The Citizens Have Spoken

archive

The Citizens Have Spoken

Like most of my friends and family, last November 8 I watched in horror as Hillary Clinton went from being the favorite to realizing that Donald Trump would win the presidency, and that his party would have control of the Senate and the House of Representatives. I felt betrayed by my fellow citizens and fearful for all the racial, sexual, and ethnic minorities and women who would undoubtedly suffer from the fallout of these election results. Slowly I began to recognize the source of my pain: I had fallen prey to the seduction of citizenship. Even though my career is partly defined by my intellectual interest in the dark side of citizenship, my heart is always vulnerable to its saccharine promises. I am surrounded by these promises, by those who trumpet the potential for citizenship reform, the necessity to expand citizenship, and the noble hope of an inclusive society.

On the other hand, the technical capacities of citizenship to control the political, economic, and cultural fields make it not simply a tool of inclusion but a weapon that can be wielded with great precision against racial and ethnic others, particularly those marked by immigration. People like me.

This dark side of citizenship—injurious, painful, exclusionary—is not an aberration or a glitch in the mechanism of liberalism that can be fixed with policy adjustments and a tweaking of our political culture. This darkness is inherent in citizenship as a tool of government, a shadow that has grown alongside citizenship’s more Enlightened sides. This is why explaining the significance of Trump’s election is partly about explaining citizenship and its history.

Pericles' Funeral Oration, by Philipp Foltz (1852). Wikipedia

The technical capacities of citizenship have been accumulating for some time. The equivalence of citizenship and political agency, for instance, was constituted by the Greeks, who, in Engin Isin’s words, began the tradition of granting the citizen “the right to being political.” It is in this often idealized Classical world where we find the first version of a tension of values between racial nativism and inclusive emancipation.

In Athens, the citizen was imagined always in relation to others: those who did not belong to the city, such as foreigners, slaves, and travelers; those who lived outside the city walls, which in Athens included workers and craftspeople on whom the city depended but who were not protected by the city’s infrastructure; and those who did not have the personal characteristics, regardless of ancestry, to be citizens, a large group that in Athens included women and the offspring of slaves (slaves themselves were often imagined as foreigners). Most people in the social world we now know as Classical Greece were not citizens. Yet, by and large, citizens wrote the political history of Athens and, predictably, this history speaks of citizenship for the most part in terms of the virtuous capacity for equality that it allowed. Indeed, those wonderful Athenians were firm believers in what today we recognize as racist nativism, but they were also accomplished publicists of the virtues of equality under the law, even if the polites (the citizens) were never more than a handful of people.

...the technical capacities of citizenship to control the political, economic, and cultural fields make it not simply a tool of inclusion but a weapon that can be wielded with great precision against racial and ethnic others, particularly those marked by immigration.

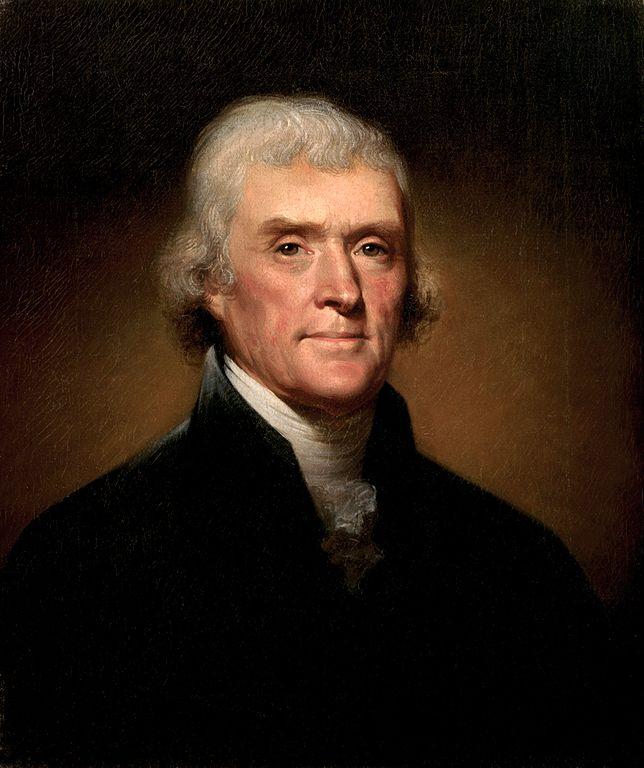

Citizenship in Classical times possessed all the elements that would be necessary to function as a tool for domination and emancipation during the eras of colonialism and the Enlightenment, respectively. This included a list of great publicists, from Plato, Aristotle, Herodotus, Thucydides, Polybios, Plutarch, Sallust, Livy, Cicero, and Tacitus, who would influence John Locke and Jean Jacques Rousseau and would be mandatory reading at the time of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. The virtues of equality, broadly debated by the Classical authors, were indeed understood much better by Enlightenment thinkers than citizenship’s capacities to enact racial nativism. Nowhere is this more evident than in how Jefferson’s clarity of vision on equality contrasts with his intellectual contortions when he discussed slavery. How can the writer of the Declaration of Independence be the same man who argued that emancipation would have to be democratically chosen by slaveholders?

Until recently, the list of illustrious publicists of citizenship had no equivalent when it came to articulating its dangers. Discussions about the connections between citizenship and racial nativism (as well as sexism) were mostly non-existent in Classical times, and Enlightenment thinkers were mostly blind to their own racist xenophobias as is clear in the cases of Locke, Kant, Hegel, and Jefferson. Consequently, the idea of citizenship comes to us moderns as a political tool for good—still perfectible but fundamentally noble—rather than the way it should be seen: as a double-edged sword that can nevertheless foster the most effective forms of exclusion.

Moreover, the egalitarian capacity of citizenship has been credited by some historians and theorists of the nation-state with providing the affective ground for the emergence of the nation form. Benedict Anderson famously notes that monarchic and religious ways of organizing the political were substituted by new sets of secular ideas about politics and kinship and new ways of experiencing the social. Some of these secular ideas about politics we now recognize as nationalism, and some of the new ways of experiencing the social included new kinship structures, which Anderson calls “imagined communities,” made possible by modern ways of experiencing kinship. Yet, Anderson fails to reconcile the horizontal camaraderie that nations seem to engender with the hierarchical organization of life and systems of inequality inherent to all nations, the dark side of citizenship. Others, however, are better at explaining de facto national vertical arrangements and the nativisms on which these are based.

Etienne Balibar and Immanuel Wallerstein argued that the emergence of the nation-state was linked not simply to the rise of the bourgeoisie, central in capitalist societies, but to the fact that capitalism is rooted in what Wallerstein has been calling since 1974 the “world-economy.” Balibar and Wallerstein believe that this world economy “is always already hierarchically organized into a ‘core’ and a ‘periphery,’ each of which have different methods of accumulation and exploitation of labour power, and between which relations of unequal exchange and domination are established.” This means that, as Balibar would restate it, “every modern nation is a product of colonization: it has always been to some degree colonized or colonizing, and sometimes both at the same time” (Balibar 1991, 89). The core-periphery basis of capitalism helps Balibar and Wallerstein theorize racial and ethnic difference as seminal to nation-states, for it is the core-periphery ethno-territorial hierarchies that culturally legitimize and give legal form to racial and ethnic hierarchies.

...according to scholars of coloniality, racialized law has been as important a legal foundation for the U.S. nation-state as has, for instance, Jeffersonian liberal ideals of equality or Madisonian republican ideas of civic virtue.

Enrique Dussel, Anibal Quijano, and Walter Mignolo have expanded on the implications of the Wallersteinian “world-economy” for the Americas, and have used the term “coloniality” to refer to the way colonial domination between the European core and the American periphery was concretized through law and administrative processes. Just as relevant, these Latin American thinkers also argue that racialized colonial law and administrative processes survived independence movements to become part of the legal and policy frameworks of nation-states. Hence, according to scholars of coloniality, racialized law has been as important a legal foundation for the U.S. nation-state as has, for instance, Jeffersonian liberal ideals of equality or Madisonian republican ideas of civic virtue.

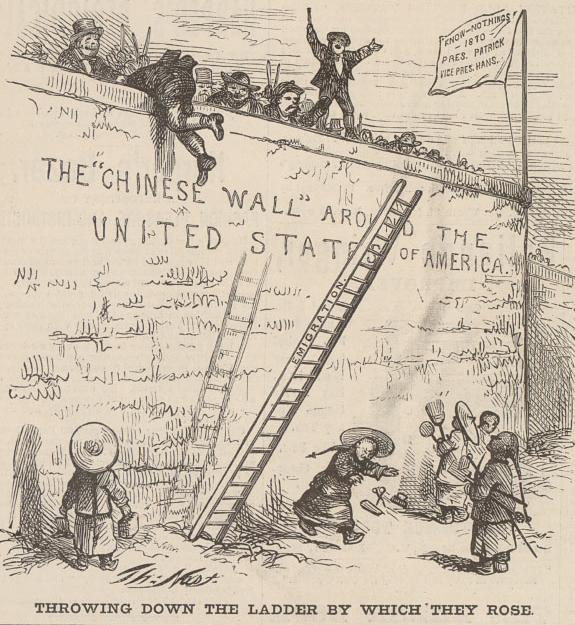

"Throwing Down the Ladder by Which They Rose" Thomas Nast, 1870. Credit: Illustrating Chinese Exclusion

Thus the old Greek tension between racial nativism and egalitarianism is the unsolvable riddle on which we have built our political world. Trump is not an aberration. Neither is nativism. Racial nativism in the United States today is the dark side of citizenship and an expression of core-periphery relations within a state, showing how coloniality continues to shape the nation form.

Trump and his supporters have understood and manipulated this dark side. They have rhetorically exploited the primordial argument that the citizen is the opposite of the other, that the citizen is inside the city walls and the other is outside. In an age of immigration and transnationalism, an age of eroded walls, Trump has used fear to reconstruct the walls within the hearts of citizens, and citizens have acted against the barbarians with the legal tools of politics. The citizens have spoken. Let the pain begin.

Etienne Balibar and Immanuel Wallerstein. Race, Nation, Class: Ambiguous Identities. Trans. Chris Turner. (London & New York: Verso, 1991)

Enrique Dussel. Ethics of Liberation: In the Age of Globalization and Exclusion. (Duke University Press, 2013)

Walter Mignolo. The Darker Side of the Renaissance: Literacy, Territoriality, and Colonization. (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1995)

Anibal Quijano. “Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism and Latin America.” Nepantla: Views from South 1.3 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2000)