The Fight for Recognition: The Tularosa Basin Downwinders and the Injustices of Trinity

archive

Trinity test site, July 16, 1945. (Image source: Wikipedia)

The Fight for Recognition: The Tularosa Basin Downwinders and the Injustices of Trinity

In a world searching for sustainable energy infrastructures, the US has still not rectified the injustices that came about with the earliest moments of the nuclear era. On July 16, 1945, when the US government detonated the first atomic bomb at the Trinity Site in South Central New Mexico, officials had little to no concern for the people who lived in the adjacent area. Most of them were people of color, Native Americans and also Hispanos who had emigrated north from Mexico (or their ancestors had likely done so).1 These people were warned neither before nor after the so-called “test” as to the dangers they were facing as a result of the bomb.2 As we know, this “test” would be the first of many from both Western and Eastern superpowers. Within the US context, other communities considered marginal to the US would be devastated; the atomic explosions on the Marshall Islands and their impacts on Indigenous communities are one of the best-known of these horrific accounts. Debates around nuclear power continue to have great international resonance today.3

As documented in written and oral histories recorded by the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium (TBDC), ash fell from the sky for days after the bomb was detonated and settled on everything—the people, the land, and the animals.4 The TBDC was originally organized to bring attention to the negative health effects suffered by the people of New Mexico as a result of their overexposure to radiation as a result of the “test.” Ultimately, the TBDC’S goals include raising awareness and attaining justice for impacted local communities and families.5

Fallout

The bomb detonated at Trinity produced massive fallout that blanketed the earth and became part of the water and food supply that the people of the area rely on for sustenance. The bomb was incredibly inefficient, inasmuch as it was overpacked with plutonium: it incorporated 13 pounds of plutonium when only three pounds were necessary for the fission process.6 The remaining 10 lbs. of plutonium—with a half-life of 24,000 years7—was dispersed in the radioactive cloud that rose over eight miles above the atmosphere, penetrating the stratosphere.8

The bomb was detonated on a platform at a height of 100 feet off the ground, the only time a device was ever detonated so close to the ground. At this height the blast did not produce massive destruction—but it did produce massive fallout. In fact, Trinity produced more fallout than any of the atomic bombs detonated at the Nevada Site.9 In Japan, the bombs were detonated at heights of 1600 (Nagasaki) and 1800 (Hiroshima) feet respectively, which produced massive destruction and the horrific images which we know too well. In contrast, the accounts of communities in southern New Mexico are best characterized by what Rob Nixon calls “slow violence.” Through this concept, Nixon wants us to focus on how environmental degradation that occurs at the hands of human actors can slowly accumulate and impact communities for years after an initial event.10

To understand the exposure received by New Mexicans in the area, it is important to understand the lifestyles of the people living there in the 1940s and 50s. In rural parts of New Mexico in 1945 there was no running water, so people collected rainwater for the purpose of drinking, cooking, and the like. There was no refrigeration, so there were no grocery stores to buy produce, meat, or dairy products. Mercantile stores sold things like sugar, flour, coffee, rice, cereal, and other nonperishables, but all the meat, dairy, and produce that was consumed was grown, raised, hunted locally. Most if not all the food sources were negatively affected by the radioactive fallout that became part of almost everything that was consumed.11

The regional water infrastructures included cisterns, sometimes dug into the ground, to collect water directed off of rooftops. Once inside a cistern, radioactive debris would remain effectively forever (having no place else to go) so that water dipped out of a cistern for drinking or cooking would be replete with radioactive isotopes that were then consumed. Even one particle of plutonium inhaled or ingested would remain in the body giving off radiation and destroying cells, tissue, and organs.12

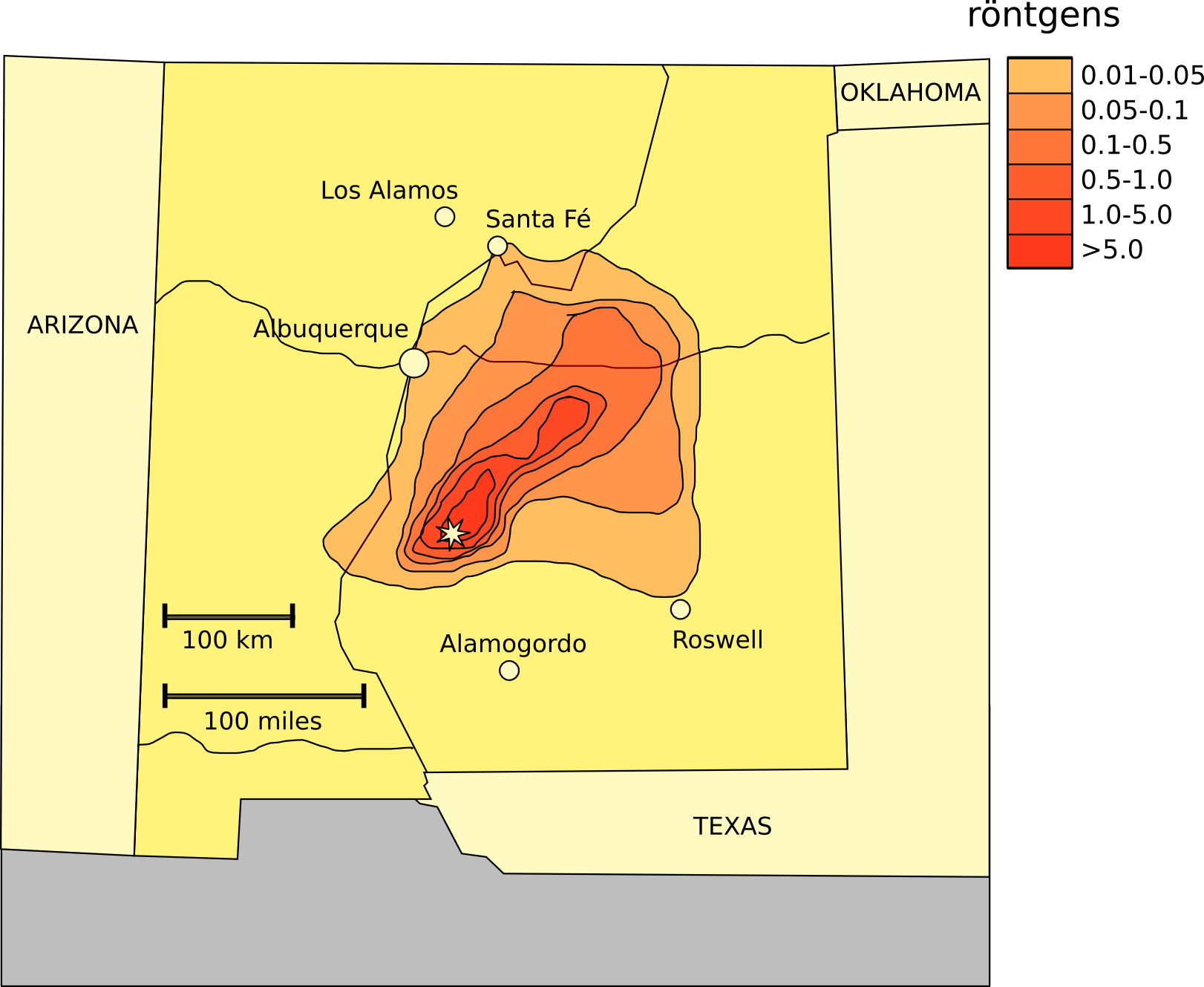

Map of New Mexico showing the contested official area of Trinity test fallout. (Source: Wikipedia)

Denial

People who have shared with the TBDC their stories of the blast that day have said that they thought it was the end of the world. Imagine: the bomb produced more heat and more light than the sun. It was detonated at about 5:30 a.m. and many reported that the explosion “knocked them out of bed.” They said first the sky lit up brighter than day, and then the blast followed. Many said that they were gathered up by their mothers and made to pray. The light is reported to have been seen all the way to California and the blast was felt as far north as Albuquerque. It was an unprecedented event that no one received warning about, and within days a lie was delivered and perpetuated by the US government: a munition dump at the Alamogordo Bombing Range had accidently exploded but no one was hurt, it claimed.13

Another lie told by the government, which continues to be told today, is that the area was remote and uninhabited. Nothing could be further from the truth.14 In reality there were tens of thousands of US citizens—men, women, and children—living in a 50-mile radius of the site. If you expand that radius to 150 miles, it includes Albuquerque to the North and Las Cruces and El Paso to the south, an area that included hundreds of thousands of people. The Mexican city of Ciudad Juárez may also have been impacted, but this seems to have received little consideration.

The bomb detonated at Trinity produced massive fallout that blanketed the earth and became part of the water and food supply that the people of the area rely on for sustenance.

After the bomb was detonated one of the physicians involved admitted that it could never again be done here because people had been so overexposed to radiation, and that in the future the testing program would have to find an area with a 150-mile radius uninhabited.15 Clearly, Trinity was conducted with little to no concern for human nor environmental health. It is reported that some allowances were made to evacuate a few hundred people, but no evacuations were ever made. In this way, the environment of southern New Mexico was invaded by the US government and forever changed. Nothing was the same afterward, and the damage was done. No one really understood the implications—otherwise, local people would not have continued to live off the land.

The US government has never returned to conduct a full epidemiological study on the impacts of this exposure on the people of New Mexico. Yet in 1990, a bill was passed called the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA), which provided recognition, an apology, and reparations to the people living downwind of the Nevada Test Site and elsewhere in the Southwest not counting the region around the Trinity site. So while the people of New Mexico were the first to be exposed to this horrific form radiation anyplace in the world, while they lived much closer to the Trinity test site and were therefore exposed to much more higher doses of radiation, and while they were also documented as being downwind of the Nevada Test site, they have never been included in the RECA fund.16

Documentation

There has been a recent challenge by the National Cancer Institute17 to what we know to be true about the people’s use of cisterns in rural parts of New Mexico. To dispel the idea that people in the 1940’s and 50’s didn’t use cisterns, the TBDC is now undertaking a process for collecting notarized affidavits in which people recount what they remember about how they acquired water for drinking and cooking purposes. Many of the statements are clear about how rainwater was collected mainly in cisterns and that this water was considered a precious commodity. This archival work provides the TBDC with the opportunity to document, for the first time, the memories of local and elderly community members about the region’s water infrastructures and support their efforts for environmental justice. This ongoing archival work was even useful for TBDC’s March, 2021, presentation to the US Congress on the importance of expanding RECA.18

Protesters gather in 2011 along US 380 outside the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico. (Source: Santa Fe New Mexican)

The collection of affidavits is made public so that there is a record of what has been shared with the TBDC through this process. People who wrote the statements in these affidavits are from varying communities across New Mexico, and it is interesting to note that most of them were typically not familiar with each other, yet their statements have many common themes.

The TBDC believes that there is an imperative to document the truth as told by those who experienced the Trinity bomb and know of their living conditions. It is hoped that the affidavits will inform the public as to the inaccuracies that are often told by the government and agencies that represent the government.19 All of this is especially crucial today as nuclear energy has continued to be of great importance globally. Numerous administrations have sought to expand US nuclear power abroad,20 yet as both the US and other governments around the world continue to look towards nuclear, its origins and those present during its origins must no longer be overlooked.

1. Victoria Peña-Parr. “The complicated history of environmental racism.” August 4th, 2020. http://news.unm.edu/news/the-complicated-history-of-environmental-racism

2. Myrriah Gómez. “Unknowing, Unwilling and Uncompensated: The Effects of the Trinity

Test on New Mexicans and the Potential Benefits of a Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) Amendment,” 30. https://www.kob.com/kobtvimages/repository/cs/files/TBDC%20HIA%20final%20report%202-8-2017.pdf

3. Dipka Bhambani. Trump Administration Pivots to Nuclear Energy, Finds Lever Against China, Russia. https://www.forbes.com/sites/dipkabhambhani/2020/08/07/trump-administration-pivots-to-nuclear-energy-finds-lever-against-china-russia/?sh=f3c647547b15

4. Myrriah Gómez. “Unknowing, Unwilling and Uncompensated: The Effects of the Trinity

Test on New Mexicans and the Potential Benefits of a Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) Amendment,” 40. https://www.kob.com/kobtvimages/repository/cs/files/TBDC%20HIA%20final%20report%202-8-2017.pdf

5. See the website of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium for more information: https://www.trinitydownwinders.com/

6. Thomas E. Widner and Susan M. Flack, Characterization of the World’s First Nuclear Explosion, the Trinity Test, as a source of Public Radiation Exposure, 480. Note that we have converted the totals to pounds.

7. Szasz, Ferenc Morton. 1984. The Day the Sun Rose Twice: The Story of the Trinity Site Nuclear Explosion, July 16, 1945. Albuquerque: The University of New Mexico Press.

8. “Trinity Site” at Atomic Heritage Foundation: https://www.atomicheritage.org/location/trinity-site

9. Myrriah Gómez. “Unknowing, Unwilling and Uncompensated: The Effects of the Trinity

Test on New Mexicans and the Potential Benefits of a Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) Amendment,” 42.

10. Nixon, Rob. 2011. Slow Violence and Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

11. Myrriah Gómez. “Unknowing, Unwilling and Uncompensated: The Effects of the Trinity

Test on New Mexicans and the Potential Benefits of a Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) Amendment,” 9. https://www.kob.com/kobtvimages/repository/cs/files/TBDC%20HIA%20final%20report%202-8-2017.pdf

12. Ibid.

13. Szasz, Ferenc Morton. 1984. The Day the Sun Rose Twice: The Story of the Trinity Site Nuclear Explosion, July 16, 1945. Albuquerque: The University of New Mexico Press, 85.

14. Myrriah Gómez. “Unknowing, Unwilling and Uncompensated: The Effects of the Trinity

Test on New Mexicans and the Potential Benefits of a Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) Amendment,” 17.

https://www.kob.com/kobtvimages/repository/cs/files/TBDC%20HIA%20final%20report%202-8-2017.pdf

15. Szasz, Ferenc Morton. 1984. The Day the Sun Rose Twice: The Story of the Trinity Site Nuclear Explosion, July 16, 1945. Albuquerque: The University of New Mexico Press, 144.

16. Richard L. Miller's Under the Cloud: The Decades of Nuclear Testing (1986), Appendix D p. 473-483.

17. National Cancer Institute. 2020. “National Cancer Institute Cancer Risk Projection Study for the Trinity Nuclear Test Summary of Findings in Health Physics.” https://dceg.cancer.gov/research/how-we-study/exposure-assessment/community-summary#background-on-the-trinity-test

18. This work is being done in partnership with and the support of the Orfalea Center for Global & International Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. The TBDC’s recent testimony to Congress can be seen here: www.youtube.com/embed/9gCGejMaYu4?autoplay=1

19. Readers are encouraged to contact Tularosa Basin Downwinders with questions and or comments. The mission of the TBDC is to bring attention to the negative health effects suffered by the unknowing, unwilling, uncompensated, innocent victims of the first nuclear blast on earth that took place at the Trinity site in South Central New Mexico. Ultimately, the goal is the passage of the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act Amendments to bring much needed health care coverage and compensation to the People of New Mexico who have suffered with the health effects of overexposure to radiation since 1945.

20. Dipka Bhambani. “Trump Administration Pivots to Nuclear Energy, Finds Lever Against China, Russia.” Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/dipkabhambhani/2020/08/07/trump-administration-pivots-to-nuclear-energy-finds-lever-against-china-russia/?sh=f3c647547b15