Public Imagination: The Challenge of Populist and Authoritarian Politics

archive

Public Imagination: The Challenge of Populist and Authoritarian Politics

global-e has been running a series of postings about the populist backlash against globalization in many societies around the world. This trend has been marked by resurgent rightwing nationalism and, in many cases, authoritarianism. Our purpose in initiating this new, related series of contributions is, above all, to liberate public imagination from largely nationalist frames of reference that have fueled the rise of ultra-nationalist populisms in such countries as Russia, India, Turkey, Hungary, Egypt, Philippines, and now the United States. The Brexit vote and the rise of right wing parties in Europe point to a similar backlash against globalizing tendencies, although this brand of populism is in large part distinguished by fervent opposition to foreign policies that have generated menacing transnational migrations of people fleeing war-torn combat zones.

This regressive trend visible throughout the world signals what may be an epoch-defining abandonment of the post-1945 commitment to democratic forms of governance and advocacy of human rights. It demands in response that public engagement flourishes in modes of consciousness that transcend the national, styles of political agency committed to overcoming challenges facing humanity in common while fighting to transform specific local and national struggles.

Today’s regressive politics are partly due to deficiencies of public discourse and lapses in the political and moral imagination of dominant social classes. Right-wing populism and nativism warn us that more primitive, chauvinist forms of collective political imagination are asserting themselves over what now appears to have been a vanishing veneer of tolerance and political civility. The widespread lack of trust in government and governance is being intensified by disinformation, fake news, and corporatized media that have eroded allegiances among the citizenry and engendered savage attacks on traditional elites.

There are several systemic and structural factors that seem relevant when interpreting present trends. In part, the backlash against liberal modes of ‘political correctness’ seems driven by a growing belief among peoples around the world that neoliberal economic globalization is both unfair to ordinary people and undermines traditional identities based on nationhood and ethnicity. Growing global inequality is a direct expression of these tendencies, whose impact on individual lives is manifested in political and social destabilization, compromised national autonomy, and feelings of diminished self-determination in many spheres of private and public life.

Furthermore, the collapse of the Soviet Union seems to have contributed to the present malaise. The loss of the binary geopolitical and ideological “other” co-determining global order in the second half of the 20th century, and the triumphalist Western response to that collapse, fed ambitions of global domination and shifted capitalism from its more compassionate Keynesian compass, inducing instead the adoption of predatory forms of economic policy. Gone are the days when foreign aid, development, and the competition for “hearts and minds” mattered. No matter how uneven the outcomes, such policies signaled an affirmation of global welfare that no longer obtain. Capitalism unchallenged by socialism veers toward extremes, aggravates inequalities, and induces acute forms of alienation and social despair throughout civil society.

Despite backlash against increasingly problematic global interconnectivities and their societal effects, public imagination needs to move beyond the narrow realm of national interests in order to respond to global realities...

The present global atmosphere is unusual—disturbed by what exists, yet lacking any sense of a feasible alternative that extends the social democratic ethos of the West into the future. When this gap between feasibility and necessity becomes too burdensome for societies, demagogic leaders emerge who encourage denial, escapism, and extremism. Such appeals are attractive to outraged and frightened citizens. It is this sort of moral and political vacuum that Donald Trump is filling for many Americans who want enemies to blame, lethal promises to keep, and above all, entertaining spectacles to divert their attention from the complex and difficult challenges confronting humanity. “Trumpism,” now manifest in diverse national forms, seems on track to capture global governance having gained control of several key national governments.

To a considerable degree, right wing populism is a response to the failures of political, economic, and cultural systems to uphold the material and psycho-political wellbeing of their respective national populations. Yet despite backlash against increasingly problematic global interconnectivities and their societal effects, public imagination needs to move beyond the narrow realm of national interests in order to respond to global realities and challenges cognizant of all dimensions of civilizational identity, sustainability, humane values, and security. The revitalizing of public discourse to illuminate and transform present global tendencies is a matter of societal, and indeed, civilizational urgency, perhaps even survival.

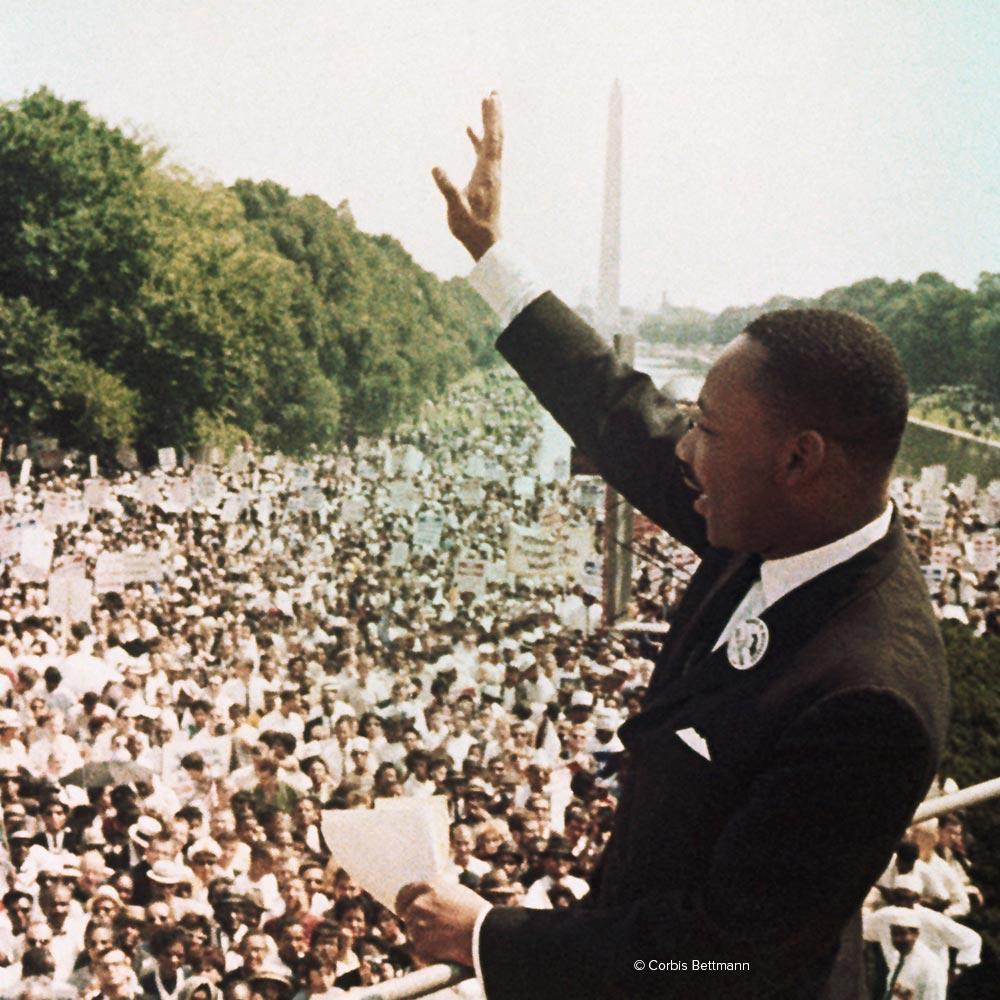

Image credit: Corbis Bettmann.

Thinking about public imagination

Against this background, we hope to stimulate culturally and historically informed reflection on moral/ethical imagination across borders of countries, civilizations, religions, and other relevant sources of identity. Public imagination as diversely manifested is closely linked with the institutions and activities of public spheres. It is engaged and shaped through cultural and religious traditions and societal norms, informal and formal politics, and diverse forms of print and electronic media. In these contexts today the channels, mechanisms, and arenas in and through which public imagination characteristically functions are being dangerously narrowed not just by demagoguery, nativist and xenophobic discourses, and moral absolutism, but also by the increasing dominance of elite interests, monetary manipulations, and media passivity in these spaces. Humane consensual political life cannot flourish in such an atmosphere.

A plurally conceived ‘public imagination’ suggests connectivities across a cluster of interrelated ideas: a public sphere or spheres, counter-publics, public opinion, public interest, public reasoning, public space, social and spiritual imaginaries. Addressing such subject matter inevitably deals with contested domains of societal life, not least secularist worldviews. If “public” imagination is considered to be active in all societies, then its specific contours vary widely and depend on particular historical, cultural, political, religious, institutional and local configurations that must be reckoned with. For these reasons its role in shaping governance and policy also varies considerably. The idea of public imagination(s) encompass a variety of perspectives—philosophical, psychological, historical, affective, normative, spiritual, performative—and can be thought of as the outcome of the interplay between public and private imaginaries. We are faced with the distressing question as to whether closures of public imagination can be surmounted in political spaces that are becoming more and more intolerant toward diversity and differences. To what extent are capacities of public imagination foreshortened by this populist tsunami? Or alternatively, can these developments give rise to a dialectical set of responses in which imaginative visions, strategies, and tactics are articulated to discover or enlarge pathways to humane futures?

The term ‘public imagination’ is acknowledged to be unstable, problematic if conceived monolithically, burdened by definitional, sociological, and epistemological difficulties. These include the fact that the concept of imagination as a cognitive faculty bears a long history of Western rationalist, positivist, and Romantic biases. Nevertheless, throughout the post-WWII period there are increasing recognitions of the utility of orienting inquiry around collective forms of imagination. For example, the work of Benedict Anderson, Arjun Appadurai, Donna Haraway, and Charles Taylor are indicative of this reliance on social imaginaries to interpret modern conditions. Media studies are an increasingly important resource for such investigation given the ascendance of knowledge mediation through images and the sheer ubiquity of images in a media saturated, post-Internet, digitally supercharged world in which images are viral and more of reality is becoming virtual. The imagination of cultural selves with or against cultural ‘others’ is being globaly exploited by mainstream media for the sake of spectacle, generating one of the constitutive features of the contemporary world.

Imagining an agenda

These phenomena encompass a wide range of vital concerns that suggest critical, aesthetic, practical and policy-oriented responses, since investigations into the failures of government policy by reference to the weakness or bias of public imagination help to explain (for example) the disappointing national and global policy responses to threats posed by climate change and the continued possession of nuclear weapons. In this respect, a multiperspectival initiative concerned with the disappointing inability of public imagination to grasp the biopolitical historical moment, and redirect energies and attention to the currently deficient protection of human and planetary interests, is urgently called for.

We hope to stimulate culturally and historically informed reflection on moral/ethical imagination across borders of countries, civilizations, religions, and other relevant sources of identity.

An engagement with public imagination in the context of 21st-century global challenges might select a few initial priorities: 1) analyzing how to address the global and human interest in a world of sovereign states whose governments are focused on national concerns and interests, too often through either populist or elitist optics, short-term electoral cycles, special interests, and maintenance of the status quo; 2) assessing concerns of transnational and global scope, such as nuclear weapons, climate change, food security, health, economic inequality, migration, human trafficking, terror & crime networks; 3) enlarging the spheres of policy debate in democratic societies to envision alternatives that explore nonviolent paths to achieving both national and human security.

The foregoing examples underscore the need for research on the theoretical and practical dimensions of public imagination(s) toward improving discourse and policy on threats confronting the nation, the world, and humanity. Processes of public reasoning and persuasion as conditioned by particularities of time and place, the status of the ‘public’ and distinct ‘publics,’ the limits, dangers, and potentials of imagination as a politically salient and policy-relevant variable given the challenges of the 21st century, orient the explorations and conversations across borders that we are hoping to stimulate within a heterogenous community of global scholars, thinkers, and activists sharing our concerns, as well as our faith in the relevance of commentary, passion, conscience, and dialogue.

Image Credits

Top image: man ‘flying’, Japan.

Image credit: Natxo Bassols photography, “Time Up”

http://natxobassols.com/portfolio/time-up/tokyo/

mounted police, "Chilean Winter" education reform protests, Santiago, Chile, 2011.

Image credit: Tommaso Durante, The Visual Archive Project of the Global Imaginary.

Martin Luther King, Jr., Washington D.C., August 1963.

Image credit: Corbis Bettmann.

Occupy D.C. camp, McPherson Square. Washington, D.C. 2012.

Image credit: Tommaso Durante, The Visual Archive Project of the Global Imaginary.

woman ‘flying’, India.

Image credit: Natxo Bassols photography, “Time Up”

http://natxobassols.com/portfolio/time-up/india/

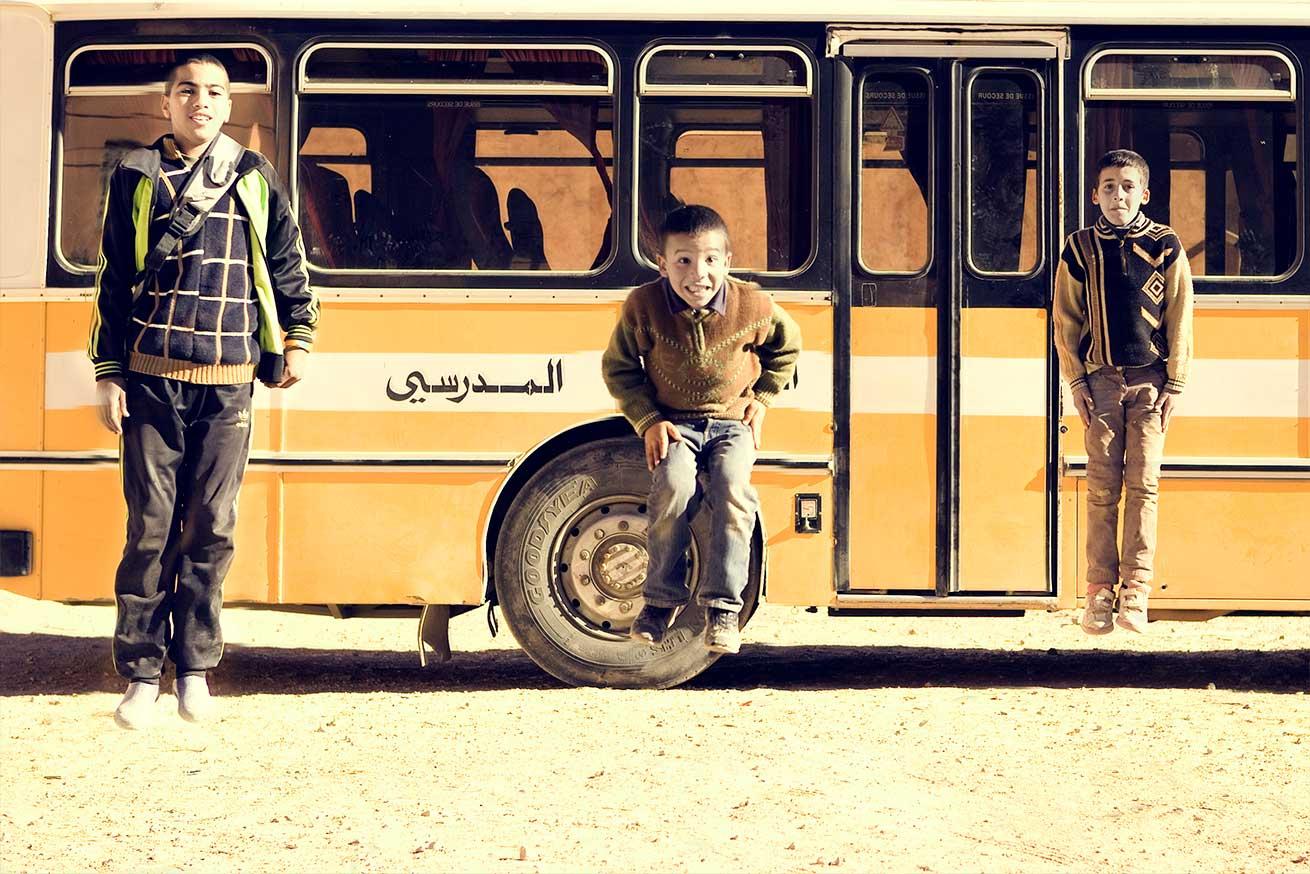

boys ‘flying’, Marracesh, Morocco.

Image credit: Natxo Bassols photography, “Time Up”

http://natxobassols.com/portfolio/time-up/marrakech/

Archive page: Occupy D.C. camp, McPherson Square. Washington, D.C. 2012.

Image credit: Tommaso Durante, The Visual Archive Project of the Global Imaginary.