This is What Democracy Looks Like: 21st Century Elections in Mexico and Beyond

archive

Mexican President-elect Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador at voting station, 2018. Photo credit: Carlos Tischler/Getty Images

This is What Democracy Looks Like: 21st Century Elections in Mexico and Beyond

A new phase of globalization has been emerging in recent years, marked in part by a resurgence in the role of national political institutions and processes with contradictory effects on democracy. The modes and consequences of greater citizen control over globalization through national political processes vary from neo-liberal electoralism to exclusionary populist nationalism to the emergence of progressive coalitions that seek to balance global integration with local control. In Latin America, Brazil has seen a distorted extra-electoral transition through the impeachment of Dilma Roussef, while Colombia maintains democratic processes but has also regressed in its security and social policies. Both countries struggle to resolve the contradictions between the social mobilization of liberal politics and the inequality and violence associated with neo-liberal economics. Worldwide, reactionary nationalism and elected authoritarians responding to global challenges of economy and identity are coming to dominate Russia, Eastern Europe, Turkey—and now also Italy. Popular socialist experiments in Venezuela and Nicaragua have hardened into anti-institutional and corrupt authoritarian nationalisms that eschew democracy in the name of justice, and achieve neither.

But another kind of democratic opening is visible in Mexico and Spain. In Mexico, the emergence of a progressive populist, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, has been coupled with greater civic participation (especially among women, youth, and marginalized people) and the strengthening of democratic institutions. Former Mexico City mayor López Obrador’s program of anti-corruption, increased social services, and greater government accountability reads like a Global South version of Spain’s recent no-confidence vote that ousted neo-liberal Mariano Rajoy in favor of a Socialist-led coalition, and this path may prove the best way to deepen self-determination in the 21st century global order. The landmark victory of López Obrador and the MORENA party coalition for the presidency, congress, and most governorships in Mexico delivered a mandate for a deeply democratic response to globalization. As the three-time candidate and virtual winner put it in his first address to the nation: “We will seek profound change...but always in the framework of the law….We will defend the interests of the entire nation—and the best way to do that is to defend the interests of the poor….We will seek relations of peace and friendship with all nations, and mutual respect for self-determination.”

In Mexico, we see a genuine national alternative to global challenges. It is marked by the rise of the MORENA social movement that evolved into the political party coalition that has swept the 2018 elections. Mexico shares with its neighbors decades of distorted economic globalization and a chronic security crisis linked to drug trafficking that has taken over 100,000 lives. Moreover, it suffers from the disruptive impact of U.S. migration policy, which brings in its wake a surge in human rights abuses of Mexican citizens and transient Central Americans alike. A group of Mexican scholars from El Colegio de México have traced the consequences of distorted economic globalization since 2000 through accumulated disadvantages as measured by inequalities in income, social mobility, education, and labor opportunities that now intersect with environmental risks and immigration influxes that are especially detrimental to women, indigenous populations, and those inhabiting rural areas.

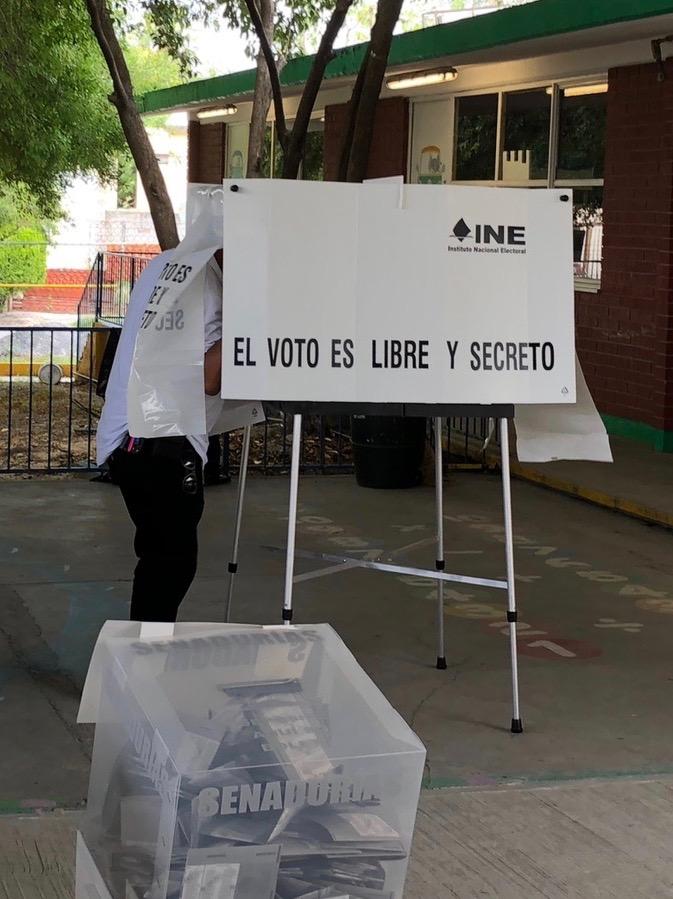

Voting station in Mexico, 2018. Photo credit: Alison Brysk

Yet a generation of legal reforms and the resilience of Mexico’s civil society have fostered a surprising level of mobilization and representation of formerly marginalized interests. Mexico has come far in the last hundred years: from the longest epoch of one-party rule in the twentieth century, through the 1988 opening of electoral competition and the resulting bipartisan system (PRI-PAN) gaining more and more popularity, followed by the 1994 alt-globalization indigenous uprising and now moving into the 21st century with the emergence of independent parties and grassroots movements characterized by a rise in popularity of leftist parties (first the PRD and now MORENA). In 2014, electoral reform established the legal framework for independent candidates, restructured the National Electoral Institute, and opened up legislative posts for re-election. The reform allows for coalition governments and the possibility of annulling a presidential election if certain rule violations affect the outcome of the election (based on the 2006 contested elections where current front runner López Obrador ended up in second place with small margins under questionable circumstances).

The 2018 election was Mexico’s largest election ever, with the Presidency, Congress, plus major offices at issue in 30 out of 32 states—over 4,000 political offices contested nationwide. It was also the most inclusive electorate: 89 million Mexicans out of 137 million citizens registered and over two-thirds voted. More than a quarter of registered voters were 18-19 years old, and a system of additional non-territorial polling places was set up to accommodate voters unable to visit their district of origin. Political parties were required to present gender-balanced slates of candidates, and 8-10 parties competed in each state: the historic PRI and PAN, and the emerging MORENA; the leftist parties PT and PRD; the evangelical Christian PES; the Green Party; and an array of local and sectoral parties along with independent candidates. As a result, voters flocked to participate in record numbers, which fostered the only systematic shortfall noted by observers: the special polling places scattered across the states ran out of ballots by noon on Election Day. This led to a number of vigorous but peaceful citizen demonstrations at Electoral Commission offices. Nevertheless it’s estimated that this shortcoming only affected a small proportion of potential voters at the national level.

The landmark victory of López Obrador and the MORENA party coalition for the presidency, congress, and most governorships in Mexico delivered a mandate for a deeply democratic response to globalization.

The Mexican election was rigorously monitored by the autonomous National Electoral Institute, backed by state-level Electoral Commissions and the Electoral Tribunal from the judicial branch of the government. Despite concerns due to budget cuts in the Secretary of State’s Fund for Supporting Electoral Observation, hundreds of international and civil society observers throughout the country were matched by a designated presence of an average 10-12 political party representatives monitoring the vote at each polling place. For the first time, Mexico employed state of the art procedures to prevent fraud via ballot boxes that were literally transparent, with each one sealed and subjected to “chain of custody” tracking. Secure digital vote counting systems were firewalled and matched by independent exit polls and a carefully designed representative “quick count.” Moreover, a special hotline was established to report vote-buying, and the sale of alcohol was banned throughout the country for 48 hours during the electoral period. Electoral commissions, ballot repositories, and polling places were guarded by soldiers and police.

Monitoring Mexican election results, 2018. Photo credit: Alison Brysk

The protection of ballots unfortunately did not extend to candidates, as Mexico’s most democratic election was also its most violent, with over 130 election-related assassinations throughout the country. The violence mostly targeted local candidates in the poorer, most conflictual states such as Guerrero and Chiapas. It is an ironic testament to the legitimacy of the national process that regional thugs who are no longer able to control local government by fraud have turned to physically eliminating the competition, which raises concerns about the “Colombianization” of Mexican politics and regional inequality with respect to security and citizenship. For example, the Puebla gubernatorial election is currently contested due to violence, ballot stealing, and fraud.

The real winner of Mexico’s election was citizenship—and the test will be whether this mobilization and civic solidarity can be sustained. Engaged citizens have bolstered the public sphere through civic movements, including a campaign against fake news called VerificadoMX, a youth-led digital platform to fact-check every candidate’s statements during the debates and throughout their campaigns. Cross-cutting popular identities have both fortified and complicated the leftist project, which still faces opposition by a large middle and upper class population who falsely fear that the triumph of MORENA may harbor the phantom of Venezuelan populism. But this comparison by the Mexican and international elite fails to consider the difference in political experience, role of the military, and economic interdependence between Mexico and other Latin American populisms with more authoritarian tendencies—a concern explicitly addressed by López Obrador in his victory speech.

The real winner of Mexico’s election was citizenship—and the test will be whether this mobilization and civic solidarity can be sustained.

Voters at polling station in Mexico, 2018. Photo credit: Alison Brysk

Similarly, López Obrador’s alliance with the Evangelical Party stoked fears of regression on LGBT+ rights that were a hallmark of his leadership of Mexico City. However, the LGBTTTI+ agenda in Mexico has proven resilient through this electoral cycle, as a newly formed LGBTTTI+ National Coalition (which includes 192 activists from NGOs, academic institutions, political parties and youth organizations) has pushed for clear statements from all of the candidates on same-sex marriage and adoption, leading to similar questions on abortion and recreational/medicinal use of marijuana. In fact, the new President stated clearly that he would honor both “todas creencias” (all beliefs, i.e. religious minorities such as evangelicals) and, in the same sentence, “todas preferencias sexuales” (all sexual orientations).

This is what democracy looks like: inclusion, representation, rule of law, and self-determination. The question for Mexico is how far this genuine advance in democracy can go to overcome the global and local structures of inequality and insecurity. Mexico’s struggle is a challenge—and perhaps a model—for its neighbors and the worldwide quest for human rights.

'DO NOT SELL YOUR VOTE' -- 2018 Mexican election posters. Photo credit: Alison Brysk