Politics of Crisis

archive

Politics of Crisis

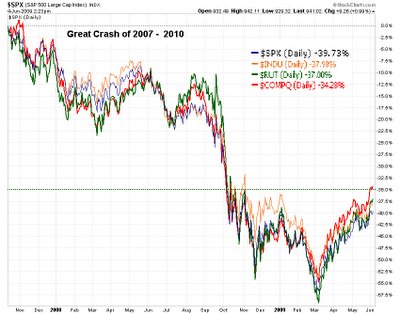

There is broad agreement that the 2008 crisis was caused by financial speculation, enabled by deregulation, in short by ‘permissive capitalism’. After crisis then, we would expect that the Keynesian party of regulation and government intervention should win. Instead, in the US the political winners have been the GOP and the Tea party, and in the UK, the Tories. How do we explain this perplexing phenomenon?

The usual account is the electoral pendulum swing going against incumbents (which implies its swinging back again next time). Also often mentioned is the role of media promoting free market policies. Besides, the incumbents, Democrats in the US and Labor in the UK, have been a party to deregulation and to bailouts of the financial sector without strings attached.

Rather, the general climate is one in which deficits trump regulation deficit hawks rule on both sides of the Atlantic. Regulations of the banking sector, the Frank-Dodd bill in the US and the Vickers Report in the UK, have been thin and meager. The bank reforms in the US have produced even bigger banks. Not only has this not solved the problem of too big to fail but it has created an even larger problem, too big to save. In effect, regulation has morphed into consolidation.

In both countries regulation has been crowded out by the deficit and budget deliberations, which is odd because the deficit didn’t cause the crisis. In fact, for all the talk about the deficit there is little discussion of how it has come about. Nor have there been prosecutions or indictments of bankers—quite unlike after the American Savings and Loan scandal in the early 1980s. Also strangely missing is a public outpouring of moral outrage—tens of thousands marching in the streets furious about financial crisis and government indulgence, crisis-prone behavior on a scale comparable to the Iraq war and the BP Gulf oil disaster. Remuneration of CEOs and bankers is largely back to where it was before crisis, with some cosmetic changes.

The common shortcut explanation for these trends is ‘neoliberalism’. However, ‘neoliberalism’ doesn’t account for the actual variety of ideas nor does it explain why neoliberalism is accepted. To account for this perplexing situation I offer two main hypotheses: intellectual deficit and power deficit. According to the first hypothesis, the key problem is the lack of alternative ideas. At first sight the notion of an intellectual deficit is patently untrue. In the major US and UK newspapers during recent years there has been a steady stream of articles and comments by noted economists making the case for continued stimulus, rather than austerity, and for stronger regulation—such as Paul Krugman, Joseph Stiglitz, Amartya Sen, Robert Reich, Martin Wolf, John Kay, and many others. Yet, the argument can’t be entirely dismissed. Part of the problem is what John Kay calls ‘confirmation bias’: ‘the lesson most people have learnt [from the crash] is that they were right all along.’ So yes there were alternative ideas, but their resonance was not strong enough to sway the prevailing pro-market ideology in mainstream media and public discourse. A mere crash does not undo thirty years of free market socialization since Thatcher and Reagan. On the pages of the Wall Street Journal free market economists have continued their zeal even after the crash. Besides, ideas without organizational momentum carrying them fall short of ideologies.

there were alternative ideas, but their resonance was not strong enough to sway the prevailing pro-market ideology... A mere crash does not undo thirty years of free market socialization since Thatcher and Reagan.

Thus we turn to the second hypothesis, power deficit. That is, there are alternative ideas but the political and public momentum backing them isn’t strong enough and the ideas fall on deaf ears. First, in the US, the political economy of labor, the coalition of Democrats and trade unions, anchored in the industrial Northeast and Midwest, has been steadily eroded by thirty years of deindustrialization. Gone from the public sphere are the Keynesian principles of full employment and deficit spending, viewing trade unions as partners in growth, and Fordist principles of labor productivity and wage growth moving in tandem—not because the ideas have vanished but because the power bloc backing them, in Congress and on main street, has crumbled.

In its stead has come the political economy of services: in finance, insurance, real estate (FIRE), health care, software (Silicon Valley), the cultural industries (Hollywood), retail, education, and the government social sector. The service sector is disparate, ideologically dispersed, unorganized, and many are beneficiaries of deregulation. Wall Street and Silicon Valley are progressive factions of capital that are part of the power base of the Obama administration, that is, progressive in a technological sense. Their main ideological umbrella, if any, is innovation, a techno fix that eschews difficult political and economic questions.

In its stead has come the political economy of services: in finance, insurance, real estate (FIRE), health care, software (Silicon Valley), the cultural industries (Hollywood), retail, education, and the government social sector. The service sector is disparate, ideologically dispersed, unorganized, and many are beneficiaries of deregulation. Wall Street and Silicon Valley are progressive factions of capital that are part of the power base of the Obama administration, that is, progressive in a technological sense. Their main ideological umbrella, if any, is innovation, a techno fix that eschews difficult political and economic questions.

The power shift from manufacturing to services is a general feature of postindustrial society, but there are degrees of postindustrialism. In northwest Europe and Japan offshoring and outsourcing to low-wage countries have generally been balanced by inward investment in technologies and factories, while in the US and UK deindustrialization has been far more drastic.

In the US what industry remains (besides the defense industries) or new industry develops is mostly in the South. Dixie capitalism has gradually taken over from Frost Belt capitalism. Starting in the seventies when industries moved from the northeast they went south. Dixie capitalism and Dixie politics trump Frost Belt capitalism. The Republican Party and the Tea Party reflect different shades of the ethos of the South—low taxes, low services, low wages, no unions. The new Republican governors in Wisconsin, Ohio and Indiana represent the politics of extreme capitalism, feeding on resentment: if private sector workers have meager benefits and no collective bargaining, then public sector workers should not have them either. It is a politics of bringing everyone down to the Dixie level. In America this is what decline looks like. Hence the issue is not simply ideology but what Galbraith called countervailing power.

The problem is not financialization per se but the combination of financialization and deregulation, the problem of the ‘sleeping watchdog’.

Financialization emerged first as an antidote to deindustrialization, masked its effects and enabled the boom of the ‘roaring nineties,’ but has increasingly become a major destabilizing factor, culminating in the crash of 2008. The problem is not financialization per se but the combination of financialization and deregulation, the problem of the ‘sleeping watchdog’. Moreover, low taxes resonate with the market society ethos of possessive individualism. In the US, under the sign of low taxes, liberty trumps equality. In the UK, the Tories call on the Big Society—which is reminiscent of the elder Bush in the US calling on a ‘thousand points of light’ and Bush junior relying on faith-based organizations—suggesting that voluntarism should take over state welfare functions. The paradox is that it is a call to a society in which, given the retreat of the state, market forces have been unleashed, and the call to service therefore falls on deaf ears. A society governed by consumerism and market values is to respond to a call to social values.

What future trends and options do these conditions portend? Given that major trends are of a structural nature—the growth of postindustrialism, services, financialization—major changes in the next ten to fifteen years are not in the cards. The US and UK will likely undergo gradual decline, mitigated to the degree that they play their cards well. Both rely too much on narrow sectors, especially finance, and anti-government ideology undercuts their capacity for self-correction. Northwest Europe is undergoing milder versions of these trends because industry, regulation and social contracts are stronger and free market ideology has less support. The problem of financialization, its size and lack of regulation, however, is a common factor but on a smaller scale than in US and UK. Portugal, Ireland, Greece and Spain face different problems, generally GDP growth outstripping productivity growth, weak regulation, and growth borrowed from external financing.

Editor's Note: To read the full article, please visit www.jannederveenpieterse.com and look at the “Politics of Crisis” PDF.