The Politics of Nostalgia: Memory Restructuring in the Eastern Mediterranean

archive

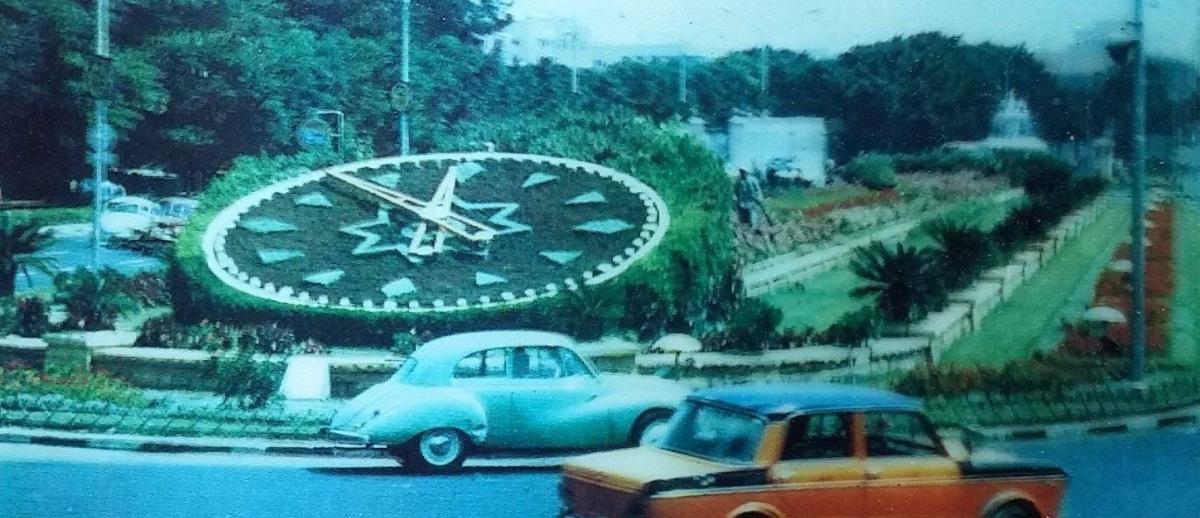

vintage photo of Sa'at Al Zouhour Square, Alexandria, Egypt.

The Politics of Nostalgia: Memory Restructuring in the Eastern Mediterranean

Shows of solidarity have often been made by a conscious or unconscious reappropriation (or in other terms, the “reterritorialization” and “deterritorialization”) of collective memory. Shows of solidarity, both obvious or subtle, are performed by collectives as well as individuals, and manifest endlessly, from transnational “infectious” protest to the transfer and re-adaptation of cultural forms.

In the modern history of the Levant, shows of mnemonic solidarity have accompanied milestone anti-colonial and decolonizing moments, with countries across the grids of British empire often drawing inspiration from each other. In the early twentieth century, for example, Tagore’s call for religious unity was translated by Egyptian intellectual Taha Hussein into a call for religious harmony, while Gandhi’s concept of non-violence was appropriated by Egyptian feminist Doria Shafik to stage hunger strikes for women’s rights. Meanwhile, Pan-Africanist and Negritude intellectuals connected to the Civil Rights Movements in the United States by harnessing the memory symbols of pre-slavery civilizations in Egypt and Zimbabwe. During the mid-1950s, similar solidarity appeared across members of the Non-Aligned movement claiming a shared past of imperialist oppression. This manifested in an increase of scholarship and translation of literary works across Cuba, Chile, Egypt, Lebanon, Turkey, and India. Yet again, at the cusp of the twenty-first century, the slogans of the Arab Spring, themselves often drawing on slogans of people power from the Velvet Revolution, reverberated in North Africa and across to London, Madrid, and New York.

Such actions are relatively tangible to see. Less tangible is the silent, sometimes unconscious form of resistance playing out in the re-appropriation of specifically nostalgic memory symbols. In the Levant the past couple of decades have witnessed a perceptible rise in nostalgia for a lost modernist cosmopolitanism.

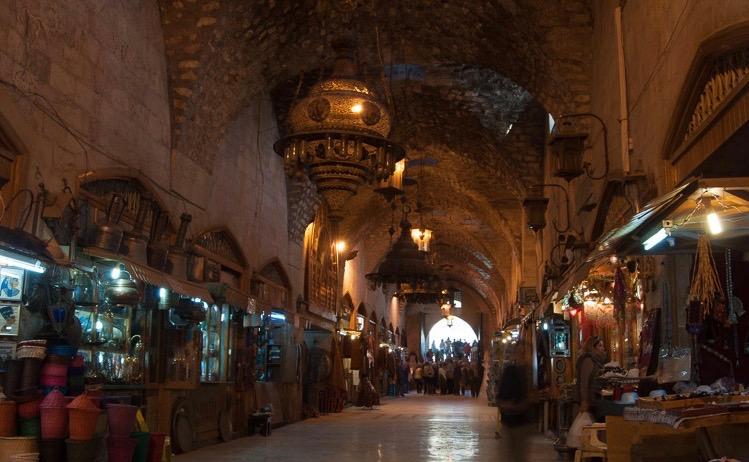

Barely perceptible, this yearning for some better past has appeared in literary writings, historical television series, and social media groups. A quick look at Facebook will unearth dozens of pages devoted to sharing image-tropes which have now become familiar: yellowing, black-and-white faded photographs of wide, clean, unpopulated boulevards, glittering soirees of the royal family and moneyed classes, or even of unknown European residents from the early twentieth century, and buildings and neighborhoods from a time before globalized “gentrification”. Image upon image in sepia accumulate an easy to locate idealistic narrative: dignified temples in Damascus and bustling markets in Aleppo, glamorous boutiques in downtown Alexandria and well-populated synagogues in Cairo, Peggy Swing dresses and upturned hairdos on mascara-eyed women in well-tended public gardens, a floral, pre-Civil War centre ville in Beirut.1 Framed by discourses of weeping melancholia, impoverishment, and exile, the familiar visuals have come to iconize the mourning for a “lost” Ottoman-era cosmopolitanism in the Middle East. This display of past souvenirs undoubtedly has different purposes depending on the memory agents—from independent filmmakers to state cultural institutions– who are responsible for generating it. Produced or mimicked willingly by the public, however, this nostalgia—with its implicit disapproval of the current status quo—becomes resistance to a state of things the citizen cannot change. The impact lies in the act of contrast. “Look at us then,” the faded glitter of the daguerreotypes of lost communities seems to say, “and look at us now.”

Pre-civil war al-Madina Souq market, Aleppo, Syria.

Traditional scholarship on nostalgia makes it out to be something suspicious, even outright dangerous.2 As an emotion nostalgia is, of course, pretty useless. The longing for a past that never existed? No strategy seems less practical. To imagine a golden past by erasing its violence? No action seems less ethical. More importantly, nostalgia has been used politically to justify anything from the persecution of Jews to the lynching of black people, and from establishing anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant policies to the subjugation of Palestinians. The idea of condoning nostalgia can thus hardly be anything but repulsive to those interested in learning from the past. Methodologically-speaking, approving of nostalgia also implies approving of the idea that forgetting is as important as remembering. This goes against the grain of sticking to the evidence-based record required by the historical sciences. Finally, for those interested in action, looking backward seems much less conducive than, even irrelevant to, the more exigent necessity of looking at the ground beneath our feet. In such contexts the idea of a progressive nostalgia couldn’t sound more absurd.

Nostalgia, though, does not necessarily carry inherent positive or negative values. Like memory, nostalgia is a tool: and a tool is neutral. The defining value of using a tool comes from intent and objective. When the nostalgia for a lost past is carried out willingly by members of the public in particular authoritarian contexts, it can indicate something more than wishful thinking, ignorance about the past, or escape from accountability. It is, rather, a willful act of memory restructuring. It is an intentional political act of locating oneself as a political being in the wider world, albeit through the very feeble opportunities possible, in order to imagine change in a rejected present. Nostalgia does not just reiterate the loss of a past (whether or not this past actually existed) but points to resistance against or rejection of the political status quo. Nostalgia—not without irony—can then point to specific political action as much as it reflects the lack of citizen capacity.

Nostalgia does not just reiterate the loss of a past (whether or not this past actually existed) but points to resistance against or rejection of the political status quo.

For lack of a better name, “resistance nostalgia” is the attempt to recover a golden image of the past while erasing its more unpleasant aspects for the sake of a future that one longs for but cannot articulate specifically because of authoritarian contexts. In this way, nostalgia can be used to overcome censorship in policed societies. It’s easier, after all, to criticize gentrification projects manned by powerful elites by talking about the beautiful buildings of yesterday. The action of longing for a different reality is articulated in such codes, which themselves become validated by seeming to refer to an organic, locally-possible state in society. Because these alternate visions are local, they cannot then be considered treasonous or imported or impossible, even if they do seem to go against the grain of the current status quo. In politically impotent contexts, nostalgia can also build empathy for voiceless victims. Pictures of happy “natives” before a military occupation, for example, give victims of political occupation a way to write some history for themselves, and give other people a way of expressing solidarity with this cause. In politically impotent contexts, nostalgia is a reminder that the power of memory rages within us. If using memory as testimonial is imperative for political accountability, nostalgia can be important for the healing process of societies. It makes us forget things that we need to forget so societies can move on.

Resistance nostalgia is also a transnational phenomenon. It can appear, unrelatedly, in different cultural locations and is therefore comparable. It can also be transferred, when the same nostalgic tropes are used in new contexts. One example is the rich corpus of literary texts on Alexandria, Egypt, which have helped draw a nostalgic representation of an ideal cosmopolitan city during the early twentieth century, suspended in time and tide, and populated with a multiplicity of ethnicities and religions. Written in different languages, including French, Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, and English, and published for different audiences and wildly different purposes around the world, the texts still use the same tropes. Nor is this literary ethos specific to Alexandria, even though the Alexandrian nostalgic imaginary has been helped by having been fostered by giants of the world literary canon like C. P. Cavafy and Lawrence Durrell, in whose footsteps many of the more recent writers currently follow.3 Rather, the same can be said of similar cities across the Eastern Mediterranean, notably Jaffa, Izmir, and Athens, all of which have their own nostalgic modernisms with remarkably similar tropes, and all seeming, strangely and contradictorily, to long for a multi-cultural community that was, like all communities, built on hierarchies and sometimes outright injustice. Is this nostalgic sharing of souvenirs, bad history or good politics? There is no clear answer. What nostalgia really is, is human, global, unstoppable.

Resistance nostalgia... can appear, unrelatedly, in different cultural locations and is therefore comparable. It can also be transferred, when the same nostalgic tropes are used in new contexts.

This is when social or political objective becomes paramount. Objective is what refines good nostalgia from bad nostalgia. Memory restructuring is inevitable; the ethical purpose to which it is put to use is not. The ultimate judgement for nostalgia (or memory-restructuring) is the policy to which it leads.

The role of memory itself is an endless explorative territory, but will remain subjective and based on those who manipulate it. We use memory collectively within a political society to produce standards on how we want to live together, and where we want to be in the future. The collective use of memory in a given society is, then, a political and therefore ethical action. If, as Patrick Manning once said, history does not change but the way we interpret it changes continuously, it behooves us to remember that we are in charge of our vision of the past, not vice versa. Both memory and history are a vital part of our social fabric, our everyday realities, but they are malleable. They are, in other words, our vision of the world in which we live, and the world we would like to create. In the face of this horrendous responsibility towards history and the future, the question of what we need to remember as well as what we need to forget undergirds both the prospect and the ethics of humanity. The line between what we need to remember and what we need to forget is extremely fine, but it is one we need to be conscious of before we dismiss, and underestimate, the power of nostalgia.

1. Examples of Facebook groups are endless. Despite the difference in purpose, and profession or official function of their administrators, popular examples of Egyptian pages include: “Alexandria Live, “Alexandria 1900” or “Monarchy & Dynasty”.

2. See, for example, the range of work on nostalgia by Svetlana Boym.

3. See, for example, on Alexandria: Harry Tzalas, Farewell to Alexandria and Seven Days at the Cecil; Jacqueline Cooper’s Cocktails and Camels, Andre Aciman’s Out of Egypt, Lucette Lagnado’s The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit, and Ibrahim Abdel Meguid’s Alexandria trilogy.