“Us,” “Them,” and the Problem with “Balkanization”

archive

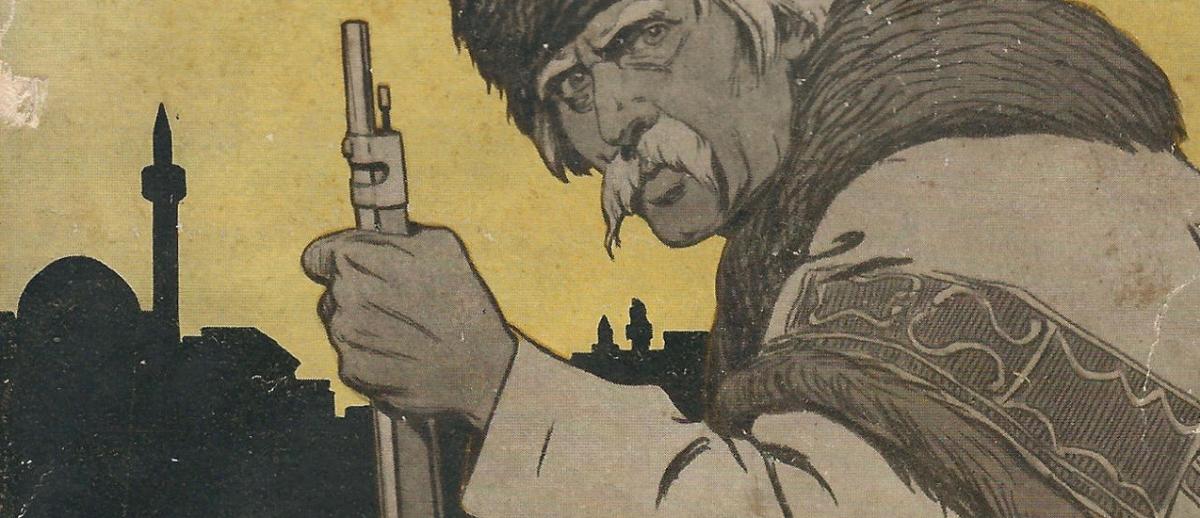

cover illustration of book by German political economist Arthur Dix, Zwischen Beresina und Wardar. Landsturmbriefe und Balkanbilder. 1920

“Us,” “Them,” and the Problem with “Balkanization”

The construction of polarized collective identities accentuates perceived (cultural) differences, thus playing an integral role in shaping how we identify and respond to emerging threats both imagined and real. By homogenizing populations, such constructions create antagonistic and conflict-oriented relationships resistant to resolution. This essay argues that the much used and somewhat fashionable term “balkanization” is itself an example of such essentialism, which upholds a longstanding and prejudicial ‘European’ self-identification over against a Balkan ‘other’ that aggravates discord in the region.

Recognizing the Other

The relationship between other and self is inevitably problematic and complex. Whether a relationship defined by fear, hostility, and struggles for domination, or by independence, political representation, and hospitality, a polarity in the lexis of otherness consistently arises. ‘Sameness’ and ‘difference’ belong to an apparently timeless reflex of social, cultural, and political ‘othering’—a long useful concept and traditional point of intersection between theoretical discourses including post-colonialism, deconstruction, Marxism, and feminism that inform contemporary discussions of the socio-political problems of a rapidly changing and increasingly globalized, yet localized, world. In this context, important questions must be framed: how can we find a way to co-exist with and relate to the other? How can we negotiate cultural identity? How are we to ethically conceive of the other at all? And, how can the encounter with otherness be accurately represented? Are our identities and culture changeable, or they are metaphysical? And are they now always fragmented? The hybridization of cultures is one among diverse processes (globalization, protectionism, nationalism, transnationalism, localization, isolationism, internationalism) that affect our paradigms of “us” and “the others.”

Frederik Barth (1969: 22) the Swedish scholar and researcher of ethnic identities and boundaries, held that what is transferred across time is not the content of any cultural arsenal, but the boundary of a particular group: the inner content changes, while boundaries survive. But ethnic boundaries imply inter-ethnic relations: ethnic identity is formed and survives right through to the contacts with other ethnic groups. Differences between ethnic categories are not explained by the absence of movement, contact, and information, but by understanding social processes of excluding and including.

Many discourses in contemporary politics express a need and sometimes a request for recognition. We may say that the need for recognition is one of the drivers of nationalistic movements, but the demand for recognition in contemporary politics appears in many other forms, especially in the name of minorities and “disadvantaged” groups. Usually, a request for recognition has a quality of “urgency” because of a presumed relationship between recognition and identity. The claim is that our identity is formed partially through recognition. But it is also formed through recognition’s absence, and very often through “false” recognition from others intending to damage, compel submission, or to force other human beings into a distorted and reduced form of existence. (Taylor 1995: 25)

The hybridization of cultures is one among diverse processes... that affect our paradigms of “us” and “the others.”

Nation-states with liberal-democratic social systems have different approaches to managing ethno-cultural heterogeneity and demands for recognition. The problem is that social, political, and other scientific theory largely neglected the realm of ethno-cultural relations until the middle of the 1980s, when a few political philosophers started to deal with the issue of managing of cultural and ethnic diversity. One of the reasons for the delayed interest of scholars and politicians in these issues has been their preoccupation with the myth of so-called “ethno-cultural neutrality.” (Kymlicka 1999: 3)

Some theorists argue that this is precisely what distinguishes liberal 'civic nations' from illiberal 'ethnic nations'. Ethnic nations take the reproduction of a particular ethno-national culture and identity as one of their most important goals. Civic nations, by contrast, are 'neutral' with respect to the ethno-cultural identities of their citizens, and define national membership purely in terms of adherence to certain principles of democracy and justice. For minorities to seek special rights, in this view, is a radical departure from the traditional operation of the liberal state. Therefore, the burden of proof lies with anyone who would wish to endorse such minority rights. (Kymlicka 1999: 8). This is the burden of proof which liberal culturists try to meet with their account of the role of cultural membership in securing freedom and self-respect. They try to show that minority rights supplement, rather than diminish, individual freedom and equality, and help to meet needs which would otherwise go unmet in a state that clings rigidly to ethno-cultural neutrality.

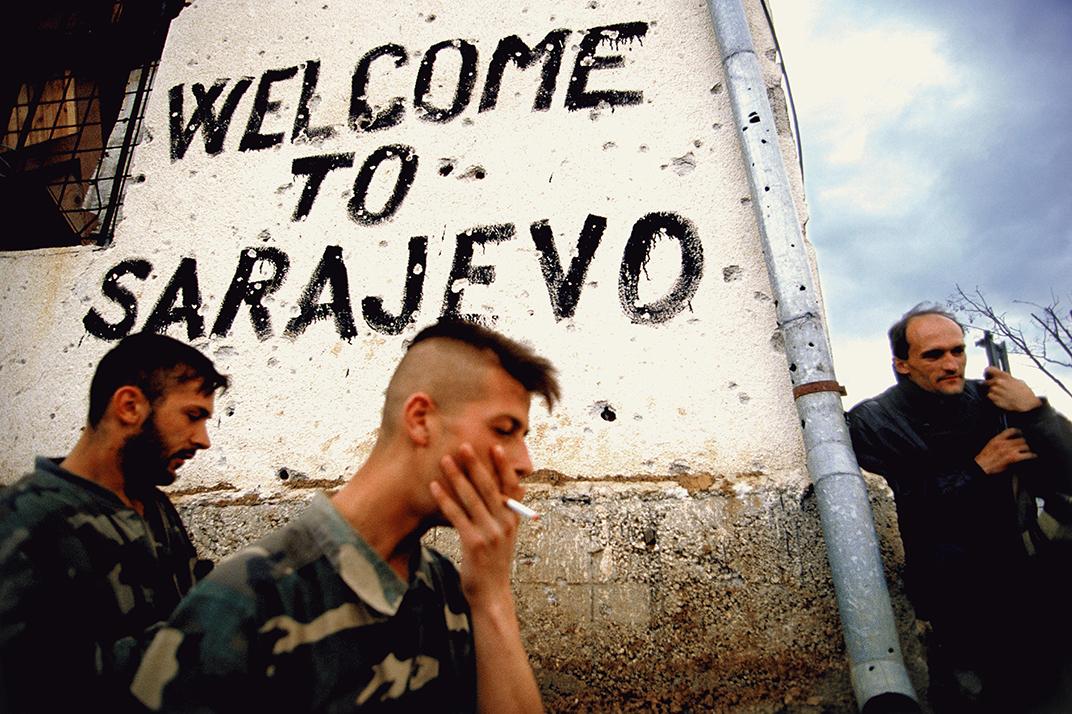

Photo credit: Ron Haviv

Balkanization

In a closely related context of Western perceptions of ‘others’, we may mention the “phenomenon” called “balkanization.” In 1997 a Bulgarian historian and philosopher, Maria Todorova, published Imagining the Balkans, which launched many debates among academic, political, journalist, and other circles. Her study deals with the region's inconsistent (but usually negative) image in Western culture as well as with the paradoxes of cultural reference and its assumptions. In it, she develops a theory of Balkanism or Nesting Balkanisms, similar to Edward Said's “Orientalism” and Milica Bakić-Hayden's “Nesting Orientalism.” Todorova has said of the book: “The central idea of Imagining the Balkans is that there is a discourse, which I term Balkanism, that creates a stereotype of the Balkans, and politics is significantly and organically intertwined with this discourse. When confronted with this idea, people may feel somewhat uneasy, especially on the political scene... One of the prejudices and stereotypes related with Balkans and Balkanisms is the presumed relative innocence of Western Europe, placing responsibility for all accidents and mistakes that happened in Balkans in the 20th century on the Ottoman heritage and Turkey.” (Todorova 1997: 276)

The term “balkanization” was not coined in “the longest century of Empire”1 when Balkan nations were gradually separating from the Ottoman Empire, but instead at the end of World War I, when Albania was added to the map of Balkan nations that were created in the 19th century (Todorova 1997: 46). After the First World War scholars and politicians used the term “balkanization” to denote a process of national fragmentation of former geographical and political units into new problematic national states with disrupted political relations, as in the case of what happened during the Balkan wars. A deeper (and troubling) analysis of “balkanization” was produced in 1921 by Paul Scott Mowrer, the European correspondent of the Chicago Daily News. Analyzing the political situation in Austria, Hungary, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Romania, Yugoslavia and Greece, he concluded that this is a “region of hopelessly mixed races, a collection of small states with more or less backward populations, economically and financially weak, envious, with conspiratorial behaviors, scared, constant victims of manipulations by the great powers, as well as violent outbursts of their own passions.” (Mowrer 1921: 34) The element of foreign involvement in the internal affairs of small states is so aggressive that Michael Foucher in 1994 was motivated to define “balkanization in a literal sense as the constant involvement of foreign powers (Russia, Austro-Hungary, Germany, France and Great Britain) directed at the protection or establishment of their spheres of interests” (Todorova 1997: 49).

Notions ascribed to “the Balkan” reveal the process of making the image of Europe by defining the ‘other’ as Oriental, unpredictable, dangerous, chaotic, dirty, lazy, primitive, cruel, selfish, uncooperative, etc. (Mursic & Jezernik 2007: 7). Yet historical evidence attests instead to the presence of tolerance, cooperation, and hard work among the region’s peoples. The region also characterized by ancient cultures and civilizations, urbanization, classical philosophy, and pre-industrial economic efficiency. For centuries the Balkan Peninsula was almost the only part of Europe with a tradition of tolerance toward people of different religions, ethnic origins, and cultures. Indeed, the peoples of the Balkans lived in a multicultural milieu long before it became fashionable in the West. In 1492, when Sephardic Jews were exiled from Iberian Peninsula by the Catholic Church, the Balkan Peninsula—at that time under the Ottoman Empire—was a tolerant place that welcomed them.

the peoples of the Balkans lived in a multicultural milieu long before it became fashionable in the West.

Conclusion

Even as globalization accelerates trans-global and supra-territorial connections, matrices of prejudice and stereotypes about “the other” from past centuries remain, in old and new forms. This fact is borne out daily in crisis regions where ethnic heterogeneity, migration, and the histories of colonial and imperial adventure leave their traces, including the Balkans. Moreover, various contemporary processes stimulate the appearance of new figures and stereotypes for ‘others’ on local, national, regional, international and global levels.

Education is one of the most powerful agents for constructing and/or deconstructing “otherness” in diversified societies, and has played a significant role in social, historical, and cultural developments in terms of shaping present understandings of past experiences and received imaginaries. It therefore has to be a central pillar in efforts to overcome prejudice, hate speech, and hate crimes in our time. Such education, both formal and informal, should take diverse forms, be energetically promoted, and make use of all available technologies, traditional media, and new media.

Screening at the International Documentary and Short Film Festival - Dokufest. Prizren, Kosovo.

*******

This essay is based on a paper published in the conference proceedings of the 5th International Conference Ohrid- Vodici 2017: “Runaway World, Liquid Modernity, and Reshaping of Cultural Identities, Heritage, Economy, Tourism and Media.”

1. “The longest century of the Empire” is a work by the Turkish historian Ilber Ortayli devoted to “Tanzimat,” a term designating the period of reforms implemented in the Ottoman Empire in all spheres of social-political life that began with proclamation of the Gülhane Hatt-i Sharif (Edict of Gülhane) in 1839. With this proclamation, all people of the Empire were legally equalized, although the Tanzimat reforms were implemented for several decades after they were proclaimed (1839–1876).

Anderson, B. (1991). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso, London

Barth, F. (1969). Introduction. In Barth, F. (ed.) Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: The Social Organization of Cultural Difference. London, pp. 9-38. Etničke grupe i nihove granice. In Putinja, P., Stef-Fenar, Ž. Teorije o etnicitetu, Beograd, 1997.

Bauman, Z. (2000). Liquid Modernity. Polity Press, Malden USA

Giddens, A. (2002). Runaway World: How Globalization is Reshaping Our Lives. Routledge, New York

Krejci J. & Velimisky V. 1996, “Ethnic and Political Nations in Europe.” In Hutchinson J. & Smith A.D. (ed.) 1996. Ethnicity. Oxford University Press, Oxford-New York

Kymlicka, W. (1999). Ethnic relations and Western Political Theory. In: Habitus, Novi Sad

Mazower, M. (2000). The Balkans: A Short History. Widenfeld & Nicolson Book, UK

Mowrer, P. Scott (1921). Balkanized Europe: A study in Political Analysis and Reconstruction. New York: E.P. Dutton

Mursic, R. & Jezernik, B. (2007). “The Balkans in/and Europe.” In Jezerni k B., Mursic R and Bartulovic A. (ed.) Europe and its Other, Department of Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology, Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana

Said, E. (1979). Orientalism. Vintage Books, New York

Taylor, Ch. (1995). Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition. Princeton University Press. Translated into Macedonian by Чемерски О., 2004, Мултикултурализам: Огледи за политика на празнавање, Евро-Балкан Пресс, Скопје

Todorova, M. (1997). Imagining the Balkans. Oxford University Press, Inc. New York, USA, trans. I. Isakoski and P. Volnaroski, 2001, Magor, Skopje

Žagar, M. (2010). “Some Newer Trends in the Protection and (Special) Rights of Ethnic Minorities: European Context.” In Minorities for Minorities, Center for Peace Studies, Zagreb