Why China Envies Russia's Media

archive

Why China Envies Russia's Media

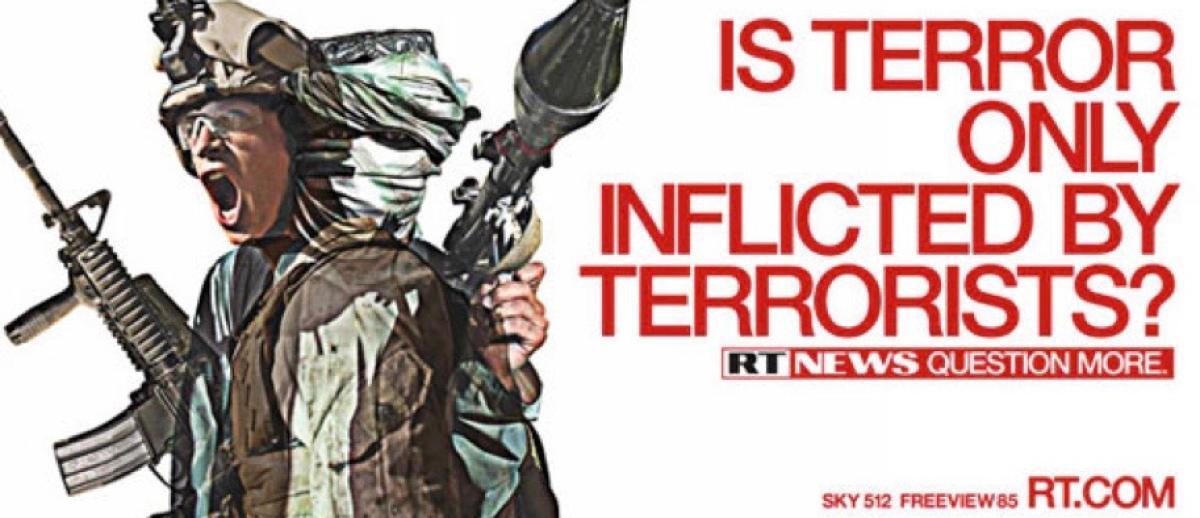

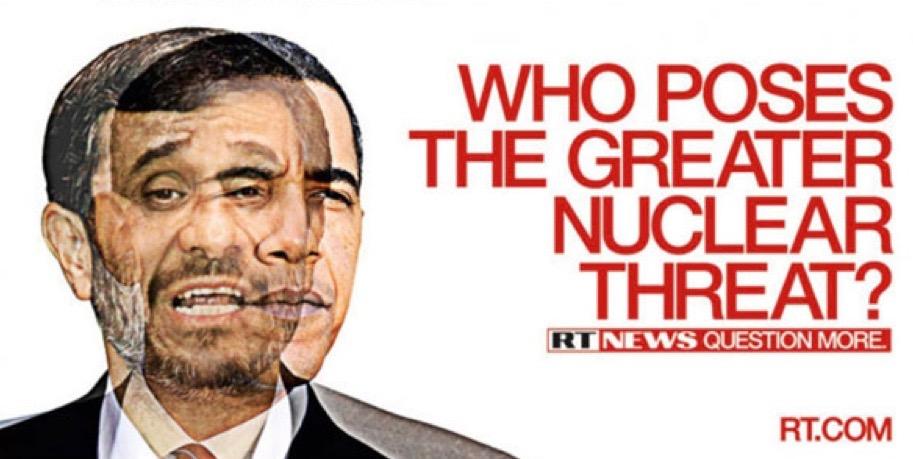

In the wake of Brexit and the recent revelations on Russia’s role in the U.S. election, talk intensified among politicians and analysts in the West about the influence of Russian media. Beyond hacking and fake news stories spread online, Russia Today (RT), the satellite television targeting viewers around the world, is being recognized as an effective weapon in what Western critics see as a deliberate disinformation campaign by the Russian government intended to sow distrust among European and North American viewers towards their political systems. RT’s YouTube channel advertises itself as the “most watched news network on YouTube: over 4 billion views.” The argument goes that RT is so good at presenting conspiracy theories as legitimate alternative views on world events—such as that it was the Ukrainian army that shot down the Malaysian Airlines Flight 17 in 2014—that, while they might not believe these versions fully, they come to see mainstream Western media as biased and one-sided. It has also successfully engaged in character assassinations of unfriendly Western politicians and Russian exiles. Some EU politicians have called for coordinated campaigns to debunk Russian stories in Eastern European media. At one point, RT’s British bank account was frozen. Ultimately, however, some fear that the EU might end up as the weaker party in an information war.

Reportedly, the Chinese government envies RT’s ability to shape international opinion and to instill fear in its opponents. Usually, for Chinese officials, Russia is a cautionary tale of China’s erstwhile Big Brother that has now been brought down and humiliated. Thus they marvel at the fear Russia’s media has generated in Europe. By comparison, the Chinese government’s efforts to present an “alternative voice,” primarily through the satellite network CCTV, have yet to be taken seriously. Despite China’s far greater success in building up political and economic power, opponents of liberal democracy worldwide look to Russia, not China.

The Chinese government has spent a lot of money, probably much more than Russia—the precise amount cannot be verified, but one oft-quoted figure is $5.5bn—on promoting the overseas expansion of China’s state media, especially in English. The justification for this has been very similar to that behind RT’s global operations: to strengthen “China’s voice” in a global news coverage seen as monopolized by the West and expand its geographical footprint, not just in Europe but also Africa and Asia. At a time when Western media’s foreign networks have been shrinking, those of China’s Xinhua News Agency, People’s Daily, and CCTV have been expanding rapidly, and English-language news production, from print to broadcast to online, has ballooned. Yet, there are few indicators that foreigners actually read or watch. By and large, these networks are still seen as mere propaganda outlets, while RT, with much less funding, has garnered some credibility as an actual alternative to CNN or BBC.

Why is this? For one thing, CCTV has not been able to attract media personalities of the stature of Larry King or Ed Schultz, who now host shows on RT. For another, it has not come close either to the provocative content of RT’s reporting nor to the lively format of its studio talk shows. According to a Chinese journalist who has worked for an RT subsidiary, RT’s advantage is not better reporting or technology but a more flexible operation and a young staff (the editor-in-chief, Margarita Simonyan, is 36) that is attuned to the interests, tastes, and language of younger Western audiences and apt at using social media. RT’s popularity rides the same wave of discontent that has benefited “alt-right” American websites such as Breitbart News. In contrast, CCTV and other Chinese media are hobbled by many layers of editors and bureaucrats, averse to any risk of antagonizing Communist Party officials. Provocative content that strays too far from the foreign ministry’s position would land editors in trouble: this encourages caution and self-censorship. Besides, compared to their Russian counterparts, Chinese journalists tend to have less familiarity with foreign countries and weaker social networks abroad. This is both because of budget and regulatory restrictions and because most see foreign postings as only a stepping stone towards promotion back in China. The more ambitious or colorful tend to quit foreign correspondence in disappointment, turn their energies from news reporting to explicating the “Chinese position,” or adopt a blander style and blend in.

RT’s popularity rides the same wave of discontent that has benefited “alt-right” American websites such as Breitbart News.

So, counterintuitively, one reason CCTV is less successful as a propaganda tool is that it is less outrageous than RT. But, to be fair, neither Russian nor Chinese media abroad can be reduced to its propaganda function. Although they have yet to convey a “Chinese angle” on world news to foreign audiences, Chinese journalists are in a position to provide people in China with unprecedented access to first-hand accounts to the world at a crucial time of increased global engagement. Many of them, whether they identify with the official vision of fighting against Western media hegemony or make fun of it, take this role seriously. Yet censorship, a perceived lack of domestic interest in in-depth stories, incomplete familiarity with foreign societies, and organizational shortcomings combine to dampen the impact of their reporting. So far, China’s global media presence has far less to show for its money than that of its more modest Russian counterpart.

The author's book, Reporting for China: How Chinese Correspondents Work with the World (2017), is available from the University of Washington Press.