Male Honor as a Cause of War

archive

Undated photo released by North Korea's Central News Agency (KCNA) on March 7, 2017 shows the launch of four ballistic missiles by the Korean People's Army (KPA) during a military drill at an undisclosed location in North Korea. (Source: AFP/Getty)

Male Honor as a Cause of War

There is now a literature proposing male honor as the main cause of most wars.1 This idea is closely related to studies of wars caused by male leaders seeking revenge for humiliation from earlier defeats (Lindner 2006; Lacey 2009). Examining the role of male honor might help to understand the causation of many wars, past and present. For example, the origins of WWI could be better understood in this way. It is still a puzzle to most researchers, as can be seen in the highly regarded study by Clark (2012). After reviewing the data and the other studies of how the Great War began, he seems at the end to be saying that the nations that fought it were more or less equally involved in starting it.

However, recently it is becoming clear that France played the greatest part in starting the war and that revenge for an earlier defeat by a group of smaller German-speaking countries in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 was a decisive factor. Prussia and its allies, while smaller than France in geographical size and population, appear to have been victorious due to their superior mobilization and weapons. For 41 years (1870-1914) French politics and media were dominated by the cry for revenge.2 One of the principle voices in the French media of that time, a high-ranking general in the French army named George Boulanger, was known as “General Revanche.”

More recently, three US wars—Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan—can be understood largely as attempts by then presidents to uphold their own honor. Given the danger of war now, especially with countries like North Korea that can use nuclear missiles, are there any steps that can be taken to make war less likely? One would be to install leaders in male-female pairs: the office of the US President would be filled by two persons, not just one. Like men, most women have honor issues, but they are usually closer to home and therefore less controlling by comparison with most men in dealing with inter-nation matters. The current president, Donald Trump, exemplifies the dangers of a male as sole leader. Since he communicates impulsively and doesn’t seem to plan all of his comments, even those to leaders of other nations, he could easily start a war involuntarily. Even having two males as co-leaders would probably be less dangerous than just one, since they would likely have to consult with each other before releasing their highly visible statements.

If male honor is so intensely offended by humiliation as to cause wars, why haven’t more studies taken this direction? One possibility is that shame and its slightly less offensive name humiliation are offensive to most members of modern societies. The psychologist Gershon Kaufman (1980; 1989) suggested that they are taboo, in a way similar to the way that sex is still not mentioned openly in proper conversation. The word shame, the “s-word,” seems to be just as offensive as the “f-word.” Humiliation and embarrassment, on the other hand, are also references to shame, but are somewhat less offensive.

The taboo is also implied in the many studies of shame that do not use the forbidden word at all. Instead, the focus is on one of the many shame cognates.3 These substitutes serve to hide the underlying unity of the various terms. One way of hiding shame is to behaviorize it: there are many studies of feelings of rejection, loss of social status, or the search for recognition. For example, Rosen’s 2005 book on the causes of war mentions anger and fear, but not pride or shame. As a substitute, “status attainment” is suggested as a cause. Surely “status” involves shame and pride primarily.

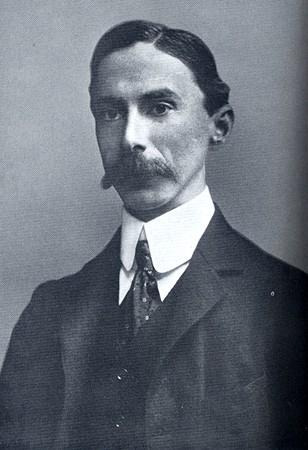

Bertrand Russell in 1907

Shame/humilitation is clearly the central thesis in some texts where it does not appear in the title, such as Lindmann’s 2010 study of the causes of war. Moisi’s (2009) volume has humiliation in the subtitle, but it is only one aspect of the three causes in the central thesis, and the word shame is never used. There are many other studies of what I would call the role of hidden shame in causing war, but masked under one of the many substitute words that Retzinger (1991) has named. One example is Carson’s work on “saving face” in relation to the US role in the Korean War (2016). Although neither Carson nor any of the other articles on war and face-saving state that it is specifically males that are saving face by engaging in war, as argued above, it is certainly implied. If it can be proven that many wars are principally caused by hiding shame, such work might help to avoid further wars.

The term vanity war seems to have been coined by Bertrand Russell (1915) when he explained why he refused to fight in the 1914-18 war. Russell was one of the few people who noticed and acted upon this idea. He refused to fight because, as he actually stated, it was a “vanity war.” He did not go into detail about the nature of vanity, but he did propose the idea of hidden humiliation and shame:

Men desire the sense of triumph, and fear the sense of humiliation which they would have in yielding to the demands of another nation. Rather than forego the triumph, rather than endure the humiliation, they are willing to inflict upon the world all those disasters which it is now (in 1915) suffering and all that exhaustion and impoverishment which it must long continue to suffer. The willingness to inflict and endure such evils is almost universally praised; it is called high-spirited, worthy of a great nation, showing fidelity to ancestral traditions. The slightest sign of reasonableness is attributed to fear, and received with shame on the one side and with derision on the other.4

Russell received no reward for actively opposing the war. Indeed, he spent eight months in prison for it.

The Iraq and Afghanistan wars might also be understood as mass killing occasioned, at least in part, by humiliation. The motivation of the leaders who launched these wars is more complex than that, but even for them war can be seen as partly motivated by revenge, and the use of revenge to placate the public. Rather than acknowledge the shame caused by 9/11 happening on their watch and duly apologizing, they masked it with an attack on a nation that played no part. Like other spree killers, most of their victims were innocent bystanders.

"Men desire the sense of triumph, and fear the sense of humiliation which they would have in yielding to the demands of another nation."

Perhaps the crucial question is not about the leaders, but the public. Why have they been so passive about wars that are obviously fraudulent, and for which they must pay with their taxes, some even with their lives? It is possible that the only thing they have to gain is continuing to mask their fear, grief, and humiliation with anger and violent aggression committed in their name. Needless to say, this is only a hypothesis, like all the others proposed here. Given the current world situation, further exploration and study is urgently needed.

The need for public understanding of the part that the social-emotional world might play in generating violence can be illustrated by studies of the motivation of terrorists. A remark by former prime minister of Israel, Ariel Sharon, frames our dilemma. When asked by a reporter why Palestinians crossing the border are kept waiting so long, he replied: “We want to humiliate them” (2010). According to the theory, the humiliation–revenge–counter revenge cycle is the most dangerous thing in human existence, even more than plutonium. We are jeopardized because emotional motives are virtually invisible to politicians and the public as well. Our job as social scientists and as citizens is to try to make the social-emotional world visible, and as important to national policy-making as the political-economic one.

1. See for e.g. Frevert 2014.

2. See Hall and Ross 2015; Hall 2017; Offer 1995; Scheff 1994; Scheff et al., 2018.

3. See Retzinger 1991, who lists hundreds. See also Scheff, T. and S. Mateo, 2016.

4. See Russell 1915, p. 142.

Carson, Austin. 2016. “Facing Off and Saving Face: Covert Intervention and Escalation Management in the Korean War.” International Organization, Volume 70, Issue 1.

Clark, Christopher. 2012. The Sleepwalkers. New York: HarperCollins.

Frevert, Ute. 2014. “Wartime Emotions: Honour, Shame, and the Ecstasy of Sacrifice. International Encyclopedia of the First World War. 1914-1918.

Hall, Todd. 2017. On Provocation: Outrage, International Relations, and the Franco-Prussian War. Security Studies, Nov., pp. 1-29.

Hall, Todd and Andrew Ross. 2015. “Affective Politics after 9/11.” International Organization May, pp. 1-14.

Kaufman, Gershen. 1980. Shame. Cambridge, Mass.: Schenkman.

- - - - -. 1989. The Psychology of Shame: Theory and Treatment of Shame-based Syndromes (2nd ed.). New York: Springer.

Lacey, David. 2009. The Role of Humiliation in Collective Political Violence. Sydney: University of Sydney.

Lindemann, Thomas. 2010. Causes of War: The Struggle for Recognition. Colchester, UK: ECPR Press.

Lindner, Evelin. 2006. Making Enemies: Humiliation and International Conflict. Westport CT: Praeger Security International.

Moisi, Dominique. 2009. Geopolitics of Emotion. New York: Anchor.

Offer, Avner. 1995. “Going to War in 1914: A Matter of Honor?” Politics & Society v. 23, pp. 213 – 224.

Retzinger, Suzanne. 1991. Violent Emotions. Newbury Park: Sage.

Rosen, Stephen. 2005. War and Human Nature. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

Russell, Bertrand. 1915. “The Ethics of War.” International Journal of Ethics, 25, 2 (January 127–142).

Scheff, Thomas. 1994. Bloody revenge: Emotion, Nationalism and War. Westview Press: Boulder.

Scheff, T. and S. Mateo. 2016. “The S-Word is Taboo: Shame is Invisible in Modern Societies.” Journal of General Practice 4:217.

Scheff, G. Reginald Daniel, and Joseph Loe-Sterphone. 2018. “A Theory of War and Violence.” Aggression and Violent Behavior 39, pp. 109-115.