Re-Globalization in Latin America: Can Turmoil Lead to Reforms?

archive

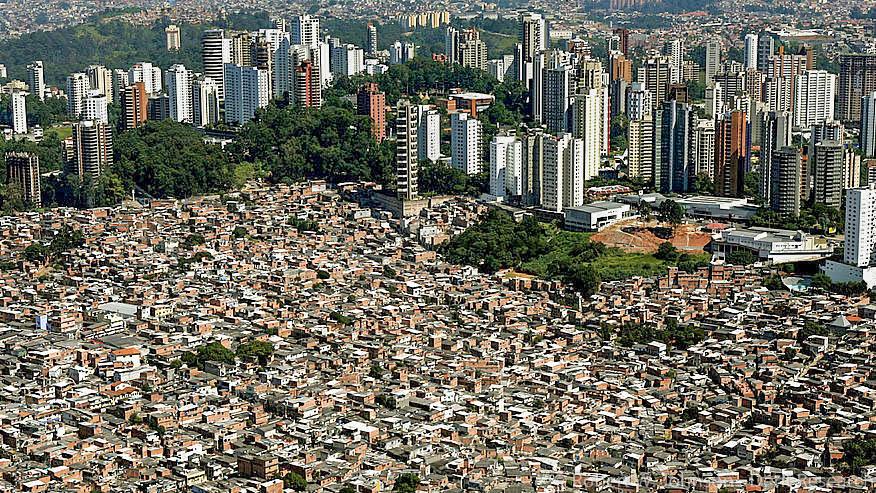

Source: AFP via Getty Images

Re-Globalization in Latin America: Can Turmoil Lead to Reforms?

All of Latin America burns. Literally. Nicolás Maduro’s dictatorship in Venezuela, the populisms of Andrés López Obrador in Mexico and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, the dismantlement of Peru’s congress by its president and the social crises in Ecuador, Chile, Colombia, and Bolivia: the whole continent is in upheaval. Profound changes are in sight and perhaps even imminent, one example being the debate over a new constitution for Chile, where even the richest part of the population and the elite admits that the road traveled so far has come to an end. The good news is the classic teaching: Crisis creates consciousness. Could Latin America’s turmoil ultimately lead to profound and substantial systemic reforms that could become a blueprint for reforming globalization as a whole?

In the important framing essay for this series, Roland Benedikter and Ingrid Kofler have described current global change very accurately and have rightly pleaded for a five-fold model of “Re-Globalization.” In my view and in that of most Latin American’s, all five “R’s” are necessary, if not unavoidable, and must be seen as an interconnected whole. Yet I believe that from a Latin American (and perhaps Global South) point of view, the main two challenges for re-globalization over the coming few years will be “reframing” and “reforming.”

How did Latin America End Up Like This?

The roots of Latin America’s (LATAM’s) discontent are its extractive institutions, “designed to extract incomes and wealth from one subset of the society to benefit a different subset.”1 The Spanish and Portuguese empires established commodity-based economies where locals worked and settlers enriched. Inequality was not reduced during the 19th and 20th centuries, and this eventually led to social crises and civil wars. Then dictatorships arrived. Since the 1970s, military coups have occurred all over the continent. After too much time spent fighting, those impoverished governments received loans at very low rates, but by then fiscal responsibility was not an important priority.

In 1989 the U.S. had just won the Cold War. Yet it perceived that the menace of socialism was still alive south of the border, so the U.S. summoned the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund to renegotiate loans and advise the governments of LATAM countries to handle the debt crisis through austerity measures. They suggested reducing deficit budget and inflation rates, reforming trading conditions to facilitate more participation in the global economy, and reducing state intervention, promoting privatization instead.

Seemingly overnight, LATAM governments had democracy and a role in the world economy. The U.S. assumed that this would foster more inclusive institutions. Instead, the extractive institutions simply adapted their practices and resorted to their old ways.

The 21st Century: Extractive Institutions Pass the Buck

After three decades of explosive economic growth, during which the region more than doubled its GDP between 2000 and 20172 and reduced poverty rates by 14 percent,3 poverty began to rise again in 2016 as growth stagnated. This can be attributed to two main factors:

The Dutch Disease. Coined by The Economist, this term refers to a boom of commodity exploitation, orienting capital and whole economies to that activity. This causes productivity to decline because other sectors of a national economy stop receiving investment and they furthermore become less competitive in international markets because the local currency gets stronger. It is a LATAM-wide “disease” now: resource-rich countries are running out of capital to add value to their commodities.

Excess inequality. Income inequality also declined during the boom, but recently the trend is diminishing. The S80/S20 index decreased from 20.9 in 2002 to 13.1 in 2017.4 The European Union’s average is five. Also, the rate of reduction is declining: from 2002 to 2008 the Gini index’s rate reduction was 1.3%; from 2014 to 2017 it plunged to 0.3%.5 Finally, according to ECLAC,6 the concentration of “physical and financial assets is far higher than the concentration of real incomes in LATAM.” This excess of inequality impacts people’s well-being7 and social mobility—and therefore also affects productivity—as well as support for democracy and the development of state capacities.

When one combines the Dutch disease with an excess of inequality, the result is institutional mistrust. Fifty-three percent of Latin Americans declare that corruption has increased in their countries.8 This is typical of extractive societies, where corruption finds an easy foothold, and LATAM is full of them: Mexico, Panama, Brazil, Peru, and Argentina are the most well-known cases.

Reforming Globalization for LATAM

All international recommendations point in the same direction: redistribute economic and political power, and transition to more inclusive institutions. It is suggested that these societies need to focus on promoting the participation of traditionally excluded groups in commerce and the job market; investing in early education; reforming their tax laws; promoting a Public Integrity Agenda, and investing in fiscal and legal state capacities.

One of the proposals for overcoming the crisis has been the agreement in Chile to pursue a new constitution. The country has had four until now, the first being promulgated in 1828 and the next two in 1833 and 1925 respectively. The last and most controversial was promulgated by Augusto Pinochet in 19809 during his military dictatorship, and it is this constitution that prevails to this day. It established the notion of the “subsidiary state,”10 limiting government intervention exclusively to guaranteeing public order and the functioning of markets, and exempting the state of any obligation as provider of basic social services. Since the return to democracy in 1990, Pinochet’s constitution was reformed once in 2005, but it has not been replaced.

A New Constitution for Chile: Exemplary Reform?

In November 2019, the Chilean government and its opposition agreed to start a new constitutional process.11 In the beginning they focused on more and better public services as a tonic for social unrest. Having failed on that diagnosis, however, élites concluded that it was more of an institutional problem: the prevailing constitution from the time of Pinochet’s dictatorship lacked legitimacy. Changing it could reshape Chilean extractive institutions into more inclusive ones. “The most relevant point of this new process is that it will start as a tabula rasa, dismissing 1980’s Constitution and doing a completely new one,” says Pablo Contreras12 from Autonomous University of Chile.

All international recommendations point in the same direction: redistribute economic and political power, and transition to more inclusive institutions.

In the second place, this will be the first time that Chileans could vote on both the mechanism and the ratification of the law. According to Marcela Ríos,13 from UNDP Chile, “The process is as important as the content of this new Constitution; it has to be participative, transparent, diverse. I hope we have community leaders, women, and representatives of the native people.”

What should this new constitution portend? “It has to be flexible enough to leave freedom for each government’s agenda, but it also has to be very clearly delineated in three areas: power organization and distribution, the role of the forces of public order, and the fundamental rights of the people. We have to discuss if we want a ‘subsidiary state’ or a social and democratic one,” says María Jaraquemada,14 from the think tank Espacio Público. Moreover, Ríos argues that social welfare and income distribution will be very important.

The process itself has not started as sure-footedly as expected. Many are skeptical that congress members will put fundamental reforms ahead of campaign politics. Indeed, the question remains whether a new Chilean constitution can be exemplary. Jaraquemada says: “We know that the region has its eyes set on us. The other countries think that if this process fails here, it won’t work in any other Latin American country.”

Reframing Globalization for LATAM

According to the OECD,15 strengthening international bonds could help LATAM to adopt nationally-driven development processes and create new capacities to adapt to national and global reforms. Many look to Europe as a potential partner, but the last joint effort was a 2019 Free-Trade Agreement with one of the most important blocs of LATAM, the Mercosur. Putting the agreement into effect has been politically complicated for both parties. Meanwhile, the Pacific Alliance, another regional bloc composed of Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru, is eager to strengthen its collaboration with Asia and the Pacific.

What does all this this mean with regard to Benedikter and Kofler’s proposed 5Rs of Re-Globalization? For LATAM it is urgent not just to reform but also to reframe the way that its states are contributing to social order and welfare. Strengthening regional collaboration, especially with the EU, could be a huge opportunity for both sides. LATAM’s leaders and citizens could learn better ways to articulate a vision for their societies, pursuing paths to effective and lasting development. As for the EU, it could benefit from new modes of creativity and expanded relationships with Latin America and the Pacific Rim, offering returns on both financial and social capital. If mutually beneficial relationships evolve out of these initiatives, they could provide a valuable model of how to develop the Global South—and thus get globalization back on track in a better way.

1. Acemoglu, D. & Robinson, J. (2012) Why Nations Fail: the origins of power, prosperity and poverty. Crown Publishers, New York.

2. https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDP_RPCH@WEO/WE

3. https://cepalstat-prod.cepal.org/cepalstat/tabulador/ConsultaIntegrada.asp?idIndicador=3328&idioma=e

4. https://cepalstat-prod.cepal.org/cepalstat/tabulador/ConsultaIntegrada.asp?idIndicador=3295&idioma=e

5. ECLAC (2019) Fiscal Panorama of Latin America and the Caribbean 2019, Santiago, Chile.

6. ECLAC (2019) Social Panorama of Latin America and the Caribbean 2019, Santiago, Chile.

7. OECD (2019) A Broken Social Elevator? How to promote Social Mobility. Paris, France.

8. Latinobarómetro Survey 2019.

9. https://www.bcn.cl/historiapolitica/constituciones/detalle_constitucion?handle=10221.1/17659

10. Renato Cristi, El Pensamiento Político de Jaime Guzmán. Autoridad y Libertad, Ediciones Lom, 2000, Santiago, 223 p.

11. You can downoload the Agreement here: https://www.senado.cl/logran-historico-acuerdo-para-nueva-constitucion-participacion/senado/2019-11-14/134609.html

12. PhD Law, Northwestern University. Professor of Law in the Autonomous University of Chile.

13. PhD Political Science, Wisconsin University. Coordinator of Governance Area UNDP Chile.

14. LLM, University Carlos III of Madrid. Influence Director in Espacio Público.

15. OECD (2019). Latin America Economic Outlook 2019. Paris, France.