The Future of Human Rights

archive

The Future of Human Rights

Human rights have fallen on hard times, yet they are needed now more than ever. Despite historic advances in human rights law and mobilization, unprecedented numbers of people suffer war crimes, forced displacement, ethnic persecution, gender violence, and backlash against rights defenders. These hard times in practice are matched by harsh criticism in theory. Nationalists and realists claim human rights demand too much from sovereign states, structuralists and legal skeptics say human rights are not enough to secure social justice, while post-modern, post-colonial, and critical feminists argue that liberal rights are the wrong kind of politics.

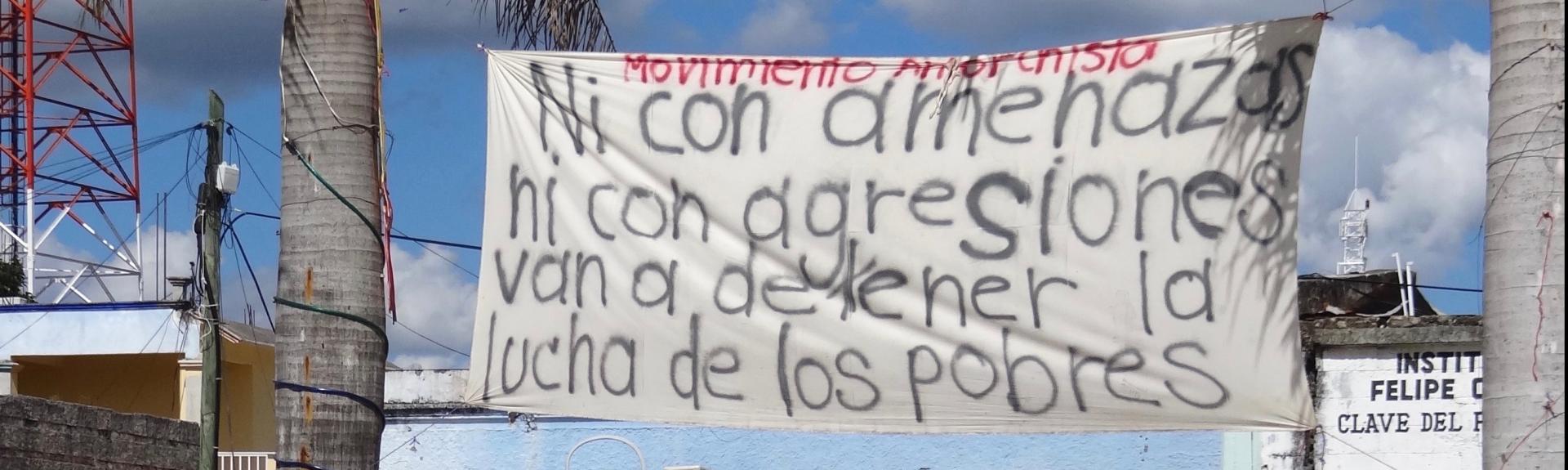

Far from the “end times” of human rights decried by Hopgood and Posner alike, it is time for a reboot that closes historic gaps and confronts emerging challenges. After several generations of measured success and unexpected shortfalls, the future of human rights lies in fostering the dynamic strength of human rights as evolving political practice. People all over the world—from Amazonian villages to Iranian prisons—use human rights to gain recognition, campaign for justice, and save lives. With all of its limitations, human rights have proven to be the most sustainable basis for solidarity in the face of violence and oppression. When human rights are viewed as evolving political practices rather than abstract legal principles, the future of human rights can expand these practices to meet the challenges of persisting and emerging threats to human dignity.

Historically, the exercise of human rights has built unexpected strengths that partly compensate for its genetic flaws and point toward a future course. The legacy of human rights is progressive but narrow and contested: harsh criticisms of human rights as excessive in regard to sovereignty, or as too lean in relation to structural factors, or as too Western, legalistic, and elitist, are leveled by the likes of Hopgood, Moyn, Baxi, and others. Then again, there are many pointers in the direction of rights as political process: in Beitz’ constructivist concept; in Rorty’s pragmatism; in deSousa Santos, for whom contesting rights builds a global ethos; in Goodhart, who proposes a “toolbox” approach, and in Martha Nussbaum’s capabilities orientation. Such examples point beyond the limits of the rights regime’s legalistic origins and prevailing binary logics toward seeing in human rights a unique power to mobilize social change. Unleashing and focusing the dynamism of human rights to expand its limits will have to take account of new actors and a dialectical relationship between levels of global order. Reconstructing human rights in the 21st century will involve expanding rights claims, rights mechanisms, and governance responsibilities.

When human rights are viewed as evolving political practices rather than abstract legal principles, the future of human rights can expand these practices to meet the challenges of persisting and emerging threats to human dignity.

The first task for the future is to deal with the unfinished business of the past. The rights regime was constructed to protect and empower, but protection has fallen under haphazard humanitarian initiatives while the pursuit of civil and political rights is assumed to bring physical security. The international human rights regime did not anticipate the decoupling of war crimes, democratization, fundamental freedoms, and physical integrity. Insecurity persists in post-conflict and democratic environments, undermining the exercise of hard-won freedoms. Stronger safeguards must therefore be crafted. Similarly, the gap between rights and citizenship remains unresolved, with increasing consequences for “people out of place.” As most rights and duties are still linked to citizenship, improving access to justice within states and responsibility to protect across borders comprise lagging tasks for the fulfillment of rights.

migrant children rescued on Mediterranean coast, 2015

While the security gap calls for more rights and the citizenship gap demands more justice, the problem of “private wrongs” requires more governance. Accountability for the increasing range of violations by non-state perpetrators is building the doctrine of “due diligence” to increase state responsibility. Human rights in the private sphere and across borders are promoted through initiatives on gender violence, corporate social responsibility, and multiculturalism. The precarious status of refugees affords numerous examples in which the challenges and potential responses to gaps in protection, citizenship, and security may be traced.

At the level of norms and claims, the leading challenges to the exclusions and bias of human rights norms are actually opportunities to expand the agenda to fulfill the original promise. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that we are “ free and equal in rights and dignity,” yet both pairs of concepts have become unbalanced in the generations that followed. The challenge that legal rights do not address socioeconomic and cultural inequity can be met by increasing the practice of interdependence appeals, solidarity coalitions for issues like labor rights and food, and mutual reconstruction of rights-based development. The challenge of rights and dignity is the key to promoting human rights as a lingua franca in a multicultural world. We can transcend outmoded claims of cultural relativism through fostering the right to identity, the right to participate in inclusive cultural change, and a deeper reading of the struggle against discrimination and the dignity of difference. The experience of indigenous rights campaigns provides instructive cases in which such modes of rights expansion can be modeled.

The future of human rights also requires expanding our understanding of political processes of mobilization and governance. The expanding practice of mobilization has moved to new issues, new actors, and new functions, representing a shift from advocacy to monitoring and implementation. Meanwhile, the international human rights regime has moved beyond legal and top down global institutions to multi-faceted endeavors such as boycotts, rights-based public policy, and multiple layers of governance. Rights are being constructed in new directions that complement the historic international regime. Mobilizations to combat violence against women show new pathways of political process and creative change in global governance.

Human rights are a necessary but not sufficient strategy for improving the human condition. Looking towards the future, human rights proponents must also temper expectations and systematically acknowledge our limitations. Rights can help manage but not substitute for external parameters such as resources and the environment. Rights can help secure a space for the development of identity and empathy, but rights cannot supply meaning, community, or care. Some of the shortfalls of human rights efforts result from inappropriate or unwieldy demands.

The future of human rights rests with all of us, without exception. Human rights are nothing more or less than a political program for the free and equal development of human possibility. The way forward is dialectical, dynamic, and strategic. This is no time to abandon ship—it is a time for all hands on deck to navigate the storm and plot a new course. The future of human rights is to continually construct a practice of global citizenship as the most sustainable basis for solidarity in a troubled world.

Baxi, Upendra. The Future of Human Rights. Second edn. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008.

Beitz, Charles R. The Idea of Human Rights. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2009.

deSousa Santos, Boaventura and César A. Rodriguez-Garavito, eds. Law and

Goodhart, Michael. Human Rights: Politics and Practice. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2009.

Hopgood, Stephen. The Endtimes of Human Rights. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2013.

Moyn, Samuel. The Last Utopia: Human Rights in History. Cambridge, MA:

Nussbaum, Martha C. “Capabilities and Human Rights.” Fordham Law Review 66 (2),

Posner, Eric. The Twilight of Human Rights Law. Oxford and New York: Oxford

Risse, Thomas, Stephen C. Ropp, and Kathryn Sikkink, eds. The Power of Human Rights:

Cambridge UP, 1999.

Rorty, Richard. Contingency, Irony and Solidarity. New York: Cambridge UP, 1989.