Europe’s Melancholias and the Crisis of Multidirectional Memory

archive

Holocaust Memorial in Berlin, Germany

Europe’s Melancholias and the Crisis of Multidirectional Memory

In the global memory space “historical actors and memory activists are linked […] even though no de facto entangled history exists,” according to Jie-Hyun Lim. This is both the core insight and the central promise of the mnemonic solidarity project: If we can imagine a shared history we can envision a shared future. This essay invites reflection on a challenge to mnemonic solidarity that has arisen in those spaces of actually entangled histories where Michael Rothberg first identified “multidirectional memory”: societies where the heirs to colonial and Holocaust histories now live together.1

Holocaust is a key term in the construction of entangled memories today. Holocaust awareness and practices of remembrance that circulate globally can promote cosmopolitan values, and “multidirectional memory” opened up an important discussion of those possibilities. But Holocaust discourse continues to provide a language for articulating hierarchies of victimhood.

In Europe it is by colluding in denying or relativizing the Holocaust that nationalism is currently asserting its claims, perhaps most obviously in the post-socialist states. While the 2018 Polish law criminalizing statements about Polish complicity excited international attention, the Hungarian case seems peculiarly characteristic of the current conjuncture: There the House of Terror (opened 2002) and the new Holocaust museum, the House of Fates, have both been criticized for downplaying Hungarian agency in dictatorship and genocide. Meanwhile, Viktor Orbán’s government goes into the centennial year 2019 with educational and cultural programs mourning the Treaty of Trianon that reduced Hungary’s size and influence while granting it independent statehood after World War I.

We might call this post-imperial melancholia. In 2005 Paul Gilroy diagnosed the malaise besetting Western Europe as “postcolonial melancholia”: a mental state in which mourning for a lost empire has turned into an incapacity to accept the reality of the multicultural Europe that colonialism produced.2 Official memory in Hungary and other post-1918 successor states is seized by nostalgia for a “white, Christian” Europe which is similarly schizophrenic: Invoking their historical role as its defenders (against crusading Islam), they repress the memory of the mixed cultural and faith communities fostered by Europe’s multi-ethnic empires before 1918 and obliterated by genocide and forced migration between 1939 and 1949.

The remaining blank spaces in historical memory are easily filled by a new old-fashioned antisemitism, publicly licensed by rhetoric like Orbán’s attacks on George Soros. But it is not only in Eastern Europe that antisemitism is on the rise and increasingly perceived as a threat by European Jews.

At the same time, in the post-colonial metropolises to the west, the melancholia that Gilroy hoped might be overcome by “ludic, cosmopolitan energies and democratic possibilities” seems to have the upper hand. In the UK, it has lately taken material form in the Brexit referendum (an outcome principally of anti-immigration politics) and in the scandalous deportations of children of the “Windrush generation.”

There are good reasons for those who are targets of the new intolerance to cooperate. But here the project of mnemonic solidarity finds its optimism confronted by the decay of solidary values and practices that drew on memories of oppression in the past. Jewish social and political activism historically encompassed engagement in black and colonial liberation struggles. Colonial and black diasporic activists and intellectuals fought to defeat Nazism and engaged in sustained dialogues with the Holocaust experience during the twentieth century. In the twenty-first century, though, Holocaust discourse is often inhibiting solidarity rather than facilitating it.

...mourning for a lost empire has turned into an incapacity to accept the reality of the multicultural Europe that colonialism produced.

This has much to do with a moment in which we are having to come to terms with the actual pastness of the Holocaust. The generation of living witnesses is dying out—a particular anxiety for a memorial and educational practice that has privileged victim testimony. To be sure, since the 1990s institutionalized forms of remembrance and commemoration have sustained “Holocaust” as an embodied presence in Europe and America, by creating a discursive framework that enabled new generations to become witnesses and transmitters of memory.

Perhaps for that very reason we seem have entered a phase of post-Holocaust melancholia. In this frame of mind, the memory claims of non-Jewish victims of Nazism (on the one hand) and challenges to the legitimacy of Israel’s domestic and foreign policy (on the other) provoke nostalgia for an imagined historical moment in which global acknowledgement of the Holocaust as a Jewish catastrophe was accompanied by a consensus in the West that the historical mission of the survivors was properly embodied in the new nation state. The response to the loss of that moment is a renewed hierarchical victim discourse—articulating moral authority in terms of Jews’ peculiar claim to victim status. This in turn pre-empts visions of the present that situate Jews as other than victims. And it fixes on unconditional support for Israel as the precondition for moral and political legitimacy in public discourse.

The independent psychological dynamic of this post-Holocaust melancholia is visible in the intensity with which the question of the nature and extent of antisemitism within the British Labour Party has recently been debated. The debate turned first on the Party’s reluctance to accept in full the definition of antisemitism formulated by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, which yokes the Holocaust past to the present and future of Palestine by calling certain propositions about the state of Israel examples of antisemitic speech. These include both challenges to the legitimacy of the state of Israel itself and statements that deploy the language of Holocaust memory to challenge Israeli ethno-nationalism and occupation policies.

Holocaust discourse continues to provide a language for articulating hierarchies of victimhood.

The linkage between Holocaust piety and the defence of Israel has particular plausibility for British Jewry, which has since 1945 been more strongly pro-Israel than other diasporic communities (although there are also strong Anglo-Jewish voices in dissent). But in the UK, as in the wider Atlantic memory space, it contends with the voices of people for whom the Holocaust is not any kind of memory. For Americans and Europeans with family histories of colonial oppression and violence, the sufferings of displaced and besieged Palestinians are more immediate than the historical trauma of Europe’s Jews. One result of this is, indeed, lack of sensitivity to and even a new license for antisemitic language, imagery and actions in anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist discourse. Another is that the charge of antisemitism is experienced as a silencing mechanism. In August 2018 an open letter signed by 84 British Black and minority ethnic organizations, invoking common histories of colonialism and racism, insisted that freedom to choose the terms in which they comment on Israel was indivisible from the freedom to express their own needs as minority communities in Britain.

There is a real political and ethical challenge here, but lately we have seen a series of stand-offs. Another example from the summer of 2018 in the UK illustrates both the problem and the possibility of creative responses:

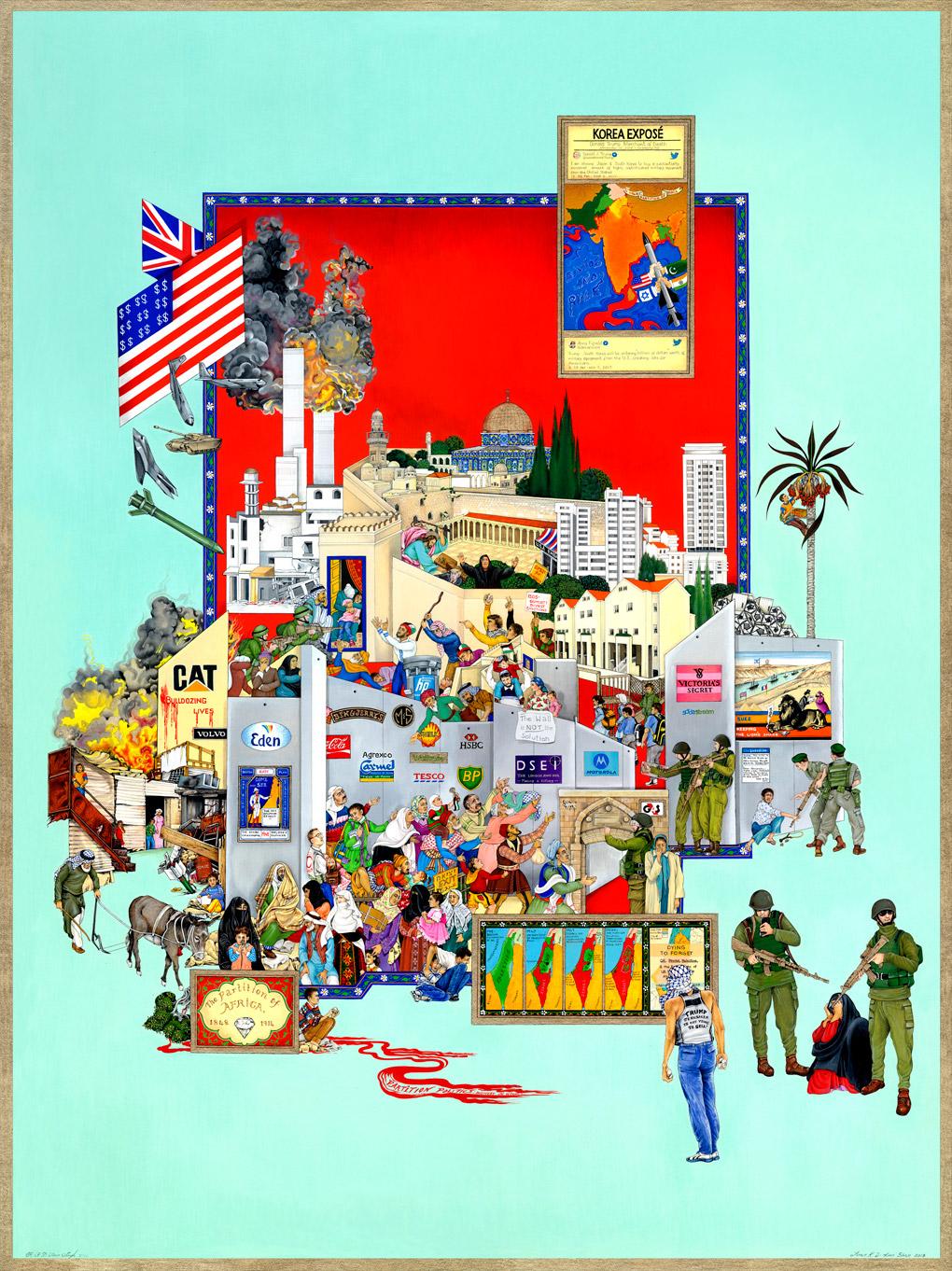

'Partition Politics – Business as Usual', © The Singh Twins (image provided by the artists)

A public gallery was asked to remove a painting by British artists The Singh Twins from a temporary exhibition on the grounds that the image was antisemitic. The exhibition’s theme was the historical connection between colonialism, capitalism and luxury consumption, and the picture in question, entitled Partition Politics – Business as Usual, is a conspectus of partitions carried out by colonial powers, exploited by international capital, and contested by non-state actors. Images of the occupied West Bank are at the center of a design that also refers to the Scramble for Africa, the partition of India, and the Western intervention in Suez. While it draws on memories of colonial and post-colonial violence, the picture foregrounds the international arms trade as the driver and beneficiary of regional conflicts.

Viewed through the lens of Holocaust memory, it looked antisemitic to at least one viewer. In fact, the gallery rejected the claim of antisemitism. And indeed, in its insistence that those histories really are materially entangled, Partition Politics seems to me to be in keeping with a spirit of mutual recognition between heirs to the Holocaust and to the Nakba.3 The only figures in the picture who are identifiably Jewish occupy the very center of the picture, and they are holding a sign that reads “The wall is NOT the solution.” However, the UK gallery felt obliged to post a disclaimer at the exhibition entrance.

In this stand-off, mnemonic solidarity depends on going beyond the necessary reminders that racism (like suffering) is indivisible to identify grounds for dialogue. My own encounters with Jewish and Roma Holocaust survivors—too often contenders in a hierarchy of victimhood - confirm that vernacular memory is inherently generous. Wherever we can, scholars and activists need to connect face-to-face conversations to critiques of the discourses of national and community ressentiment that constrain empathy and the social and geopolitical practices of power (“partition politics” in the widest sense) that persistently force us into the positions of “victims” and “perpetrators.” But this presents particular challenges in the Global North’s spaces of contending diasporas. Here, the passing of the Holocaust survivor generation really does leave us with an asynchrony of witness, at a moment where the traumas of the past and the present urgently need to explain themselves to one another.