Mongol Hordes, the Khmer Rouge, and the Islamic State: Non-Modern Conceptions of Space and Time

archive

Mongol Hordes, the Khmer Rouge, and the Islamic State: Non-Modern Conceptions of Space and Time

Most scholarship and journalism about the Islamic State fail to grasp the true meanings of the group’s unorthodox relationship to space and time. The group’s orientation to territory and temporality is different from normative Western models both tactically and the ideologically. That is, the Islamic State, when operating at its ideal capacity, traverses time and space. It is both any-where and every-when.

This means that the way we approach the group might benefit from a kind of reorientation. The Islamic State is not just a nation-state-building enterprise and it is not a guerilla terror group. Instead, it sometimes one, sometimes the other, and sometimes both. It is more diffuse, nimble, and protean—by nature and design—than conventional modern nation-states. Our models need to account for these differences.

One way to re-think and re-conceive the Islamic State is to use models that are either outside of or at least in opposition to Western frames. This essay does that by pairing the Islamic State with two conceptual forerunners: the Mongol Hordes of the Thirteenth Century and the revolutionary Khmer Rouge regime that seized power in Cambodia in 1975. The Mongols are relevant because the group operated in a non-Westphalian context where national boundaries meant little. The same is true of the Islamic State. Additionally, their modular approach to statecraft was not unlike the contemporary decentralized organization of the Islamic State, where national borders are blurred and troubled by strategic and technological innovation. The Khmer Rouge is a more contemporary case, pertinent due to “Year Zero,” a politically motivated reset of the national calendar and rejection of Western history. Both the Khmers and the Islamic State reorient themselves and their subjects to an altered sense of temporality that is strategically anti-modern and anti-Western. Their work against normative time is symbolic of a disorientation process in the service of their apocalyptic aims.

Flexible Borders and Fungible Citizens: The Case of the Mongols

The most significant period of Mongol power in Asia began in 1206 with the ascendancy of Chinggis Khan, who united a set of disparate, warring factions and formed the Golden Horde that conquered much of the continent during the time of Chinggis and his subsequent progeny. The Mongols were a mobile war-making apparatus; they never sought to build the stable cities of their Greco-Roman forebears. Instead their strategies and objectives were always being refashioned according to what was needed for success in battle, so that, for example, hunting for food doubled as military training.

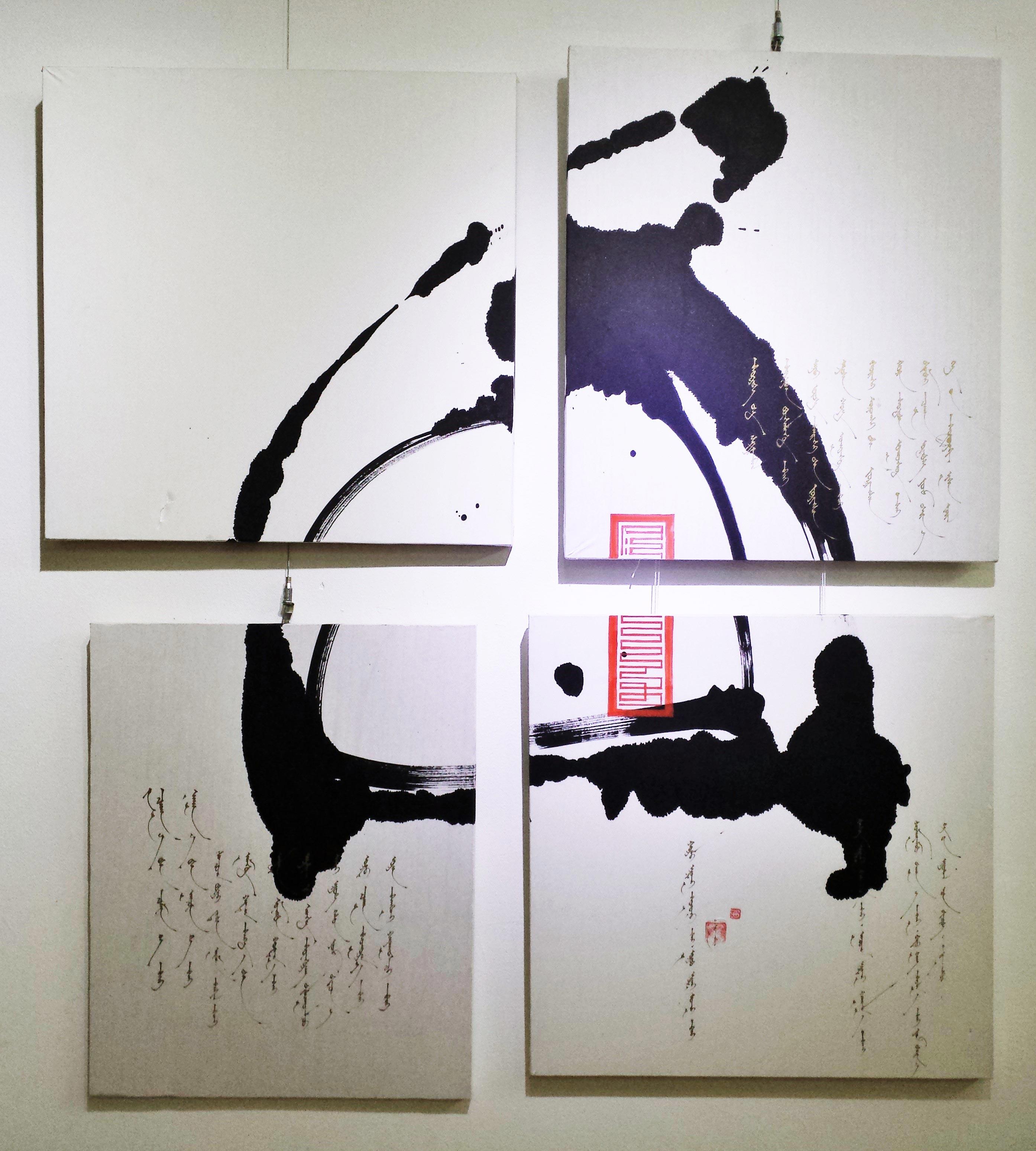

Mongolian calligraphy - Wikimedia Commons, A. Orkhon

This modular approach extended into statecraft—there was little that was discernibly “Mongol” within the group’s larger structure. While the group was known for their brutality in wartime, in many cases, they allowed conquered groups to maintain many of their customs, traditions, and organizational structures, as long as they could be re-made to serve their new masters. The group’s language, government structure, and religious practice were all either drawn from their recently conquered subjects or constructed whole-cloth to serve the war effort. Even the term “Mongol” itself may be most productively understood as a modern depiction of a social order in which citizenship was fluid, not designated by the kind of nation-state frame we use today.

The Islamic State employs a similarly malleable strategy. The “Islamic State’s decision-making is opportunistic, adaptive, and dependent upon its leaderships’ [sic] shifting propensity to implement its ideology,” one analyst, Craig Noyes, writes, suggesting that the group, which purports to embrace the doctrinally rigid Jihadi-Salafist sect, is actually more adaptable than it tries to appear. “[I]t is only when Islamic State has adequate governing strength, or a decision cannot provide short-term organizational benefit, or IS’s ideological legitimacy and grand strategy are at stake that it pivots to overtly ideological decision-making.”1 The Islamic State has collaborated with non-Islamist groups for tactical maneuvers and propaganda purposes, all in the service of war-making.

The Islamic State… is more diffuse, nimble, and protean—by nature and design—than conventional modern nation-states. Our models need to account for these differences.

Moreover, the Islamic State and the Mongols both used technological innovation rather than lines on a map to expand their territory in multiple places at the same time. The Yam, a set of roadways developed in 1234 by Chinggis’s youngest son, Tolui, gave the empire its shape—anywhere the Yam went was a station of the empire. The Internet might be called the Islamic State’s Yam—a space of flows where the aims and subjective reality of Islamic statehood is realized not at its interstices but at its networked nodes. Each computer connected to Twitter and spamming hashtags, sharing beheading videos, or pledging allegiance to the caliphate might be called territory of the Islamic State, which holds the potential to expand far beyond what is understood by contemporary conceptions of nation and nation-state.

Year Zero and the Rejection of Modern Time

The Islamic State also attacks and disrupts mainstream notions of time and the temporal. So, too, did the Khmer Rouge, a rebel Cambodian cabal led by the despot Pol Pot, who seized control of the capital city of Phnom Penh on April 17, 1975 and declared “Year Zero,” a reset of time, history, and the outside world. The Khmer Rouge platform was built on an oversimplification of history that laid blame for the nation’s struggles at the feet of its Western colonizers; by re-setting the clock, the revolutionaries contended that they could throw off the organizing system of their foreign oppressors. All holidays more than seventeen years old were forgotten; all schools were closed; most intellectuals were killed. The goal was to reconstruct each individual, atomized citizen from the ground up, convincing them that they inhabited a time before colonial oppression, when the great Twelfth-Century city of Angkor Wat—the nation’s apogee—was more than a ruinous reminder of a glorious past.

Khmer Rouge leaders sit in a train car in 1975; Pol Pot is on the far left.

The Islamic State’s relationship to time is similarly political and complex. It, too, employs a set of rhetorical techniques that effectively reorganize time by constructing an ideology from various hadith (records) of the Prophet Muhammad from diverse sources, regions, and time periods.2 “Modern” is a pejorative term within the group, Gregorian (Miladi) dating is rejected in favor of the Islamic lunar calendar, and the Islamic State seeks to operate every-when—existing outside of the linear telos of the “modern” west and putting various contexts to use in the service of its work.

This study is not intended to be overly ambitious. Neither of the cases examined here could ever stand as a strict one-to-one comparison. Instead, what these conceptual antecedents allow us to do is to reorient our thinking about the Islamic State. Perhaps scholars and policymakers have spilled so much ink debating what the Islamic State “is” because “what” it “is” is complicated by its flexibility in time and space. This happens in large part because too much of our understanding, strategy, rhetoric, and policy-making is limited by a Western orientation to a non-Western conception. As Edward Said reminds us, “[D]iscussions of the Orient or of the Arabs and Islam are fundamentally premised upon a fiction.”3 The fiction, his work would illustrate, was an Orientalizing one, where the Orient was conceived within Western/Occidental epistemological frames as pre-modern, backward, and unsophisticated. From that inaccurate and presumptively superior position, normative cultural understandings have taken hold in many Western contexts. The Islamic State in fact has its own context, and the time- and space-shifting of the group are products of its alterity as much as they are strategies that advance the group’s intentions.

the Islamic State seeks to operate every-when—existing outside of the linear telos of the “modern” west...

If the Islamic State can “exist” anywhere one of its adherents is Tweeting, then we need a new conception of what a state is that takes into account its networked and dispersed “citizenry.” If the Islamic State can “exist” at any time, then a more robust historiographical analysis of its references might prepare us for what might come next.

Drawing upon alternative epistemology is a way to emphasize the exteriority of the subject. Changing the orientation of our research upsets facile assumptions about the group, reframing the study outside of an Occident/Orient dichotomy. These cases help us to tap different wells in order to generate knowledge from alternative contexts and connective themes. Rather than getting bogged down in any of the ongoing debates around the Islamic State, this essay suggests attempts to generate new paradigms for understanding it, drawing from these intersections to create new pathways for understanding across time and space.

___________

The author would like to dedicate this work to the memory of David Giovacchini.

1. Craig Noyes, “Pragmatic Takfiris: Organizational Prioritization Along Islamic State’s Ideological Threshold” Small Wars Journal (July 26, 2016). Accessed May 12, 2017. http://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/pragmatic-takfiris-organizational-prioritization-along-islamic-state%E2%80%99s-ideological-threshol.

2. Graeme Wood, “What ISIS Really Wants.” The Atlantic (2015) Accessed May 15, 2017. http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2015/03/what-isis-really-wan....

3. Edward W. Said, “Islam Through Western Eyes,” The Nation. (April 26, 1980). Accessed online May 17, 2017. https://www.thenation.com/article/islam-through-western-eyes/.

Cras ultricies ligula sed magna dictum porta. Cras ultricies ligula sed magna dictum porta.Cras ultricies ligula sed magna dictum porta. Cras ultricies ligula sed magna dictum porta.Cras ultricies ligula sed magna dictum porta.