Islam, Social Justice, and the Global Refugee Crisis

archive

Islam, Social Justice, and the Global Refugee Crisis

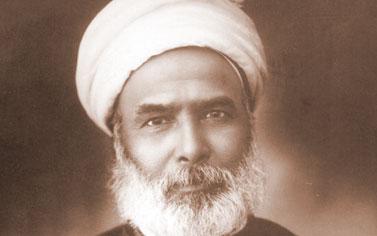

The nineteenth century Egyptian scholar and jurist, Muhammad ‘Abduh, once said: “I went to the West and saw Islam, but no Muslims; I got back to the East and saw Muslims, but not Islam.” Two hundred years later, this statement remains a prescient observation about the strength of non-Muslim majority countries in the West and of the shortcomings of many Muslim-majority governments in the Middle East and North Africa—particularly in light of the global refugee crisis. Millions of who suffer intolerable misery and human rights violations, often at the hands of their own leaders, are fleeing war and persecution in Muslim-majority countries like Syria, Iraq, South Sudan, and in Muslim-dominant areas in Myanmar. Yet, the citizens and oftentimes the lawmakers of Western (non-Muslim majority) countries are standing up for the rights of these refugees whilst the governments of many Muslim-majority nations are staying silent.

Despite many American lawmakers’ support for refugees, American president Donald J. Trump signed an executive order to suspend entry of all refugees for 120 days and barred those fleeing the civil war in Syria indefinitely. In addition, the executive order imposed a 90-day ban on entry to the US on citizens from seven countries: Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Syria, Sudan and Yemen. President Trump signed this executive order, often referred to as the “Muslim ban,” by invoking the September 11, 2001 attacks. The move came as no surprise to those following, and even supporting, his presidential campaign. One of the proposals propping up his campaign platform was to institute a so-called “Muslim ban” and, in fact, the United States has a history of banning certain groups or nationalities despite the Statue of Liberty’s beacon call to immigrants worldwide. Most of the 19 plane hijackers who perpetrated the 9/11 attacks, however, were from Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt and Lebanon—none of these countries are included on the executive order’s ban list.

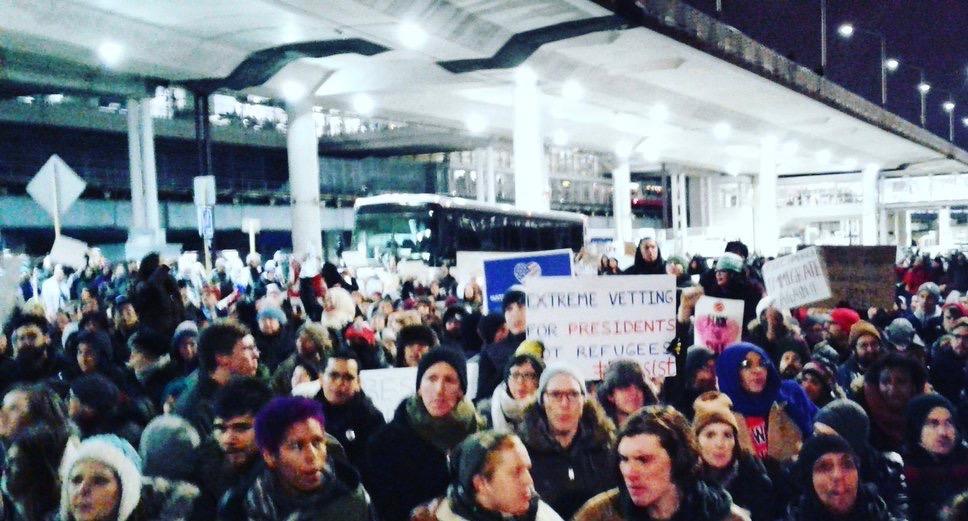

President Trump’s ban sparked an outraged response from millions of citizens and political leaders in non-Muslim majority societies who raised their voices in defiant opposition and took to the streets in protest. Popular protests have taken place in capitals and cities throughout the Western world. In the United Kingdom there were demonstrations across England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, and with them a petition that gathered one million signatures demanding that President Trump’s state visit to the UK later in 2017 be cancelled. Germans, who have so far accepted more than one million citizens from the war-torn country of Syria, also protested. The French, the Canadians, and even some Republican senators in Washington D.C. also stood in open opposition. Moreover, Americans gathered in airports across the country to stand in solidarity with the many people who were being detained because of the executive order.

Besides popular protests against the executive order, there have been legal challenges as well. Indeed, the executive order has since been halted by a ruling of the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, which questioned its constitutionality. Critics have also noted its violation of international human rights laws, in particular the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, which updated the post-World War II Refugee Convention of 1951 prohibiting discrimination on the basis of race, religion, or national origin.

The vociferous objections against the ban and the vocal support offered to refugees stands in stark contrast to the conspicuous silence from leaders of many Muslim-majority nations. The only Muslim-majority nation to condemn the executive order has been Turkey, which has also borne the brunt of the Syrian refugee crisis, yet accepted many into its fold. Deputy Prime Minister and government spokesperson Numan Kurtulmuş told Habertürk, a daily newspaper, that President’s Trump’s executive order was “a discriminative decision. I hope they will correct it.”

The lack of a response from the OIC and the Muslim-majority nation-states it represents is troubling because they are foregoing a legacy of acceptance, social justice, and human rights that underpins Islamic principles.

So why the silence? According to a New York Times report at the end of January 2017, “King Salman of Saudi Arabia, home of Islam’s holiest sites, spoke to Mr. Trump by telephone on Sunday but made no public comment. President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi of Egypt, whose capital, Cairo, is a traditional seat of Islamic scholarship, said nothing. Even the Organization of Islamic Cooperation [OIC], a group of 57 nations that considers itself the collective voice of the Muslim world, kept quiet.”1

The lack of a response from the OIC and the Muslim-majority nation-states it represents is troubling because they are foregoing a legacy of acceptance, social justice, and human rights that underpins Islamic principles. Indeed, the Prophet Muhammad himself was a refugee, fleeing his hometown of Mecca in 622 after years of economic exclusion and social persecution. Finding a haven in Medina, this journey, known as the Hijra, marks the beginning the Islamic calendar (Year 0). The fact that the Islamic calendar is marked in accordance with the Hijra reminds Muslims not to celebrate pomp and glory but to honor sacrifice, as many Muslims at the time had to leave Mecca, the city of their birth, due to persecution. Years earlier in 615, several of Prophet Muhammad’s Companions, men and women, also fled from Mecca to Abyssinia (present-day Ethiopia and Eritrea) to find refuge with the Christian king there.

The silence of Muslim-majority nations is even more disconcerting because through the holy Qur’an, believed by Muslims to be the direct word of God transmitted to the Prophet Muhammad via the Angel Gabriel, Islam explicitly requires the faithful to comply with agreements and treaties on the rights of refugees: “‘O you who believe, fulfil your obligations…” (5:1). It provides a set of instructions for dealing with refugees and migrants, praising those who assist people in distress and requiring the faithful to protect refugees (9:100 and 9:117). The Qur’an also recognizes the rights of refugees and internally displaced persons, entitling them to humane treatment (8:72-75, 16:41). This sacred text also puts forth specific regulations to lend additional support to women and children, who are considered more vulnerable (4:2, 4:9, 4:36, 4:75, 4:98, 4:127, 17:34). And under the principle of justice, which is the basis of all Islamic regulations (42:15, 16:90), those who are more at risk as a result of migration and asylum should be offered extra support. These guidelines are to be observed even in the case of non-Muslims or those who oppose the Muslim faith, as commanded in the following verse: “O you who have believed, be persistently standing firm for God, witnesses in justice, and do not let the hatred of a people prevent you from being just. Be just; that is nearer to righteousness (Qur’an 5:8).” Furthermore, the Qur’an condemns people whose actions prompt mass migration and views them as lacking faith in God’s words (2: 84-86). The teachings of Islam through the Qur’an and the documented life of the Prophet Muhammad teach that social justice, the right to life (6:151), and integrity are rights for all human beings.

In the first few weeks of 2017, Muhammad ‘Abduh’s saying from centuries ago continues to resonate. Indeed, the citizens of Western nations raising their voices against President Trump’s travel ban to support the rights of refugees and immigrants are practicing Islam, a religion that upholds respect, diversity, equality, and justice, and one that has seemingly been abandoned by the governments of many Muslim-majority countries.

published in Tabriz, Persia, 1307. Now in the collection of the Edinburgh

University Library, Scotland.