Hong Kong’s Opium Fumes, Past and Present

archive

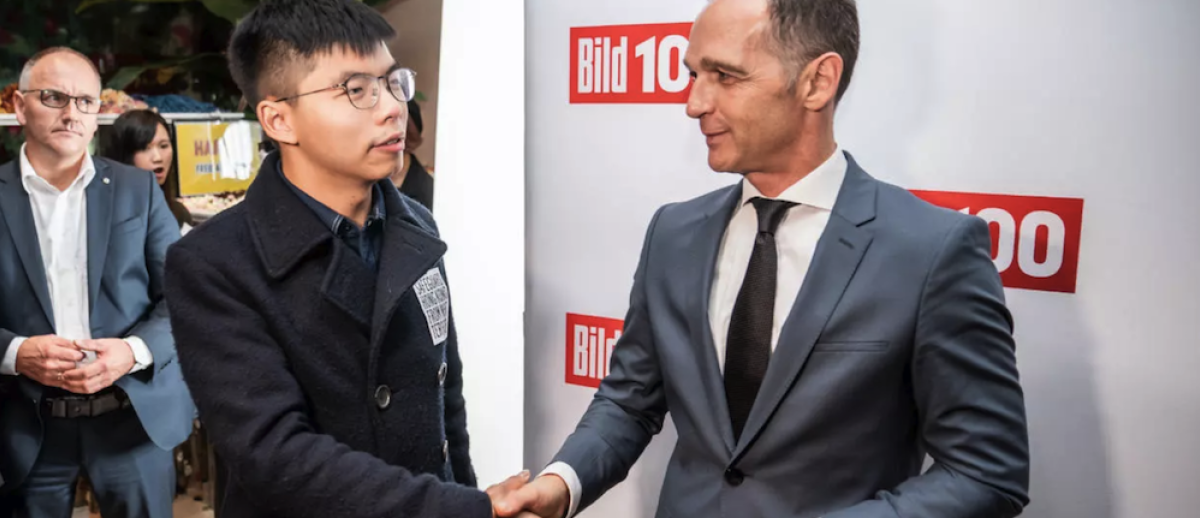

Joshua Wong with German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas in Berlin, September 2019. (Source: Michael Kappeler, dpa / AFP)

Hong Kong’s Opium Fumes, Past and Present

World politics today is a game for “deranged dotards” according to the (young but) Very Wise Leader of North Korea. Yet only girls like Greta Turnberg from Sweden and a young man named Joshua Wong (23) from Hong Kong are capable of mobilizing large numbers of followers.

Thanks to Greta we can expect all changes of the (political) weather to be transformed—later in the century—into storms of cosmic proportions, and thanks to Joshua some members of the US Congress have recently learned where Hong Kong is located on the map. Greta needs few lessons of history because her problems are located in the (fast approaching) future, but Joshua clearly misses too much of this stuff: his problem lies in the past, yet apparently nobody tells him this. Certainly not the rather irresponsible representatives of former conquerors of Chinese territories and/or large opium dealers, nor do the US Members of Congress nor the German Minister of Foreign Affairs—Germany having been the former ‘owner’ of the colony Kiaochow, once known as “The German Hong Kong.”

Against all possible political thinking and feeling and without knowing what’s relevant in Hong Kong history, these Western leaders started to publicly support the highly controversial actions of young Joshua and friends. They know that compared to what happens in many South American countries or to black people in US cities, the recent police attacks in Hong Kong are really a “luxury problem.” So while Joshua’s visits with Western adult politicians produced fantastic pictures and publicity, that was the only result.

Remarkable, however, were the reactions of specific Chinese adults—like the former student leader from the Tiananmen conflict of 1989, Han Dongfang, now 56. He told the Western press that he could not advise Joshua and his friends: “They make history now, not me. I am already history.”1 This insider strongly criticizes the extreme violence of the boys and their misbehavior against Chinese from the mainland, yet he excuses them with: “But they do not have leaders, [and] a possible mainstream is not available to stop them… they are too exhausted...” Still, Han acknowledged that they do have something to lose. This must apparently refer to something like democratization, defined as the disappearance of “governor” Carrie Lam, free elections, and specific Hong Kong laws, which they inherited from the former British Crown Colony.

Therefore, the most important question remains: What do Joshua and his many student colleagues have to lose? And even more importantly, what do the nearly one million Hong Kong street protestors (out of a population of seven million inhabitants) have to lose? What they fear losing is something that no other Chinese cities (except Macau) possess.

It was crystal clear that the protesting Hong Kongers did not worry about their future, nor about the serious effects in mainland China. No, the protesting youngsters and their crowd (with heads in a cloud?) worried about losing specific privileges obtained at the end of British rule. So, let us recall very briefly some spectacular features of this history and try to assess the basis of the present protests.2

Opium Colony

The rather “barren rock” (Gladstone) on which one of the world’s most important present money capitals has arisen was ceded in 1842 (Treaty of Nanking) by the Chinese with not one gun to their head, but rather all the guns of the British Royal Navy. It was one of the many prices China had to pay for losing the First and Second Opium Wars. Meanwhile, neighboring Macau was still a Portuguese colony and its inhabitants had for centuries already been on speaking terms with the Chinese government. (Perhaps this is why Xi Jinping recently visited Macau and not Hong Kong?)

Next, six warships and 7,000 troops were needed to guarantee British opium imports. For the next 150 years, this Crown Colony became the center of that naval force and of the opium trade. These two ‘stabilizing’ influences fostered construction of the third pillar of the Hong Kong economy: banking, insurance, and debt money. According to the Treaty of Nanking, the British received Hong Kong “in perpetuity.” It also got a territory north of the Kowloon Peninsula in lease, the so-called New Territories. Formally, it is this lease which ended a century later (July 1, 1997) and Hong Kong came back to China under the Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China.

The British steamship Nemesis bombards Chinese war junks on January 7, 1841, by Edward Duncan (1843). (Source: Wikimedia)

According to article number 109 of the Basic Law, the government shall provide “an appropriate economic and legal environment for the maintenance of the status of Hong Kong as an international financial center.” Article 1 of this law says that “the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region is an inalienable part of the People’s Republic of China,” but in article 2 China “authorizes the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region to exercise a high degree of autonomy.” For fifty years China explicitly excludes the socialist system in Hong Kong (art. 5) and protects the right of private property (art. 6). This means that, according to the agreement, ‘everything’ has to change in 2047. The present protesters, therefore, are acting quite prematurely.

David Meyer has concluded that notwithstanding the most serious turmoil in China or the world, China will keep its promises “unless some challenge to Beijing emerges from within Hong Kong.”3 Young Joshua Wong with his followers create precisely this, and could help to bring about that which they detest. But how stupid are the adults backing these youngsters: they know perfectly well, because it concerns their day job, that China remains the largest owner of Hong Kong dollars (25%), which makes her interest in the survival of the city of “immense interest”; and that the Bank of China transferred its international unit from London to Hong Kong so that on this promontory not only Hong Kong’s, but also the PRC’s mega-immense holdings of USA dollars could be managed in and through the Hong Kong debt market. What happens to the city of towering banks if China ‘simply’ decides to install this debt market somewhere on the mainland, using Joshua Wong as pretext?

[W]hat do the nearly one million Hong Kong street protestors (out of a population of seven million inhabitants) have to lose? What they fear losing is something that no other Chinese cities (except Macau) possess.

The above concerns the economy of Hong Kong, but what about its historical sociology or its “democratic past”? To take one quote about life in that colony:

And all the British exhibited disdain for the various lesser breeds who shared the colony with them, jumpers on the band-wagon of Empire, the sprinkling of Eurasians and Portuguese, Parsees and Sindhis, Jews and Armenians, Frenchmen and other disreputable Europeans... Sir Vandeleur Grayburn of the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank is said to have commented, “There is only one American in the Bank and that is one too many.” But in particular they looked down upon the 98 per cent of the population who happened to be Chinese.4

In the most literal sense, the British colonial elite lived in Hong Kong high above the vulgus. The latter had no (political) rights whatsoever and were overruled in every sense by a British Governor with his supreme power and a direct line to the Colonial Office in London. The other Europeans in the city also had no political rights, only some (racist) privileges. This dictatorship was “legitimized” with the rationalization: “If We have to give you, Europeans, democratic rights, then we have to do this with the Chinese also, which is impossible!”

And then there was the opium business, which was not only destined for China but was soon also exported to Southeast Asia and the USA. In both Hong Kong and Shanghai the British policy of transforming opium from a luxury good into a bulk commodity was definitely organized and financed. This policy followed the example of the Dutch, and with great success. Silk, raw cotton, and rice were the common products in this trade, but opium comprised the major balance of general commodity exports.5

After World War II and the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong soon became again a city with the “triangular economy”: a Crown Colony for British naval power, banks, and opium. All opium gangs from the mainland had emigrated to this new world distribution center of opium, heroin, and other narcotics, and they did not disappear after 1997. The opium fumes still rise from this city not affected by the protests of young Joshua Wong and his comrades.6

1. Interview in the best German weekly Die Zeit, November 21, 2019, 5. Han Dongfang qualified himself as “a worthless Dinosaur” (“ein wertloser Dinosaurier”) compared to these young kids, who know that there is no way back.

2. For the sources of the following history and much more about Hong Kong and the British Empire see Hans Derks, History of the Opium Problem. The Assault of the East, ca. 1600-1950 (Boston/Leiden: Brill, 2012), in particular 72-86 and passim.

3. David R. Meyer, Hong Kong as a Global Metropolis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 245.

4. Quoted in H. Derks, History of the Opium Problem, 74.

5. Idem, 75 ff. and Meyer, 61 ff.

6. After 1997 the Chinese government of Hong Kong apparently suggested that suddenly Hong Kong’s opium history disappeared: no data are available. Still, for the present situation the activities of the “bell-ringer” Hervé Falciani is highly important. He disclosed the many criminal backgrounds of the very large Hong Kong bank (HSBC) which is from its earliest days (ca. 1840) involved in the international narcotics trade. See Eric Toussaint, HSBC, the bank with a shameful past and a scandalous present, www.cadtm.org (8 June 2014). For the earlier British opium trade see N.J. Miners, “The Hong Kong Government Opium Monopoly, 1914-1941,” in: The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 11 (1983), 275-299. See also, Harold Traver, Jon Vagg (ed.) Crime and Justice in Hong Kong (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), 42-57. Traver provides the top of the iceberg concerning the seizures of dangerous drugs (opium, morphine, heroine, etc.) in Hong Kong from 1948 to 1989. For the “practice on the streets” it is good to combine this kind of literature with a popular biography of the dealer Peter Hui by Jonathan Chamberlain, King Hui. The man who owned all the opium in Hong Kong (Hong Kong: Blacksmith Books, 2010).