The Role of Universities in Cultural Heritage Protection

archive

The Role of Universities in Cultural Heritage Protection

The global tourism industry has generated intense interest in and pressure on major archaeological and historic sites around the world. In addition, ethnic, religious, political and environmental disputes have arisen around some of these places. The field of cultural heritage management addresses these and other issues. This brief paper discusses two important cultural heritage management and research projects conducted by faculty affiliates of the Collaborative for Cultural Heritage and Museum Practices (CHAMP) at the University of Illinois. Their work highlights the role of universities in cultural heritage protection.

In 1992 Hindu nationalists demolished a 16th-century mosque in Ayodhya, Gujarat state, India, that had been built atop the site considered to be the birthplace of the Hindu god, Rama. Deadly riots between Muslims and Hindus ensued. Ten years later, 57 Hindu train passengers were killed by Indian Muslims as they returned from Ayodhya, an attack prompted by Hindu preparations to build a new shrine in Ayodhya. Hindus immediately retaliated for the train attack and soon Gujarat was engulfed by bloodshed and widespread destruction of homes, shops and religious sites. Seen alongside UNESCO’s mantra that cultural heritage belongs to all humankind and must be respected, protected, and embraced, the violence in Gujarat challenged the idealistic notion of universal cultural heritage.

This was the context in which four professors from the Department of Landscape Architecture, in association with Indian partners from the Baroda Trust, undertook a heritage conservation project at Champaner-Pavagadh, a Hindu-Muslim contested site in Gujarat. The landscape intervention plan formulated by my colleagues Amita Sinha, James Wescoat, Gary Kesler and D. Fairchild Ruggles aimed to connect the residential population of Champaner city with the sacred hill of Pavagadh and in so doing mitigate the explosive potential of this pilgrimage site.

They paid equal attention to the existing medieval mosque and to the Hindu pilgrimage summit so as to conserve culturally hybrid sites. Their design enhanced historical paths, water features and human settlements (Sinha 2004; Sinha et al. 2003) and “harmonize[d] contemporary tourist and pilgrim interests; illuminate[d] the manifold historical contribution of Sultanate, Rajput, Jain and tribal groups; and thereby deepen[ed] contemporary appreciation of the pluralistic cultural legacy at Champaner-Pavagadh” (Wescoat 2007). Their plan also encompassed local community development by means of shop houses and communal spaces (Sinha et al. 2005).

This was the context in which four professors from the Department of Landscape Architecture, in association with Indian partners from the Baroda Trust, undertook a heritage conservation project at Champaner-Pavagadh, a Hindu-Muslim contested site in Gujarat. The landscape intervention plan formulated by my colleagues Amita Sinha, James Wescoat, Gary Kesler and D. Fairchild Ruggles aimed to connect the residential population of Champaner city with the sacred hill of Pavagadh and in so doing mitigate the explosive potential of this pilgrimage site. They paid equal attention to the existing medieval mosque and to the Hindu pilgrimage summit so as to conserve culturally hybrid sites. Their design enhanced historical paths, water features and human settlements (Sinha 2004; Sinha et al. 2003) and “harmonize[d] contemporary tourist and pilgrim interests; illuminate[d] the manifold historical contribution of Sultanate, Rajput, Jain and tribal groups; and thereby deepen[ed] contemporary appreciation of the pluralistic cultural legacy at Champaner-Pavagadh” (Wescoat 2007). Their plan also encompassed local community development by means of shop houses and communal spaces (Sinha et al. 2005).

Their achievement of multiple goals was demonstrated by the fact that while Gujarat burned, Champaner-Pavagadh experienced far less physical destruction. Only two years later the Illinois team helped India gain World Heritage Site status for Champaner-Pavagadh as a testament to its “perfect blend of Hindu-Moslem architecture” and its continuous Hindu pilgrimage landscape.

My colleagues are emphatic that their conservation/protection plan succeeded because it was not premised on the sacred hill summit alone.

Rather, they approached Champaner-Pavagadh as a complex environment with integrated social, economic, political, religious, and natural features. Also, they were able to make a long-term commitment to stewardship of the site, eschewed a narrow focus on building preservation, and brought to the project an academically deep understanding of the Mughal Empire, Hindu sacred landscapes, Indian politics and history, and local traditions.

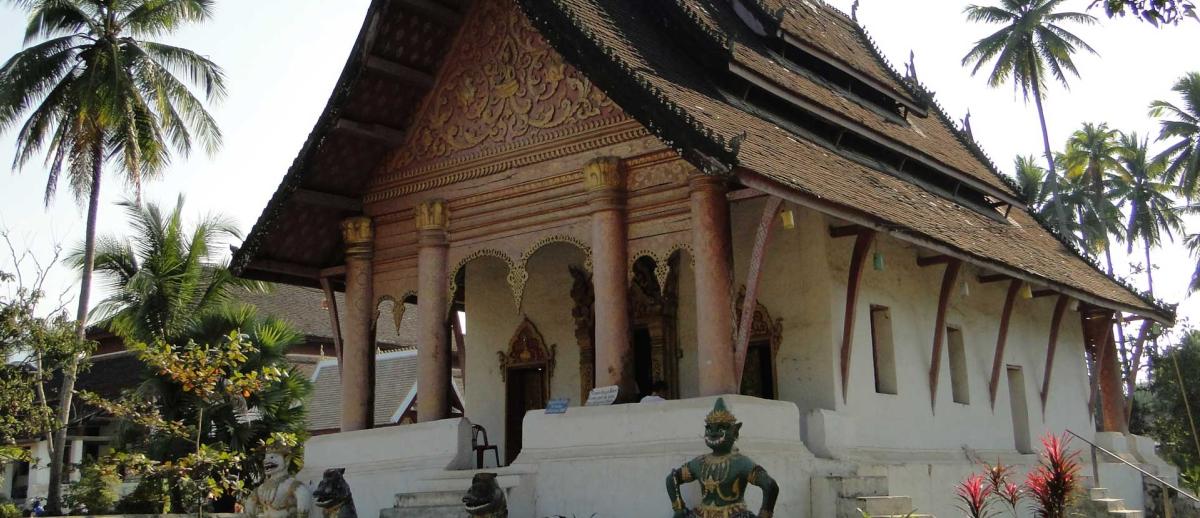

Luang Prabang, Laos, offers a different scenario of heritage protection. Luang Prabang was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1995, in part as an emergency measure taken by UNESCO against its imminent destruction by a major Chinese highway that would soon run through the middle of the beautiful ancient city en route to Vientiane. The highway was diverted to comply with UNESCO requirements and Luang Prabang is currently praised as “an outstanding example of the fusion of traditional architecture and Lao urban structures with those built by the European colonial authorities in the 19th and 20th centuries. Its unique … townscape illustrates a key stage in the blending of these two distinct cultural traditions” (http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/479).

the World Heritage inscription and its resulting architectural preservation and urban redevelopment “have refined and redefined what heritage is in Luang Prabang, freezing the physical environment of the city as an imagined space/time.”

Dearborn and Stallmeyer’s analysis of the Maison du Patrimoine’s management plan reveals a singular representation of the city’s cultural heritage that erases “particular physical and socio-cultural pasts that are seen as unpalatable for tourists, are incongruent with contemporary development, or do not serve the political needs of the current Lao PDR government.” Luang Prabang today dutifully attends the needs of a global tourism industry but, as Dearborn and Stallmeyer observe, “the erasures necessitated by this process leave little room for the performance of locally embedded everyday activities or multiple readings of heritage.” Moreover, the World Heritage inscription and its resulting architectural preservation and urban redevelopment “have refined and redefined what heritage is in Luang Prabang, freezing the physical environment of the city as an imagined space/time.” The result is a physical environment increasingly transformed into a touristic display, rendering invisible Luang Prabang’s embedded, intangible heritage.

University scholar-practitioners are especially qualified to conduct cultural heritage projects. Our academic training makes us aware of the multiple conflicting institutions and interests that surround all cultural heritage initiatives. We argue that to undertake site protection with unquestioning adherence to adages of universal cultural heritage, or uncritical belief in the inherent value of heritage for the construction of identity, or to automatically advocate economic development through cultural heritage tourism, is to invite failure on the ground. Because we are not a profit-driven business, are reasonably unconstrained by time (at least until our grants run out), and have a university base, we do not operate in the service of influential interest groups and we are sensitive to local stakeholders whose voices typically receive inadequate attention from those in power.

Hopefully, as more universities develop programs in cultural heritage, like CHAMP’s, and their graduates move into the field of heritage management we should see greater success in the democratic management and benign sustainability of all kinds of cultural heritage sites and intangible traditions.

Dearborn, Lynne and John Stallmeyer

2010. Inconvenient Heritage: Erasure and Global Tourism in Luang Prabang. Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek, CA.

Logan, William S.

2007. Closing Pandora’s Box: Human Rights Conundrums in Cultural Heritage Protection. In Cultural Heritage and Human Rights, edited by Helaine Silverman and D. Fairchild Ruggles, pp. 33-52. Springer, New York.

Ruggles, D. Fairchild and Helaine Silverman (editors)

2009. Intangible Heritage Embodied. Springer, New York.

Silverman, Helaine (editor)

2010. Contested Cultural Heritage. Religion, National, Erasure and Exclusion in a Global World. Springer, New York.

Silverman, Helaine and D. Fairchild Ruggles (editors)

2007. Cultural Heritage and Human Rights. Spinger, New York.

Sinha, Amita

2004. Champaner-Pavagadh Archaeological Park: A Design Approach. International Journal of Heritage Studies 10(2):117-128.

Sinha, Amita, James L. Wescoat, Jr., Gary Kesler, and D. Fairchild Ruggles

2003. Champaner-Pavagadh Cultural Sanctuary. Gujarat, India. Design proposal and report (48 pp.) submitted to Heritage Trust, Baroda, India. Department of Landscape Architecture, University of Illinois at Urbana, Champaign.

Wescoat, James L., Jr.

2007. The Indo-Islamic Garden: Conflict, Conservation, and Conciliation in Gujarat, India. In Cultural Heritage and Human Rights, edited by Helaine Silverman and D. Fairchild Ruggles, pp. 53-77. Springer, New York.