Urbanization of Empire: Plantation, Space, and Racial Terror

archive

Urbanization of Empire: Plantation, Space, and Racial Terror

Rethinking Urbanization Beyond European Industrialization

Urban modernity has often been interpreted as the direct outcome of European industrialization and the expansion of cities. Such readings tend to locate the urban as a specific empirical form—the industrial city—and to understand its generalization as a process relatively autonomous from colonial experience. This essay proposes a displacement of this narrative by approaching urbanization as a broader historical process, inseparable from the colonial constitution of modernity. Drawing on Henri Lefebvre’s distinction between city, countryside, and the urban, it argues that the urban does not designate a delimited spatial form, but rather a historical virtuality: the generalization of capitalist social relations in space (Lefebvre 2019).

This distinction is fundamental to the argument developed here. The classical opposition between city and rural refers to specific historical forms, whereas the urban operates as an epistemological category capable of traversing them. Urbanization, in this sense, subordinates both the city and the countryside to a single historical totality, reorganizing social, spatial, and political practices in accordance with the requirements of capitalist accumulation. By situating the urban as a process, it becomes possible to rethink the genealogy of spatial modernity beyond the European-industrial horizon and to reposition colonial experience at the center of analysis.

The Colonial Plantation as a Key Socio-Spatial Configuration

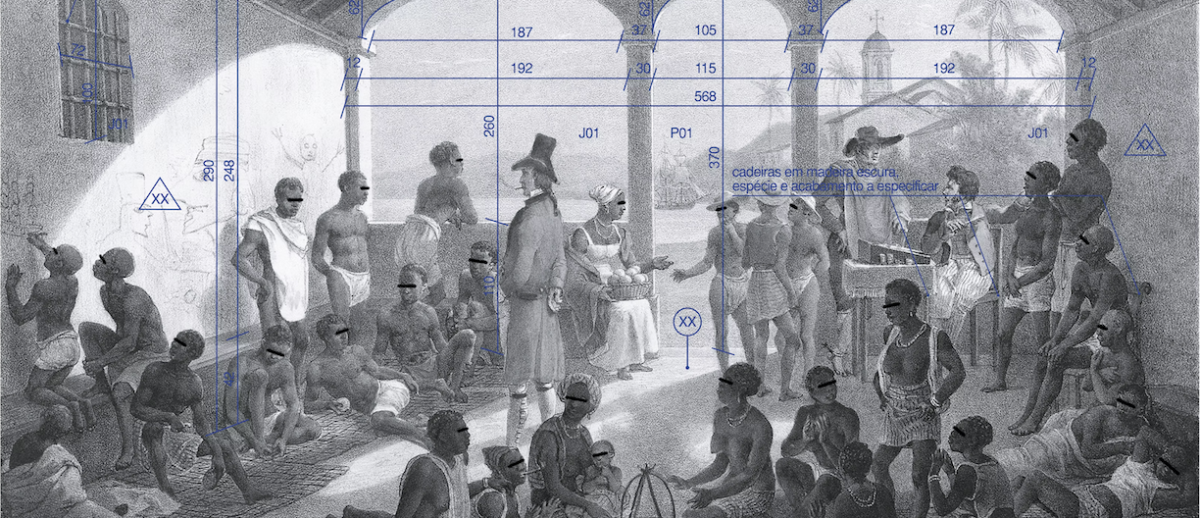

It is in this context that the colonial plantation emerges as a decisive analytical object. Far from representing a residual agrarian form or an archaic stage of capitalism, the plantation is understood here as a specific socio-spatial configuration in which relations that traverse capitalist modernity are condensed with particular intensity. Within it, economic production oriented towards the world market, systematic racial differentiation, and the continuous administration of violence are articulated. The plantation does not explain modernity in its entirety, but renders visible, in concentrated form, principles that would later be rearticulated in other historical and spatial contexts.

The production of plantation space is inseparable from the elaboration of regimes of racial depreciation. Racialization does not operate as a secondary marker, but as an organizing principle that structures asymmetric positions within the social order. Certain populations are constituted as fully human, entitled to protection and institutional recognition; others are positioned as exploitable lives, structurally exposed to expropriation, coercion, and death. This differentiation is not abstract, but materially inscribed in territory, regulating circulation, permanence, and access to the means of life reproduction.

To understand how this regime is spatially articulated, it is productive to mobilize the notion of the “symbolism of the center,” as formulated by Peter Fitzpatrick. In his analysis, Fitzpatrick demonstrates that every regime that institutes a centrality simultaneously produces that which exceeds it: the exterior is not a natural given, but a construction necessary to the affirmation of the center (Fitzpatrick 2007). By displacing this conceptual metaphor into the field of spatial production, it becomes possible to think of modern spatiality as a regime that affirms certain territories as central—rational, productive, civilized—while producing others as functional excesses, incomplete or lacking form.

In the context of colonial expansion, this logic acquires particular density. Indigenous-diasporic lands and bodies, as well as territories described as “empty” or “unproductive,” are constituted as exteriors subject to appropriation and reorganization by colonial regimes of power, whose principles would later be rearticulated by capitalist urbanization. This exteriority is not simply excluded; it is positioned as a reserve for appropriation.

The etymology of the term urbanum, associated with the foundational gesture of territorial demarcation, preserves historical traces of this logic. The urbanum was a section delimited by the furrow drawn by the plow of Roman sacred oxen, whose boundary distinguished the territory of production from the territory of collective life (Monte-Mór 2006). Indeed, the most important moment of the Roman city’s founding ritual was the opening of the sulcus primigenius, the initial furrow. This symbolic act of organization established a spatial separation between the world of life and the world of production, between the urbs and its negative. The initial distinction was demarcated between the urbs—the founded city—and the rur, the Roman land beyond the plowed boundary.

The furrow traced by the plow in the Roman founding ritual institutes an inaugural separation between inside and outside, between the space of protected life and the space of exploitation. This etymology does not provide a causal explanation of modernity, but functions as a historically situated conceptual metaphor for understanding how regimes of alterity are inscribed in the production of space.

The notion of the frontier occupies a central role in this process. Before stabilizing as a juridical-political category, the frontier designated the margin of the inhabited world, the limit beyond which the known became indeterminate. With colonial expansion, this margin is transformed into a frontier dispositif: a set of practices and knowledges oriented toward the translation, classification, and administration of what exceeds the central order. The frontier thus operates as an epistemic technology through which alterity is reinscribed within a dominant regime of intelligibility, enabling its exploitation, containment, or elimination.

The genealogical analysis of the plantation, however, requires further displacement. While it allows for the identification of a historical configuration in which regimes of violence and differentiation manifest in concentrated form, it is also necessary to observe how these principles are reinscribed in other spatial arrangements throughout modernity. This is not a matter of establishing a linear genealogy or attributing to the plantation the status of a universal origin, but of understanding how certain historical rationalities are rearticulated under new mediations.

The Plantation, Modernity, and Racial Terror

It is at this point that dialogue with analyses that interrogate the city through its imperial inscription becomes analytically productive. Examining the contemporary city as a space of reinscription of imperial practices, Ida Danewid argues that so-called “global cities” do not represent a rupture with the colonial past, but rather the reconfiguration of a durable imperial rationality (Danewid 2020). Techniques of territorial segregation, institutional abandonment, and differential exposure to violence do not return to metropolitan centers as intact inheritances, but are rearticulated through urban policies, security regimes, and neoliberal dispositifs of spatial management.

The argument developed in this essay departs from a different, yet convergent, point of departure. By situating the colonial plantation as an exemplary historical configuration, it seeks to understand how principles of differential administration of life—intensified there—are later rearticulated by capitalist urbanization. If, in Danewid’s analysis, the global city appears as a late urban form of empire, here the plantation is understood as one of the contexts in which rationalities traversing different temporalities and scales become particularly visible. The affinity between these approaches lies in the recognition that the production of space operates as a central technology of racial capitalism.

Within the plantation, the organization of space involves the elaboration of economic models, classifications, norms, and practices that naturalize violence and render it an integral part of everyday life. Physical coercion, exemplary punishment, and permanent threat organize conduct and secure productivity. It is in this register that racial terror can be understood as an analytical category. Racial terror designates a historically structured regime of violence administration, in which differential exposure to suffering, precarity, and death becomes constitutive of spatial production. It does not reduce to extreme events but operates as a technique of governance incorporated into spatial, juridical, and economic practices that regulate labor, mobility, and permanence in territory.

Rearticulation of Imperial Practices in Contemporary Cities

As capitalist relations generalize across space, regimes of violence and differentiation that had operated in concentrated form within specific contexts are rearticulated under new historical mediations. Urbanization does not reproduce the spatial forms of the plantation, but reorganizes principles present in different colonial and imperial experiences—such as the differential administration of life, the production of disposable territories, and the naturalization of exposure to violence—within distinct urban registers. Housing policies that engineer segregation through market mechanisms or state neglect, regimes of territorial control that militarize certain neighborhoods while protecting others, and unequal access to circulation and institutional protection become central mechanisms through which these rationalities are inscribed in urban space. To cite brief examples: the logic of containment and exposure finds resonance in the policing of favelas in Brazil, the management of racialized banlieues in France, or the foreclosure crises that disproportionately devastated Black neighborhoods in the United States. Violence is not transferred intact from one context to another; it is transformed, redistributed, and updated according to the historical requirements of capitalist accumulation and life governance.

Finally, Fanon’s reading of the colonial city offers a decisive key for understanding this persistence. By describing the compartmentalized city—divided between the settler’s zone and the colonized’s zone—Frantz Fanon reveals a radical spatialization in which the separation between protection and exposure, abundance and deprivation, life and death is materially inscribed in territory (Fanon 2022). This organization does not constitute a historical anomaly, but an ordering principle that traverses modernity, assuming distinct forms according to context.

Concluding Remarks

This essay has argued for understanding the colonial plantation not merely as a historical antecedent, but as a key analytical prism for deciphering the logic of modern spatial production. The plantation constitutes a socio-territorial form that inaugurates a specific mode of managing bodies—through racialization, extreme extraction, and the administration of terror—whose fundamental principles are deflagrated and rearticulated throughout modernity. By placing plantation, colonial city, and contemporary urbanization in relation, the analysis proposes racial terror as an organizing principle that links these formations within a shared imperial rationality. The conceptual displacement effected here—dissolving the analytical separation between colony and metropolis through the category of the urban—allows us to trace the continuities in the experience of racialization, expropriation, and differential exposure to violence.

The primary limitation of this theoretical exercise lies in its high level of abstraction. While it constructs a conceptual framework for tracing a logic, it does not offer sustained empirical analysis of any specific contemporary urban context. The examples invoked are illustrative, not exhaustive, and the argument would benefit from future research that applies this framework to concrete historical and geographical cases. Such studies could investigate, for instance, how the plantation logic mutates in post-colonial urban planning or in the governance of migrant enclaves in global cities.

Ultimately, this perspective challenges us to view the urban not as a neutral or progressive space, but as a field constitutively traversed by enduring racial hierarchies. The urbanization of empire, therefore, is not a concluded chapter but an ongoing process, demanding analytical tools capable of identifying the spectral persistence of the plantation in the very heart of the modern metropolis

Danewid, Ida. 2020. “The Fire This Time: Grenfell, Racial Capitalism and the Urbanisation of Empire.” European Journal of International Relations 26 (1): 289–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066119858384.

Fanon, Frantz. 2022. Os condenados da terra. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar.

Fitzpatrick, Peter. 2007. A mitologia na Lei Moderna. Porto Alegre: Editora Unisinos.

Lefebvre, Henri. 2019 [1970].” Da cidade à sociedade urbana”. In A Revolução Urbana, 2° ed. Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG.

Monte-Mór, Roberto Luís. 2006. O que é o urbano no mundo contemporâneo. Belo Horizonte: UFMG / Cedeplar.