Which History are we Trapping Ourselves in? On Nubians in Egypt, Collective Memory and Sexuality.

archive

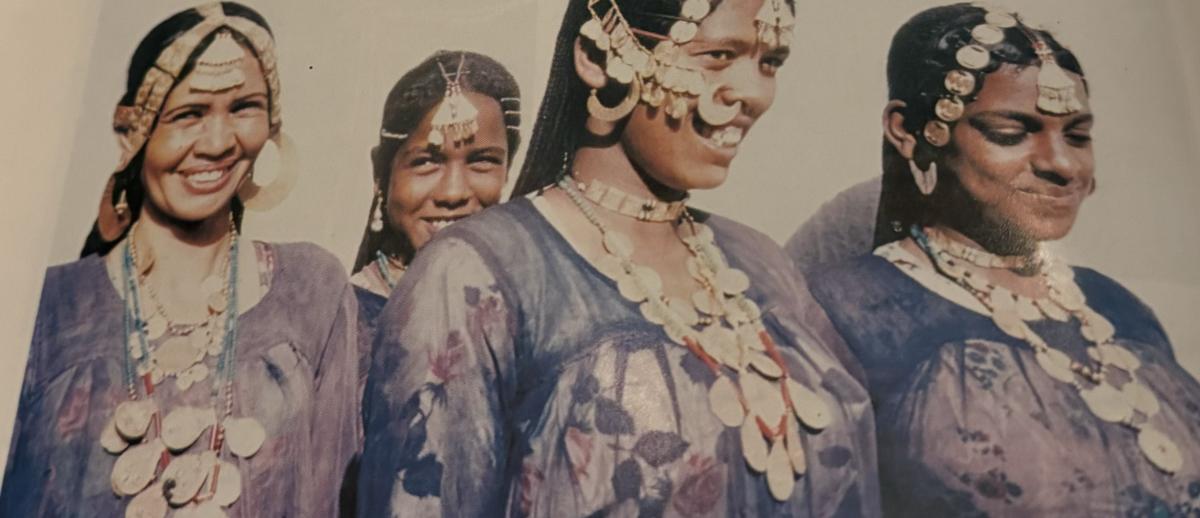

Women from Korosko: Riad, M. and Abd El -Rasoul, K. (2010). Rehla fi Zaman Al Nuba [Journey in the Time of Nubia]. 2nd ed. Cairo: General Egyptian Book Organisation.

Which History are we Trapping Ourselves in? On Nubians in Egypt, Collective Memory and Sexuality.

This article explores the identity and collective memory of the Nubians, a group currently spanning Egypt and Sudan, transformed by development-induced displacements like the Aswan High Dam project. It examines the impact of displacement on Nubian culture and identity, particularly focusing on the collective memory that shapes their modern sense of self. Yet, this collective memory is discerning, sidelining certain narratives and, notably, diminishing the visibility of queer identities, exemplified by the overlooked story of Ibrahim Al Gharbi, a queer Nubian sex worker. Rather than preserving the entirety of Nubian heritage, this collective memory permits mainstream culture to define acceptability, employing collective censorship to sculpt a “suitable” image of the past. The author will provide insight into their own experience with this.

The memory of a far-gone past, or collective memory to be precise, is integral to minorities' identities today. However, these memories are merely a perspective through which individuals interpret their past and present to create an understanding of them that forms their futures (Stock 2010). Moreover, collective memories spanning generations can be shaped by interests, desires, political climates, and fantasies. This is a continuous process of interpretation and reconstruction, allowing for individuals and groups to pass, (re)construct, and perform their identities even when international borders divide them as it does with Nubians in Egypt and Sudan (Agnew 2005; Hua, 2005).

The story of Ibrahim Al Gharbi, a Nubian individual born in the 19th century in the Old Nubian village of Korosko, might not tell us everything about how Nubian collective memory works, but it does inform us about what Nubian collective memory failed to preserve. While refusing to uphold the historical racial hierarchy and promote Nubian identity, it, being Nubian collective memory, upheld a sexual hierarchy by censoring stories about sexual minorities. Through partial assimilation into the continuously changing dominant culture and to avoid complete marginalization, Nubian collective memory failed to acknowledge the diversity of its own narratives while asking the majority to embrace diversity. By doing so, it continues to uphold a racial hierarchy in memory.

Who are the Nubians?

Nubians, historically recognized as an ancient civilization, today represent a vibrant transnational community spanning modern Egypt and Sudan, united by shared culture and language despite diverse socio-political contexts. Nubia today is not at all what it used to be up until just 121 years ago. The land that once extended from the first cataract south of the city of Aswan in Egypt to the fifth cataract in the north of Sudan has undergone significant changes over the last two centuries, marked by displacements and labor migrations due to marginalization and DIDR (Development Induced Displacement and resettlement) projects (Saleh, 2023). Within Egyptian Nubia, the Nubian population consists of three linguistically and culturally distinct groups, The Kenuz (Mattoukki), The Arabs, and The Fadicha, residing in the area from Aswan all the way south to the borders with Sudan, respectively (Saleh 2023).

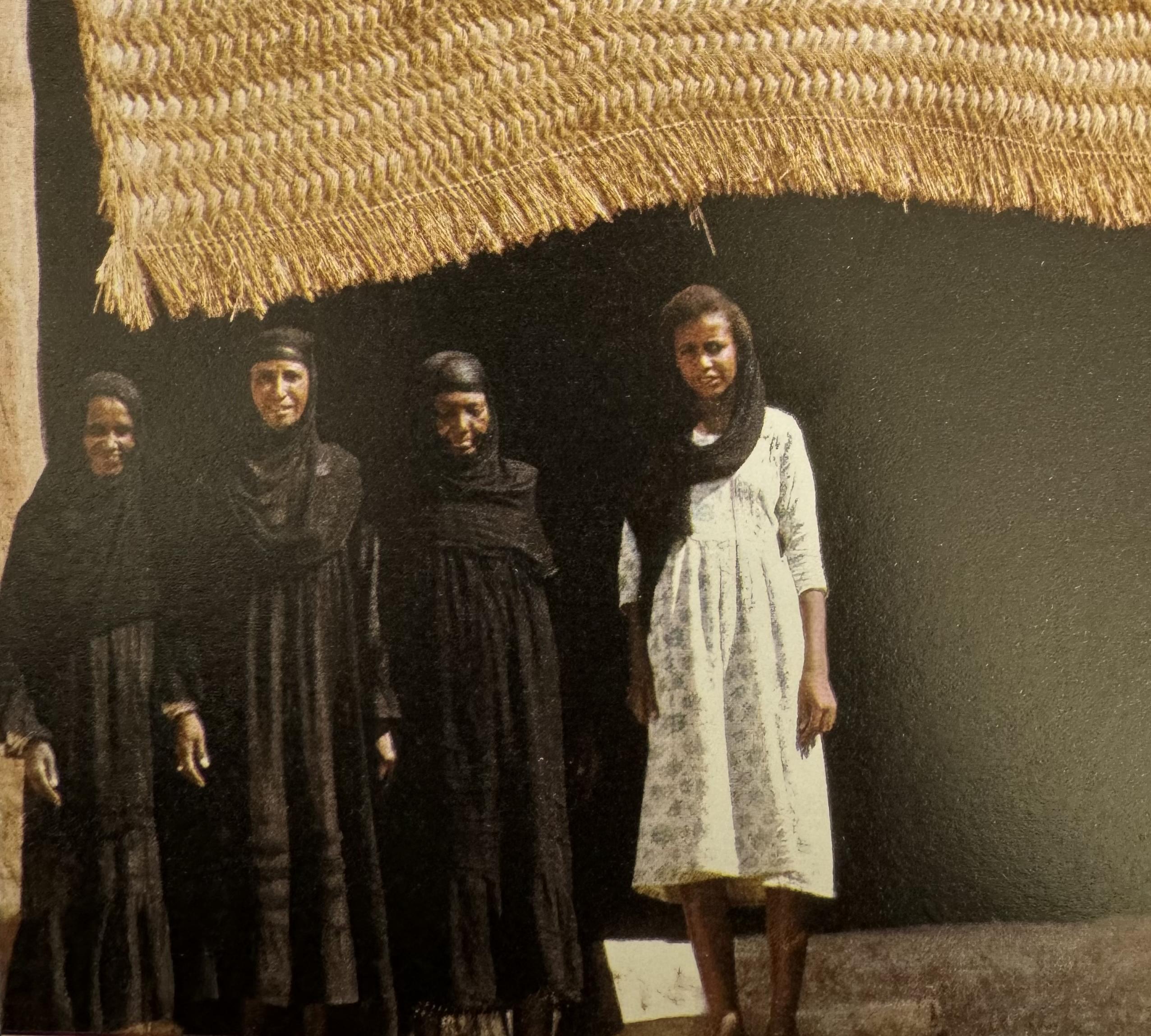

Women from ther southern villages in Egyptian Nubia | Mousa, Adel. and Saleh, Mohie El-din (2012). Ayam Nubiya: 'An Rihlet Professor Anna Hohenfarth [Nubian Days: On professor Anna Hohenfarth Journey]. Cairo: General Egyptian Book Organisation.

The most significant displacement occurred in 1964 with the construction of the Aswan High Dam, which submerged the entirety of Nubian territories within Egyptian borders and parts of Sudan. Those in Egypt were uprooted and sent to state-built settlements to the north of Aswan (Saleh 2023). The displacement took place in a context of decolonization and the rise of the nationalist Nasser's regime. The dam project itself, which became a cooperative effort with the soviet union, was portrayed as an act of resistance to the Western colonial powers that were doing everything possible to stop the progress of a liberated and decolonized Egypt.

The Place of Collective Memory

Submerging the entirety of Egyptian Nubia inaugurated an era of erasure. It registered a moment of loss that changed the sense of Nubian identity and how Nubians look at their ancient and modern history. Nubians kept the memory of their old homeland alive, an image that younger generations inherited, coupled with a sense of a displaced identity (Agha 2019). This image of the past, together with their current identity of displacement, ignited an active struggle through the generations, demanding recognition of cultural rights and a return to the ancestral homeland on the banks of the Nile (Janmyr 2016). The effort to reconstruct and rejuvenate a society based on memory placed the Nubian past in the space of nostalgia, where the past is not just romanticized, but operates as both deeply personal and collectively shared in the community. The collective characteristic, in particular, was shaped by a shared experience of being raised on the stories of Old Nubia, what it looked like, how village life operated, and how society was structured. (Saleh 2023). These stories of Old Nubia and these idealized images of the past became the reference for what it means to be Nubian. Being Nubian is always seen in relation to Nubia as seen and mourned in Nubian collective memory (Saleh 2023). Displacement also drastically altered Nubian conceptions of identity. Historically, Nubians lived in a large region that predated the nation-state, and contact with those outside of their communities or sub-groups was uncommon, and a singular Nubian identity was nonexistent. The displacement created a sense of collective "Nubianness" among post-displacement generations, particularly in those Nubian communities in larger Egyptian cities such as Cairo, Alexandria and Ismailia. Those not in the urban centers were sent to "displacement settlements." (Saleh 2023). Based on shared memories, this collective identity grounds an imagined kinship, an imagined community that is believed to be real, As real as Nubians' skin colour and ancestry (Anderson 2016).

What We Don't (want to) See in Our Collective Memory

What makes this memory, despite being altered, a very precious part of Nubian identity? Firstly, collective memory is what remains for Nubians and is difficult to question. Even those who do question it privately face many more challenges in doing so publically, where Nubians, their culture, heritage, and languages are marginalized. Secondly, it is this juxtaposition between Nubians as a minority and Egyptians, the majority, that also transformed memories into tools of survival while pushing many Nubian stories into oblivion. Unfortunately, it is far too easy to send stories of sexualities into this oblivion; sexualities that do not fit in the norms of either societies, Egyptian or Nubian.

One of these stories is that of Ibrahim Al Gharbi, a Nubian individual born sometime in the 1850s in the Old Nubian village of Korosko. As the author, I will be personally speaking from this point on and providing personal reflection. Ibrahim is most known for two things, at least in everything I could find about them: for being the wealthiest and most powerful brothel owner in Cairo and for a very fluid gender identity. Ibrahim would be seen publicly dressed as a woman, wearing makeup, and with a body covered in jewellery and gold, "a moral deviance" that showed on them after a trip to Sudan. Before that, Ibrahim was told to be a religious, respectful son to a respected and rich village leader (Cormack 2021). Sadly, Ibrahim has not left any memoirs about their life that can tell us how a Nubian child from Korosko managed to become the "Emperor '' of 1920s Cairo nightlife before dying in prison in 1926 (Cormack 2021).

Photo of Ibrahim Al Gharbi | https://cairo52.com/ibrahim-el-gharaby-the-pimp-emperor/

Everything that is available to read about Ibrahim1 is either from official records that are obviously keen on moralizing Ibrahim's existence or the memoirs of individuals who detested everything about Ibrahim. White journalists and Harvey Pasha, the chief of Cairo's Police in 1916, for example, were very clear about their abhorrence of Ibrahim's race, sexuality, gender expression, and type of work they had. Records show that not only was Ibrahim explicitly and shamelessly public about the fluidity of their gender and sexuality, but he was also involved in human trafficking. Ibrahim's enormous wealth and power, at least over Cairo's nightlife community, came from selling minor girls in the several brothels they owned (Cormack 2021). This is what the official record shows; however, Ibrahim's story, from their perspective, is nowhere to be found.

As a Nubian individual first and a researcher second, I lack first hand sources to understand the experiences of a Nubian queer sex-worker in early 1900s Egypt. Without personal narratives, I cannot grasp how race and sexuality influenced the life of someone like Ibrahim, their identity, or their decisions. I am left with only documents that either moralize their existence, embedding them in a polarized collective memory, or erase them through censorship.

Conclusion

Instead of safeguarding all aspects of Nubian culture, the collective memory has allowed the dominant culture to dictate what is acceptable, using collective censorship to craft an accepted image of the past. However, censoring the past does not make it look better; instead, it creates a distorted version that complicates our present. Our past and our memory will remain troubling as long as we refuse to deal with it and create a better understanding of it (Baldwin 2012). Engaging with memory has been a crucial part of the survival of minority groups everywhere in the world, such as queer Nubians. Memory offers a sense of belonging when alienated, marginalized, and surrounded by confusing representation. Memory can create space across borders and time that connects the pieces of ourselves and identities in order to give us a reference to relate to, (re)construct our identities, (re)build our communities, and (re)create spaces where we can resist and diminish the hostility of alienation.

1.It was easy to find many more versions of the same republished story in Arabic and on many sensation-seeking websites and blogs, but mostly with no references.

'Agha, Menna. 2019. ‘Nubia Still Exists: On the Utility of the Nostalgic Space’. Humanities 8 (1): 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8010024.

Agnew, Vijay. 2005. ‘Introduction’. In Diaspora, Memory, and Identity, edited by Vijay Agnew. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Anderson, Benedict R. O’G. 2016. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Revised edition. London New York: Verso.

Baldwin, James. 2012. Notes of a Native Son. Revised ed. Boston: Beacon Press.

Cormack, Raphael. 2021. Midnight in Cairo: The Female Stars of Egypt’s Roaring ’20s. First edition. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

Fanon, Frantz. 1997. Svart hud, vita masker [Black Skin, White Masks]. Translated by Stefan Jordebrandt. Gothenburg: Daidalos.

Hua, Anh. 2005. ‘Diaspora and Cultural Memory’. In Diaspora, Memory, and Identity, edited by Vijay Agnew. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Janmyr, Maja. 2016. ‘Nubians in Contemporary Egypt: Mobilizing Return to Ancestral Lands’. Middle East Critique 25 (2): 127–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/19436149.2016.1148859.

Saleh, Yahia. 2023. ‘To Identify with a Memory: A Case Study on Nubian Post-Displacement Ethnic Identity in Contemporary Egypt’. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1794951/FULLTEXT02.

Stock, Femke. 2010. ‘Home and Memory’. In Diasporas: Concepts, Intersections, Identities, edited by Knott Kim and McLouglin Sean. London: Zed Books.