Ambedkar and Du Bois on Pursuing Rights Protections Globally

archive

Ambedkar and Du Bois on Pursuing Rights Protections Globally

Therefore, Peoples of the World, we American Negroes appeal to you … No nation is so great that the world can afford to let it continue to be deliberately unjust, cruel and unfair toward its own citizens.

The world owes a duty to the Untouchables as it does to all suppressed people to break their shackles and to set them free.

In this era of populism and ethno-religious tribalism, when battles for some of the most basic principles of rights and social equality must seemingly be re-fought daily, it may feel as though there is little time or energy left to consider issues of global justice, much less global institutional development. It also may appear that any dialogue on the global has been rendered moot in the current context, where for example far-right supporters of the US president deploy the term ‘globalist’ as a slur against advocates of even a moderate liberal internationalism.

Yet some of the most prominent historic champions of those most basic principles of equality and rights have looked beyond the state for support in promoting them within. In so doing, they have indicated an important global institutional imaginary—a multi-level set of political institutions capable of promoting individual rights protections domestically, and of giving those facing domestic repression some meaningful place to turn. Such an imaginary is well worth upholding as an alternative vision of political institutions and it can be of practical use in guiding some current political struggles.

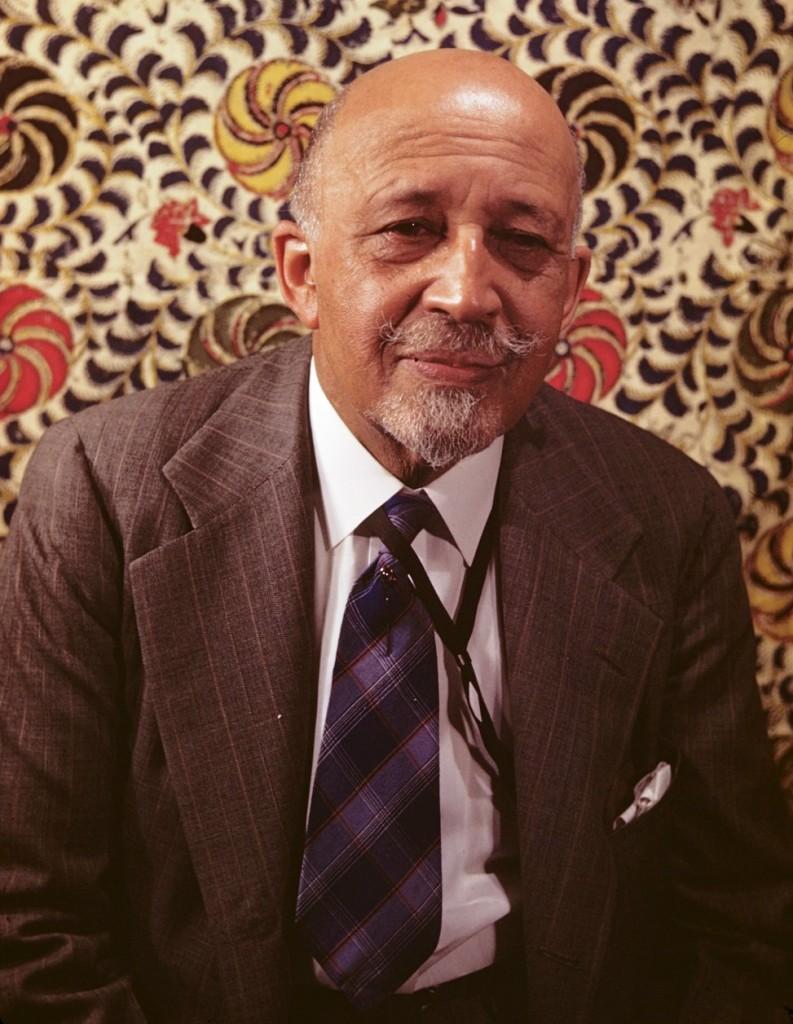

B.R. Ambedkar and W.E.B. Du Bois are both renowned as campaigners for domestic equality, and indeed as significant social and political thinkers in their own right. Ambedkar was in fact the first Dalit to earn a doctoral degree, from Columbia University in 1927. Du Bois had been the first African-American to earn a PhD from Harvard, in 1895. Ambedkar, best known as the tireless advocate for India’s Dalits (formerly ‘untouchables’), went on to serve as chief architect of the country’s post-independence 1950 Constitution, which established a range of individual rights protections. Du Bois, as a co-founder of and leading figure for decades in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), similarly challenged the pervasive exclusion and domination of African-Americans. Both demanded a wholesale transformation of their deeply hierarchical societies.

Both also offered blueprints for political institutions beyond the state that would be capable of hearing and addressing challenges to repression within. Du Bois sought to put his plan into practice at the newly formed United Nations in the mid-1940s, and Ambedkar helped to inspire a current network of Dalit activists to do the same. Du Bois and the NAACP delivered their ‘Appeal to the World’ to the UN in 1947. This included exhaustive documentation of racially motivated discrimination and violence against African-Americans. In drafting the Appeal’s introduction, Du Bois highlighted the vast gulf between America’s founding ideals of equality and the treatment it had given to African-Americans: “a great nation, which today ought to be in the forefront of the march toward peace and democracy, finds itself continuously making common cause with race hate, prejudiced exploitation and oppression of the common man.” He called on the UN and its member countries to pressure the United States to take more decisive action against such discrimination as “a basic problem of humanity.”

W.E.B. Du Bois (photo: Van Vechten Collection, Yale)

The effort was strongly resisted by the US government, which had long been suspicious of Du Bois’ activities and had put him under surveillance from the early part of the century. The highly visible UN petition in fact gave such foes as the Soviet Union evidence to use in denouncing the US as hypocritical in its global promotion of freedom and rights—something that brought Eleanor Roosevelt to the brink of resigning from the NAACP Board. The Appeal, however, also highlighted an alternative model of political struggle. This was a model where rights claims against a state would not be decided solely by that state. Rather, governments would, in Ambedkar’s phrasing, have to answer for their actions “before the bar of the world.”

Ambedkar was inspired by Du Bois’ efforts and shared his aspirations. He had indicated the alternative model as early as a 1930 speech in which he noted that a right of appeal to the League of Nations had been granted to some vulnerable minorities within central and eastern European countries created after World War I. Such rights of global appeal “would be a very desirable addition to the armoury of the Depressed Classes,” he said, though he did not place any strong hope in the possibility that the League or other authorities would actually offer effective aid to those facing repression.

some of the most prominent historic champions of [the] most basic principles of equality and rights have looked beyond the state for support in promoting them within.

Ambedkar was more hopeful about the United Nations, and he wrote to Du Bois asking for a copy of the NAACP petition. Ambedkar noted some regret later, in his 1951 speech of resignation as India’s Law Minister, that he had ultimately decided not to approach the UN himself, but to place his faith in the new Constitution: “I had prepared a report on the condition of the Scheduled Castes [Dalits] for submission to the United Nations. But I did not submit it. I felt that it would be better to wait until the Constituent Assembly and the future Parliament was given a chance to deal with the matter.… What is the [condition of] Scheduled Castes today? So far as I see, it is the same as before. The same old tyranny, the same old oppression, the same old discrimination which existed before, exists now, and perhaps in a worse form.”3

B. R. Ambedkar

Ambedkar died in 1956. Some four decades later, a network of Dalit activists inspired by him both adopted and extended the international outreach blueprint he had indicated. The National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights (NCDHR) was formed to put Dalit rights groups around the country in coalition, and to press the Indian government for action from below and from above. The global outreach has involved lobbying UN human rights bodies as well as the European Parliament, US Congress, and others actors for support in challenging ongoing caste discrimination. Partly as a result of those outreach efforts, UN bodies have affirmed that caste discrimination is covered by the Convention. Successive Indian governments have resisted such a finding, however, while also resisting international scrutiny of such domestic issues.

The current government, led by the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party, has effectively barred vital overseas funding for thousands of non-governmental organizations, including numerous ones in the NCDHR network. BJP officials contended in interviews that the Dalit activists are acting primarily as disloyal citizens, airing India’s domestic challenges on a global stage. Their claims echo the accusations of disloyal or even treasonous behavior made against both Ambedkar and Du Bois in their time.4

Ambedkar was inspired by Du Bois’s efforts and shared his aspirations.

Overall, the NCDHR network has succeeded in bringing global attention to caste discrimination, and putting greater pressure on the Indian government. The resistance, scrutiny, and recrimination faced by activists, however, highlights the power states and their governments continue to wield as judges and enforcers in cases involving claims against them. It also highlights some deep, systemic challenges to addressing rights rejections in the current global system.

There is much more to be said about the alternative indicated by Du Bois, Ambedkar and the NCDHR activists, which I am detailing in a forthcoming book.5 It would be a system in which states, or their ruling governments, would not be the final judges in their own cases when it comes to claims of discrimination, unequal treatment and broader rights rejections. Individuals would have various mechanisms of challenge, and of making domestic repression more visible on the global stage. The current European Union represents a partial model. Or, better, it is a laboratory where struggles over institutional models have been playing out—one where some rights-based challenges can be lodged by individuals, and where state governments continue to try to exert dominant influence.

NAACP protestors in Lansing, Michigan demand action on the water crisis in Flint, 2016. (Source: WEYI News)

Ambedkar and Du Bois in some ways imply a more ambitious model, in which fully global institutions would play significant roles in the oversight of states’ rights records, and in which they would have some substantive powers to address widespread violations. We remain some distance from the latter especially, and there is no suggestion here that a genuinely rights-respecting and rights-protective ‘world government’ is impending or could be realized in the near or medium term. The alternative global imaginary gives important guidance, however, for current efforts. As the American Civil Liberties Union has recently suggested, in highlighting Du Bois’ actions as a model for promoting civil rights, the alternative can direct our attention to existing mechanisms for oversight of states by a neutral global arbiter.6 Those currently engaged in battles to protect very basic rights to equality and against discrimination can make use of UN assessments of states’ human rights records in their own struggles, as indeed the Dalit activists have repeatedly done. In so doing, they make meaningful use of the features of a global institutional alternative which have emerged, while also affirming broader aspirations for change and helping to make them more prominent as part of a global imaginary, one that embraces a vision of political possibility beyond the state.

1. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, ‘An Appeal to the World’ (1947). Online: http://www.blackpast.org/1947-w-e-b-Du Bois-appeal-world-statement-denial-human-rights-minorities-case-citizens-n

2. Ambedkar, B.R., in Vasant Moon (ed.), Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches, Vol. 9 (Bombay: Education Department, 1991[1943]), 389-435, at 397-98: https://www.mea.gov.in/Images/attach/amb/Volume_09.pdf

3. Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches, 14:2, 1317-27: http://mea.gov.in/Images/attach/amb/Volume_14_02.pdf

4. The author interviewed 26 mid- and senior-level BJP officials and elected representatives, as well as more than 50 NCDHR activists, persons they serve and caste-issue experts in India from 2010-2016.

5. Luis Cabrera, The Humble Cosmopolitan: Rights, Diversity, and Trans-State Democracy (Oxford University Press, forthcoming 2018).

6. American Civil Liberties Union: https://www.aclu.org/news/70-years-after-web-du-bois-appeal-un-groups-press-us-racial-equality