight years, the U.S. administration had treated him like a black sheep, the president-elect laughed and said, “Me, too.”