International Journalism Meets Critical Global Studies

archive

Source: Global Reporting Center

International Journalism Meets Critical Global Studies

Proponents of critical global studies argue that scholars need to “rethink our dominant forms of knowledge production and promote engagement with critical voices and plural epistemologies that typically are not represented in western scholarship” (Darian-Smith 2015, 6). At its heart, this critical approach should be concerned with pursuing global justice (Appelbaum and Robinson 2005), and—more specifically—illuminating global inequalities (Lim 2017).

One aspect of globalization that could benefit from this effort is international journalism—a media profession and practice that explicitly seeks to tell the world’s “true” stories to increasingly global audiences. While there is already long tradition of research on international news in the fields of journalism and mass communication studies (Thussu and Freedman 2003; Paterson and Sreberny 2004; Williams 2011), global studies scholars have much to offer this conversation by highlighting the impoverished ways in which international news organizations sometimes represent cultural difference; such an approach could also expose the shocking inequalities that plague the profession of international news reporting itself.

Behind the stand-up correspondent on television or online, and behind the byline of the major print news organizations, resides a phalanx of “local” news “fixers” comprised of knowledgeable, enterprising individuals who mediate between the worldwide news organizations and the exigencies of local contexts that are charged with speaking to global issues and concerns. As my own recent research on fixers reveals, these media employees are much more than translators or guides hired by foreign correspondents in the field (Palmer 2019). Fixers help journalists secure compelling interviews with people who otherwise might not speak with them. They also help journalists navigate through unfamiliar geographical and cultural terrain, and they help them decide what the “story” actually is (Palmer 2019).

Despite the fact that many foreign correspondents could not function in the field without their fixers—particularly in the age of parachute journalism, where correspondents drop in for only a couple days before moving on to an entirely different region of the world—news fixers comprise an “underground economy” of the international journalism industry (Palmer 2019). They are significantly undervalued and underprotected, and they are often erased from the stories they help to produce.

Multiple Cultural Perspectives

By its very nature, the work of news “fixing” requires that fixers grapple with a variety of cultural perspectives. The ultimate cultural mediators, fixers have to negotiate with competing economic, social, and political agendas. On one level, they help journalists tell stories that will appeal to audiences far away, many of them disinterested or even skeptical observers. For instance, Yizhou Xu, a former fixer and news assistant working with CBS in Beijing, notes that “Americans have a really distinct lens [for] looking at China.” Because of this, Xu says, he had to help a CBS journalists look at China through that “distinct” lens regardless of how myopic he thought it was. “For CBS, pretty much all they care about is how the economy is doing in China, how that affects American companies and manufacturing. That’s one of the biggest ones,” says Xu. “And then the other one is political issues. Rarely do they cover social and cultural issues, unfortunately.”

In this sense, fixers have to be aware of cultural perspectives that might differ from those of the people who live and work in the regions their clients visit. Yet, on the other hand, fixers must also appease a variety of people in the field, some of whom may not take kindly to the foreign journalists’ presence in their part of the world. For example, news fixers often smooth things over when foreign correspondents upset local authorities. They also help visiting journalists convince potential sources to provide an interview to someone they simply might not trust. The very task of news “fixing” exists partially because, at the hyperlocal level, the practice of international reporting is often met with staunch resistance.

By virtue of this cultural mediation, fixers uniquely exemplify the presence of the global in the local and the local in the global. Their labor reminds us of the “stickiness” of cultural difference—which, in this particular case, raises challenges for news organizations that like to think of themselves as seamlessly “global” in scope—while also “reflect[ing] the materiality of globalization that it is already a part of our everyday life irrespective of our wishes and moral demands” (Lim 2017).

The very task of news “fixing” exists partially because, at the hyperlocal level, the practice of international reporting is often met with staunch resistance.

But alongside their negotiation of competing cultural perspectives in the process of doing their liminal work, news fixers also have their own unique cultural perspectives on the profession and practice of international news reporting. These perspectives are of great relevance to critical global studies, which seeks to foreground previously marginalized epistemologies (Darian-Smith and McCarty 2017). For instance, while many news fixers think of foreign correspondents as mentors and even friends, others offer a sharp critique of some journalists’ profound lack of background knowledge about the places they are covering.

“It’s laziness, starting by not understanding the geography and history and the culture of the country, let alone the language,” says Moe Ali Nayel, a former fixer in Lebanon. “I’ve worked with people who came here to cover major stories and didn't know the name of the Prime Minister, the name of the President. And I'm not joking.”

On top of this problem, some news fixers also note that particular journalists tend to arrive in the field with preconceived notions about the people they want to feature in their stories. “Western media [come] here with a certain mindset that these [politicians] are evil,” says an anonymous fixer working in Russia. Immanuel Muasya, a fixer working in Kenya, similarly says that journalists often arrive with the mindset that “Africa is so corrupt.” Because of this, he feels it is his job to explain the nuances of regional politics. From the perspective of critical global studies, then, news fixers can offer unique perspectives on the practice of international news reporting. We need to engage with these perspectives more often if we hope to address the inequalities that plague international journalism as a profession.

Global Inequalities

In my conversations with news fixers over the course of six years, I have been told repeatedly that international news organizations think of them as “underground” laborers, for two specific reasons. First, there is a long tradition of news organizations failing to give visible, official credit to the news fixers who help them get their stories. In other words, fixers rarely receive bylines for the print stories to which they contribute, and they are rarely acknowledged in the video news reports they help to create. While some news organizations have slowly started giving “contributor” credits to a select few, these “credits” appear in very fine print, at the end of the article. And even these credits are not necessarily guaranteed in every case.

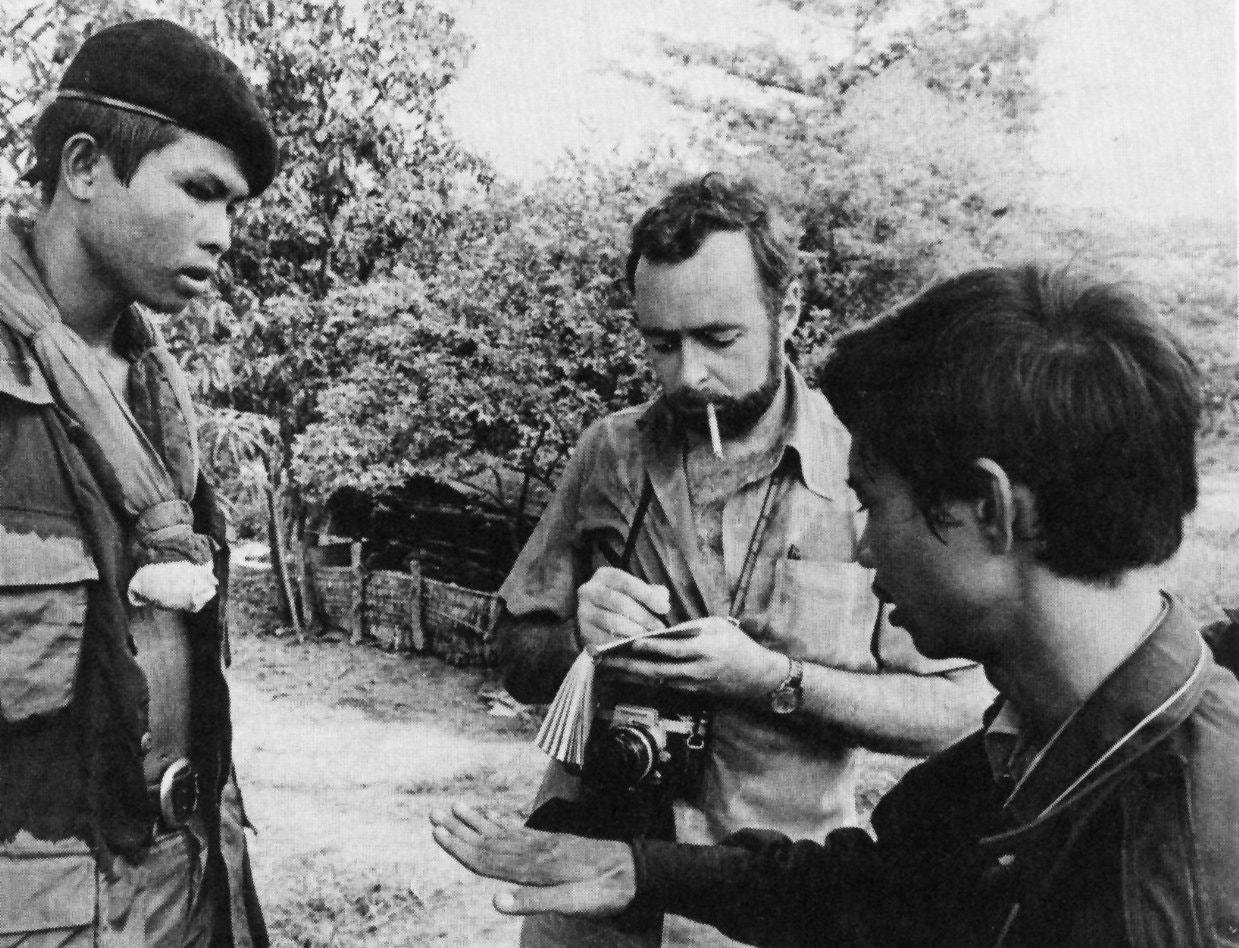

New York Times reporter Sydney H. Schanberg and his Cambodian fixer, Dith Pran, interview a government soldier before the 1975 Khmer Rouge takeover of the country. (Source: Viking Press)

Journalists and news editors often say that this practice is justifiable because fixers aren’t journalists themselves—they ostensibly do not have the same skills as foreign correspondents, or they are not doing the same level of work (Palmer 2019). This logic gets internalized by some news fixers who say that they don’t really care about getting credit (Palmer 2019). However, other news fixers see things differently.

“I was there,” says Renato Miller, a fixer working in Mexico. “I'm also a very important piece of the machinery that made it happen. . . It doesn't matter if it's a wedding, or if it's firefighting in Tijuana. Everybody who was there should be credited. Of course. It's only fair.”

Alongside this first problem, fixers also suggest that news organizations see them as underground laborers in the sense that they do not take responsibility for providing fixers with enough support and protection in dangerous environments. Some fixers justify this by saying that they are the ones who are supposed to protect foreign correspondents, and not the other way around—a logic that certainly informs the news industry discourse about hiring fixers (Palmer 2018). News organizations also tend to shrug off responsibility for freelancers more generally, arguing that they are outsourced, flexible labor, and should attend to their own safety (Palmer 2015).

Although many news organizations provide little support for fixers and freelancers, staff correspondents with major news organizations sometimes develop a strong bond with their fixers, providing safety equipment or arranging their evacuation from a region if they’re under threat. Yet these efforts can be expensive, and journalists will not necessarily be reimbursed. As of yet, there is no industry-wide standard on what news organizations owe the people they hire to guide their correspondents through unfamiliar areas of the world. From the perspective of critical global studies, this suggests that news organizations do not value fixers’ lives as much as the lives of their staff employees, which reifies fixers’ marginalization within the international news industries.

If the goal of critical global studies is to expose injustice on a global scale (Appelbaum and Robinson 2005) and to bring marginalized epistemologies more firmly into view (Darian-Smith 2015), then it makes sense for critical global scholars to turn an eye toward international journalism. This profession is plagued with its own inequalities at the industry level, but it is also a central part of the process of representing the world to the world—a practice with grave implications for global justice.

Appelbaum, Richard P., and Robinson, William, Eds. 2005. Critical Globalization Studies. New

York: Taylor and Francis. PP: 11-18.

Darian-Smith, Eve. 2015. “Mismeasuring Humanity: Examining Indicators through a Critical Global Studies Perspective,” New Global Studies. DOI 10.1515/ngs-2015-0018.

Darian-Smith, Eve and McCarty, Philip. 2017. The Global Turn: Theories, Research Designs, and Methods for Global Studies. Berkeley: UC Press.

Juergensmeyer, Mark, Ed. 2014. Thinking Globally: A Global Studies Reader. Berkeley: UC

Press.

Lim, Jie-Hyun. 2017. “What is Critical in Critical Global Studies?” global-e 10.16. See: https://www.21global.ucsb.edu/global-e/march-2017/what-critical-critical-global-studies

Palmer, Lindsay. 2015. “Outsourcing Authority in the Digital Age: Television News Networks and Freelance War Correspondents,” Critical Studies in Media Communication, 32.4: 225-239.

---. 2018. “Lost in Translation: Journalistic Discourse on News “Fixers.” Journalism Studies 19.9: 1331-1348.

---. 2019. The Fixers: Local News Workers and the Underground Labor of International Reporting. Oxford University Press.

Paterson, Chris and Sreberny, Annabelle. Eds. 2004. International News in the 21st Century. University of Lutton Press.

Thussu, Daya Kishan and Friedman, Des. Eds. 2003. War and the Media: Reporting Conflict 24/7. London: Sage.

Williams, Kevin. 2011. International Journalism. Los Angeles: Sage.