Art voyages: Rethinking biennales with Vasco Da Gama

archive

Art voyages: Rethinking biennales with Vasco Da Gama

“The Arrival of Vasco da Gama” by the widely-exhibited artist Pushpamala N. (Image 1) is a carefully choreographed re-enactment of an 1898 oil painting by José Veloso Salgado (Vasco Da Gama perante o Zamorin). In the original, Salgado portrayed an imperious Da Gama before an orientalized Zamorin (local king) and his court. The encounter, which took place in 1498 in Calicut, South India, was a prelude to Europe’s multiple colonial enterprises.

Salgado’s painting landed him a win in a contest on the occasion of centenary celebrations to mark the ‘discovery of India’ held in 1898.1 But even centuries before the painting was unveiled, Da Gama’s stature as a leading figure in the Western narrative of globalization had begun to emerge. As Sanjay Subrahmanyam has argued, da Gama’s legend “began in his own lifetime, and… he participated in it.”2 Iconography has been central to the creation of this legend.3 By intervening in this legend and its iconography through the technique of personification which has been at the core of Pushpamala N’s oeuvre, she “turns Salgado’s conception on its head, returning what is a work of imagination that has over time gained a degree of historical legitimacy, to the space of fiction and masquerade.”4

Pushpamala N’s “The Arrival of Vasco da Gama” was the centerpiece of an installation at the second edition of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale (KMB) in 2014.5 The installation was placed in Aspinwall House—originally a large multipurpose building in the southern Indian city of Kochi, named after a Britisher who employed it as business premises in the 19th century. That is, the vestiges of one empire nested in the vestiges of another.

Image 2. Aspinwall House, Kochi.

The KMB takes place not far from Calicut (Kozhikode) where the historical encounter occurred, and is embedded in the city of Kochi where Vasco Da Gama died.6 Together with the artist’s identity, the place and space of display and the installation’s subject matter shape the political valence of the work itself—though they do not confer political valence merely by virtue of their alignment.7

However, within the realm of large-scale exhibitions such as biennales (including the KMB itself), the above-mentioned proximities are usually an absence rather than a necessary feature. Although these exhibitions spur the creation of artworks that draw heavily on local realities, especially from the Global South, and produce the conditions for their visibility, they nevertheless contribute to undoing some proximities and they re-route identities and subject matter towards a multitude of geographical locations. Against this backdrop, artworks commissioned for biennales in very diverse settings often travel to other events where and through which they might acquire altogether different dimensions in the eyes of their audiences. One could imagine, for example, in addition to the journeys this artwork has already made, how Pushpamala N.’s Vasco Da Gama would be received in Portugal or in a Portuguese former colony—also in consideration of the fact that this figure and his legacy have long engendered mixed reactions.8

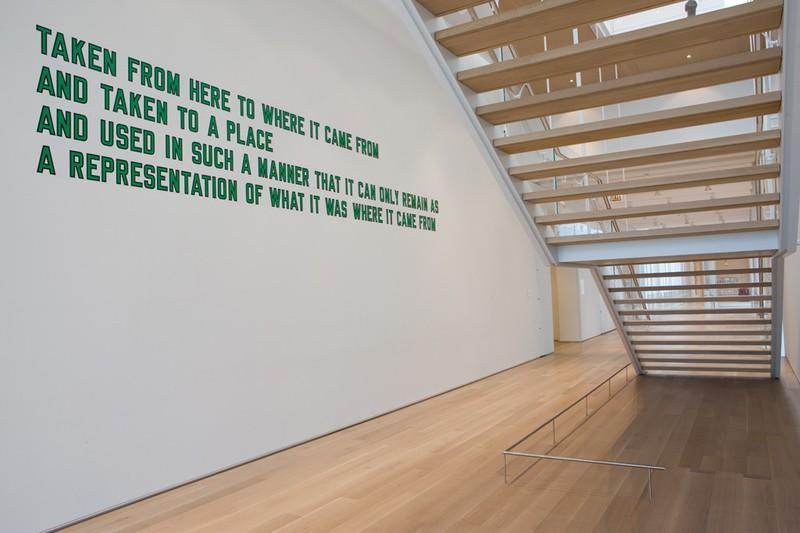

Image 3. Lawrence Wiener, "TAKEN FROM HERE TO WHERE IT CAME FROM AND TAKEN TO A PLACE AND USED IN SUCH A MANNER THAT IT CAN ONLY REMAIN AS A REPRESENTATION OF WHAT IT WAS WHERE IT CAME FROM" 1980. Source: Art Institute of Chicago

Artworks regularly circulate across art world locations, and the biennale cultural form does too, the KMB being one of its latest incarnations. This form has proliferated all over the world since the first Venice Biennale in 1895, hence the two phenomena thrive symbiotically. The biennale circuit involves diverse institutions—and their iterations take on different formats each time—despite all being subsumed under the same cultural category. To attend to the question of difference posited by cultural forms within the art world (museums, biennales, art fairs, galleries etc), I have elsewhere suggested three interlocked analytical directions: the first delves into the specific nature of the form being circulated, re-embedded, or territorialized; the second focuses on issues of temporality, that is, the reason for a cultural form’s pace of circulation, the historical contextualization and production of the ‘new’ following the emplacement of an art institution in a given location; and the third explores the issue of place: how a place shapes the life of a cultural form/art institution.9

artworks commissioned for biennales in very diverse settings often travel to other events where and through which they might acquire altogether different dimensions in the eyes of their audiences.

If one looked at the KMB through this prism, one would begin to see that during its short life span, this biennale—started in 2012 as a government initiative that turned into a public-private venture—has acted as soft and fertile ground for asking large questions about the past, history-making, cartography, astronomy, mathematics, culture, the caste system, and old and new empires, among others. In other words, the biennale has begun to ask ontological questions of the surrounding region and beyond, and many Indian and international artists have been called upon to address these questions. The physical spaces of the KMB biennale, in particular the evocative venues deployed for its first three iterations like the one under discussion above, have greatly contributed to the success and popularity of this art institution, and testify to the transformative power of place, space, and the built environment on the artworks on display and vice versa.10 In this respect, the question of the relation between the cultural form and its contents at the KMB has been complicated by the very visual and material potency of everything else on display besides the artworks: the built environment, the natural surroundings, etc.

Yet narratives of circulation in the art world, the diffusion of the “global contemporary,” and the emphasis on circuits of art fairs, biennales, and other recurrent large exhibitions have obfuscated the ways in which place, space, and the built environment intervene in the co-constitution of people and objects—be they artists and artworks or the latter and their audiences. These dynamics are rarely researched and theorized as integral to the co-constitution of people and objects along the routes where they might be encountered. Hence, the existence of quasi-universal settings underpinning such cultural encounters are often implicitly posited. What is more, the inquiry has hardly traveled in the opposite direction to ask how the co-constitution of people and objects speaks back to such settings. In a companion essay (to be published later in global-e) I reflect on some aspects of these interlocked dynamics by placing in conversation the re-representation of Vasco Da Gama at the KMB biennale discussed above, with instances derived from the recently concluded Whitney Biennale in New York and documenta 14 Athens. At these institutions, the emerging assemblages made of artists, artworks, and audiences as well as the places, spaces, and built environment have converged to significantly complicate circulation narratives and, interestingly, have reclaimed some of the proximities highlighted in Pushpamala N.’s “The Arrival of Vasco Da Gama.”

“The Arrival of Vasco da Gama,” by artist Pushpamala N., 2014.

1 http://www.museuartecontemporanea.pt/pt/artistas/ver/42/artists.

2 1997, p. 361

3 ibid., p. 357

4 http://www.pushpamala.com/projects/the-arrival-of-vasco-da-gama/.

5 My research on the KMB is part of my project under the Framing the

6 Vasco da Gama also ‘lives on’ in Kochi’s topography: a square is named

7 It should be noted that this artist is from South India but not from Kerala, and the

class and religious community should be acknowledged here. Moreover, within

this edition of the KMB, non-Indian artists also represented Vasco Da Gama,

raising altogether different concerns.

8 see Subrahmanyam ibid. p. 367

9 Ciotti 2014, pp. 59-61

10 see Ciotti n.d.

Ciotti M. 2014. "Art institutions as global forms in India and beyond: Cultural production,

Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 51-66.

_____ n.d. "Re-making the contemporary: The art-architecture-archeology-heritage complex

Pratt M.L. 2008. Imperial eyes. Travel writing and transculturation. London and New York:

Subrahmanyam S. 1997. The legend and career of Vasco Da Gama. Cambridge: Cambridge